More evidence from the food front that macro-shifts in consumer choices/awareness are persuading companies to reconsider their products–and the future of food:

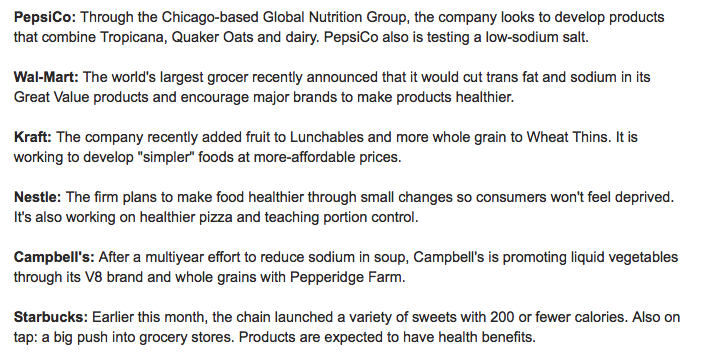

This summary comes from a recent Chicago Tribune article outlining the manifold effects the food movement has had on behemoth corporations. Major players like Wal-Mart (largest food purchaser in the country), Kraft, and PepsiCo are scrambling to figure out how to twist fundamentally unhealthy products into “healthier options.”

To be more accurate, though, I should say that this is an effort to further twist fundamentally unhealthy products into something they can’t be. We’ve been seeing great changes over the past several years: “Made with Whole Grain” now adorns cereal boxes from the top shelves (“adult” cereals) to the bottom (where the kiddies look); RbGH-milk is in significant decline; and “low-sodium” banners are proliferating across labels. While the food is being tweaked, the accompanying advertisements are being amplified to a much greater extent. “Change it a little and promote the hell out of it” has long been an approach of the food industry. But of course, “just because a processed food is a little bit less bad than it used to be,” as the always-enjoyable Marion Nestle words it, [it] doesn’t necessarily make it a good choice.”

Hobbyist rhetoricians might take pleasure in tracking a few threads in the food arena:

1) The obvious: changes in a food labeling. Make it a game with your family and friends! Award points based on a ratio between how brazenly stupid a phrase/picture is and its potential persuasiveness. So for instance, “Picked Fresh!” would receive 20pts, while “Naturally Cut” could get up to 40pts, depending on the product. When you find produce being declared “Cholesterol Free” then you’ve hit the jackpot! Give yourself 100pts! If you spot “Locally Known” then you’ve won the game: 1,000pts. (Points may be redeemed for candy-bars and/or plastic trinkets.)

500 points!

2) The less obvious: changes in food placement. The layout of a supermarket is rhetorically designed, with staples such as dairy, bread, and meat often occupying the back corners. Walk the periphery of a store and you’ll most likely find all the good stuff you need. Walk through any of the numerous aisles in between and you’ll be confronted with staggering variations of corn and soy. Chips and soda are located in the same aisle: while supermarkets very rarely make a profit off of soda, the percentage markup on chips easily makes up for it. They know the salty goes with the sweet.

Though supermarket(er)s have known the appeal of placement for some time, the technics of it are going through a period of increased research scrutiny, with psychologists getting in on the game. Thankfully, proponents and marketers of healthy foods are discovering that savvy rhetorical strategies are just as applicable to their product as those that push junk. NPR recently reported that grocery stores are shining a new light on healthy foods–quite literally:

Take product placement and soft, focused lighting, for example. Items that are highlighted in this way — even if they aren’t on sale — sell about 30 percent more, Wansink [author of Mindless Eating] says. They just look more appealing than products under harsh, overhead fluorescent lights.

One area where the rhetoric of food placement is getting a lot of attention is in the cafeteria. I highly recommend you check out this interactive piece published by the New York Times that outlines how the lunch line is being redesigned to highlight healthier foods. In one research report, the simple act of putting fruit in an attractive fruit bowl rather than the usual stainless steel bowl more than doubled the amount of fruit sales. Putting the chocolate milk behind the regular milk (instead of beside) greatly reduced its selection.

Keep your eye out for how stores are shifting food placement to affect choice, regardless of whether it’s for the good or bad.

3) Time traveling through analogy: Big Food as Big Tabacco. I’m beginning to see a lot more parallels being made between where Big Food is at right now with where Big Tabacco was at in the late ’80s and early ’90s, in the ramp up to the Master Settlement Agreement. Tabacco companies got sued in an effort to recoup health care costs dumped on states. We could see the exact same discussion about food taking place over the next few years, as more evidence arises that links our cheap food with high health care costs. And just as Tabacco sought frantically for many years to discredit information that linked it to cancer, the Producers of Processed will work to undermine similar science that does little else than simply confirm common sense. In the meantime, we can enjoy a variety of mind-spinning industrial concoctions that purport to have our best interests in mind; “lite-sugar” products are the equivalent of ultra-lite cigarettes.

I’ll be interested to hear from any rhetoricians out there where they’re seeing these elements and how they’re being leveraged. Send word to Harlot in a savvy article and we’ll work to get it published, yo.

When he buys an item of food, consumes it, or serves it, modern man does not manipulate a simple object in a purely transitive fashion; this item of food sums up and transmits a situation; it constitutes an information; it signifies.

~ Roland Barthes