Emoji, Emoji, What for Art Thou?

Lisa Lebduska

By providing a history and context for emojis, this essay argues that they are more a means of creative graphic expression than a threat to alphabetic literacy, and that their study contributes to a re-materilaizing of literacy. The essay acknowledges that in some instances emojis do help to clarify the intent or tone of alphabetic writing, but emojis, like alphabetic writing, are culturally and contextually bound. Emojis expand expression and in doing so open themselves to re-appropriation, interpretation and even misinterpretation, along with the affirming possibilities of artistic creation.

"We were just nerds, goofing around" (Fahlman qtd. in Garber). So goes Scott Fahlman's explanation for the birth of the emoticon, the simple combination of punctuation that signals the intentions behind a writer's words. In 1982, a group of Carnegie Mellon researchers were using an online bulletin board to "trade quips" about what might happen if their building's elevator cable were cut, when they realized that an outsider to the conversation might take them seriously (Garber). They developed the iconic :) to make sure everyone else was in on the joke. And the rest, as the saying goes, was history. Or were the emoticons word-devil spawn? Did they constitute an attack on language, yet another instance of the "erasure of language" (MacDonald) what James Billington, the Librarian of Congress, described as "the slow destruction of the basic unit of human thought — the sentence" (qtd. in Dillon)?

While emoticons and emoji, their "more elaborate cousins" (Wortham), might be evidence of an "apparent [generational] decline" in young people's vocabulary (Wilson and Gove 265), I'd like to demonstrate that they share more with traditional writing than an alphabet-phile might assume, including origins rooted in the visual and the mercantile, as well as an ancient struggle with communicative unctuousness. Emojis are not so much destroying linguistic traditions as they are stretching them, opening a gateway to a non-discursive language of new possibility and even responding to John Trimbur's call for a rematerializing of literacy (263), by reminding us that writing always had and always will have a visual component mediated by a material world. The narratives of emojis, then, are the narratives of writing itself.

Scholars have called out the myth of alphabetic literacy's transparency as a denial of writing's materiality and the role played by larger systems of production (Trimbur), as well as an assertion of Western superiority (Miller and Lupton). In response to this need to materialize writing, I wish to provide context for emojis, complicating these tiny stamps of humanity and unpacking some of the alphabetic resistances to them so as to position them as an emerging visual language of play, whose study will help us to think more visually and materially about writing and encourage us to experiment with the ludic potentiality of a non-discursive form.

Almost a decade after the Carnegie Mellon invention of emoticons, emojis (translated as "picture characters") emerged in Japan, consisting of both more fleshed-out versions of emoticons (☺ instead of :) for example), as well as a pantheon of objects, activities, and events ranging from cactuses to cash. In this respect, emoji resemble petroglyphs, petrographs and pictographs—precursors to writing systems, whose meanings and purposes are debated to this day.

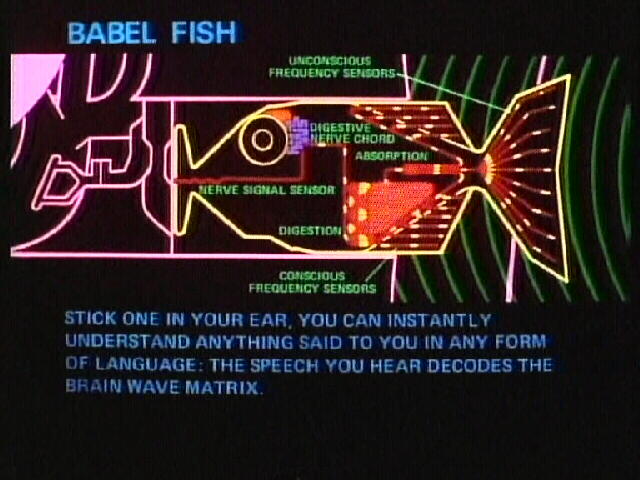

Emoji origins in teen and commercial culture are indisputable. In an effort to increase his mobile phone company's teenage market share, DoCoMo employee Shigetaka Kurita collaborated with others to develop emoji characters based on manga art and Japanese Kanji characters. But senders and recipients had to use the same network in order for the characters to display properly (Marsden). Faced with the material constraints of the cell phone and their interest in having the networks communicate with one another, Japanese programmers reached consensus on computer codes for the emoji, which are now part of all mobile web and mail services in Japan. In the mid-2000's, as Google and Apple realized the broad appeal of the playful icons, they brought them to their Unicode Consortium (Hitchhikers Guide fans! Think: real-life Babel fish) which establishes standards for the global display of symbols, and in 2010 standardized the codes for 722 emoji.

This move to standardize resembled the efforts of Louis the XIV to standardize typographic forms through the commissioning of the "roman du roi" typeface, which relied on an Academy of Sciences committee to map the typeface onto a grid, as opposed to previous typefaces which had evolved over time and which were hand cut. Trimbur sees the Sun King's commissioning of the committee as an attempt "to embody the authority of the scientific method and bureaucratic power" (266). Individual engravers would no longer have an influence on the emerging shapes and the sameness of every printed letter would be guaranteed through its adherence to a mathematically reproducible template. Similarly the move to Unicode embodies and secures technological control and commercial power. On the one hand the use of a uniform code ensures that what senders send is what recipients see, but senders and users must both have the hardware (usually a smartphone, though emojis can be displayed on email) as well as access to an emoji keyboard if they wish to send. Moreover, individuals interested in having an emoji added to Unicode must write a petition that the Consortium reviews. Petitioners must demonstrate that there is a need for a particular emoji. According to Mark Davis, president of the Unicode Consortium, the emoji "must be in the wild already" (qtd. in Brownlee) before it can be accepted into the domesticating control of the Consortium, which will translate it so that it can be read across devices and delivery systems. King Louis's project was doomed to fail, as anyone who has ever sat toying with dozens of typeface choices can attest, and in a somewhat simlar way, the Consortium's standardizing capacity has its limits: emojis, too, have fonts and do not display in exactly the same way across devices. Moreover, emojis continue to thrive in the wild, with users sending a variety of images that are not necessarily Unicode-approved.

Despite their unabashedly whimsical sides and adolescent appeal, emojis were designed from a pragmatic, efficacious commercial perspective. Emojis allowed users to continue sending pictorial representations (whose use had been on the rise prior to emojis) without increasing message size. Bandwidth did not need to increase and speed was maintained as each emoji counted as only a single character. Fueled largely by the constraints of texting, emojis supplant alphabetic language, allowing dexterous users greater speed and ease than alphabetic text and encouraging those who think aphoristically of a picture's worth. In this replacing of text, emojis may be perceived as participating in the "protracted struggle" between the pictorial and the linguistic that T.J. Mitchell observed, "the relationship of subversion, in which language or imagery looks into its own heart and finds lurking there its opposite number" (43). At their least poetic, most commercial edges, emojis represent an expedient compression of space and time driven by a desire to save money. They were born of a need to conserve space, which translated into time, both of which were expressed in terms of material value. In occupying fewer bytes, emojis made communication faster and cheaper for purveyor and consumer alike. And for this they got a bad rap.

Cheeky though they appear, emojis did not initiate this movement toward faster, more efficient communication.

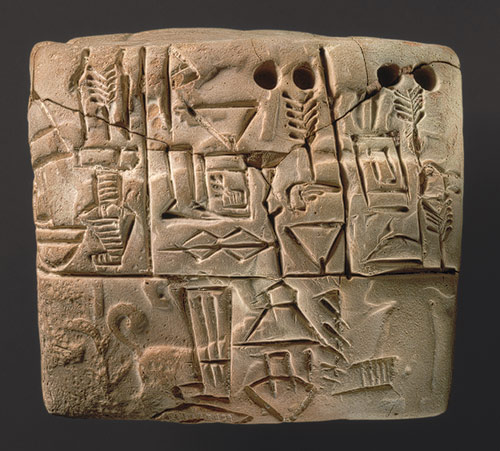

Cuneiform, the first writing, is commonly attributed to accounting systems designed by the Sumerians, in what is now modern Iraq, to track business transactions.

We can imagine ancient poets and priests, even before Plato's famous Phaedrus invective against the memory-dissolving threat of writing, turning away in disdain from early cuneiform and its mercenary mission and what Craig Stroupe describes as a presumed "rhetorical instrumentalism" (629). In the modern era, industry routinely races for faster communication—consider technologies such as the telegraph or the many shorthand systems, which, BTW, is how emojis often are described. All communications—visual and alphabetic—serves multiple purposes, which are sometimes derailed purposefully, through re-appropriation and re-design and re-imagination, and sometimes derailed by accident, happenstance and the emergence of new forms.

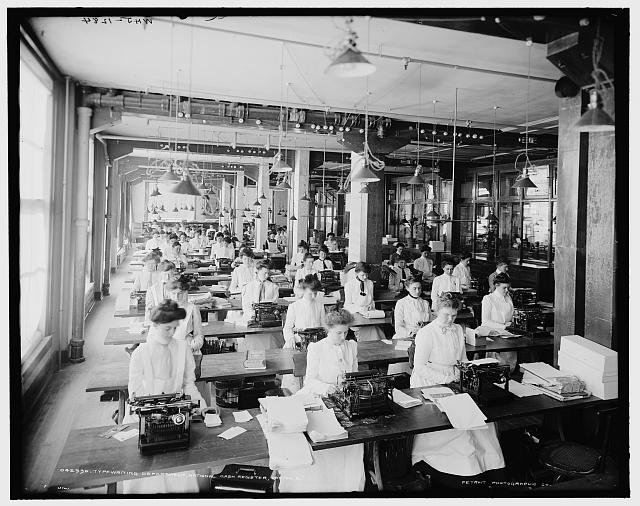

Few of us now would recognize Sir Isaac Pitman's shorthand notation system of 1837:

In their heydays, Pitman's approach and other shorthand systems such as Gregg's were understood by a small subset of professionals who had the proper training in them. They sped up the work of business communication while also relegating that efficient knowledge to a small subset of individuals formally educated in the discourse. Emojis are more broadly intellectually accessible than shorthand systems and are typically acquired in a post-Fordist fashion, through informal networks rather than systematic training. Only readers trained in Pitman notation would recognize the system's lines and squiggles; by contrast, readers without formal emoji training would recognize ☺. I will return to this issue of recognition and iconicity momentarily.

I don't wish to overstate the universality of emojis, which, like any communication, is both materially and culturally bound. Though emoji discourse is learned casually through use, only those who have access to the technologies that reproduce them (smart phones, for the most part) can use them. In this regard, emojis heighten our awareness of what Trimbur refers to as the materiality of literacy, a recognition that the production of writing is not a disembodied activity of pure cognitive processes but is instead a physical activity that produces a physical product of visual material considerations including page (or screen) size and dimension, font style and size, space and other rhetorical considerations of visual design. Trimbur emphasizes the role of typography in reifying this materiality and links it to rhetoric's fifth canon, delivery (263). As with a consideration of typography, a consideration of emoji encourages us to re-visualize writing and to think about how it is circulated, how it performs work in a world of class, race, gender, cultural and age relations.

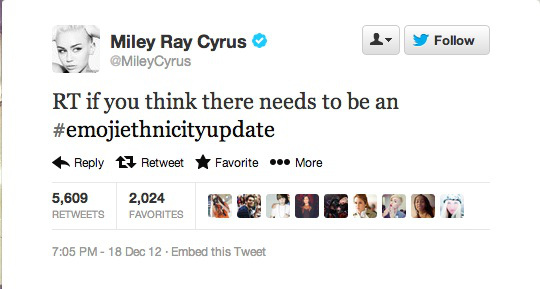

Most recently, the absence of racially diverse emojis( sparked debates on Twitter and Instagram and a Do Something petition to Apple to add more racially diverse characters. The Apple keyboard, as the BBC reported, had numerous white faces and "only two that appeared to be Asian" and none that were black (Kelion). The call for more diverse emoji was dismissed by some in the blogosphere, particularly when Miley Cyrus attempted a Twitter campaign to increase emoji diversity, but at the core of the debate was the construction of race by one of the fastest-growing modes of communication. White again was being represented as a universal, non-raced race. Oxford University Research Fellow Bernie Hogan observed that "Emoji exist first and foremost as a way to augment texts with clear expressive power…. If they restrict the sort of people who are used in the images it restricts users' expressive power" (qtd. in Kelion). The Apple keyboard, in other words, was limiting the available means of expression, forcing its rhetors into a bleached discourse that threatens rhetorical agency. Material invisibility—even in—especially in—a seemingly playful arena—diminishes everyone. Whether they were persuaded by the racial ethos of the petition or more inspired by the fact that 92% of African Americans own a cell phone and 56% own a smart phone (Smith), (constituting a powerful consumer base), is impossible to say, but Apple management has pledged to racially diversify its emoji options. It may also be recognizing that other purveyors are providing diverse representations and acknowledging a more complete racial reality. Oju, an African company aimed at "liberating Africans from digital exclusion" has developed an ojus app for Google, using the tagline "everyone smiles in the same language" and featuring brown-toned faces (Ouja Africa). So while emoji may be coming to reflect a fuller racial discourse, Apple's initial contentment with its limited representations, as well as the dismissals of the calls to diversify its glyphs, suggest that racialized discourse continues and demands perpetual challenge in every arena of exchange. Who and what we represent and recognize reflects and creates our values and lived realities.

Small though they may be, emojis resonate with populist power: Over 300 million images are shared daily by Facebook users; 45 million are posted through Instagram (Rock). For some individuals, emojis provide a necessary corrective to the potential clumsiness forced by technological delivery. Japanese author Motoko Tamamuro explains that the Japanese "tend to imply things instead of explicitly expressing them, so reading the situation and sensing the mood are very important. We take extra care to consider other people's feelings when writing correspondence, and that's why emoji became so useful in email and text – to introduce more feeling into a brevitised form of communication" (qtd. in Marsden). Tamamuro's concerns are similar to those early English-language adopters of emoticons—wary of language's missteps and interested in closing as many gaps between intended and received communication.

Emojis, like the earlier emoticons, sometimes are aimed at helping readers to interpret all the kinds of language that linguist John Haiman categorizes as "un-plain speaking," including sarcasm, "simple politeness, hints, understatements, euphemisms, code, sententiousness, gobbledygook, posturing, bantering jocularity, affectation and ritual or phatic language." Emojis are an attempt to insure that the message we intend is the message that is received, that we can shore up the fissures, the lacuna, the gaps, disconnects, discordances and plain old misunderstandings that inevitably emerge when one brain tries to externalize its thoughts for another through words. Emojis inherit a long tradition of enlisting visuality to do so.

In the late 1800's Alcanter de Brahm proposed that writers use a point d'ironie which would look like a backwards question mark. I sent this trivia to a colleague in the French department, who noted, with his own ironic and somewhat repulsed tone, "The whole point of irony is that it is not pointed out." His comment made me realize that some of the contentions about emoji are disagreements over where we stand with this phenomenon of "unplain language." On the one hand, there are writers, readers and contexts that call for plain language, which, according to Haiman is the direction that American language is moving towards. Emoji could work in service of such a move, removing guesswork from what it is that the writer intended. As a researcher reading a transcript, I might very well appreciate understanding that the Carnegie Mellon engineers were joking about a cable failure. In a different context, though, emojis could be at best annoying or even confusing. If I am in a crowded theater when a fire erupts, I do not wish to look up and see a sign that says, "EXIT ☺" or even "EXIT ☹." I feel the same way about the happy and sad smile faces that adorned my Rhode Island tax return, though I imagine the person who composed it assumed taxpayers might be charmed to see ☹ after "you owe this amount." Or perhaps designers felt that the faces would visually reinforce what filers needed to do; numeric and alphabetic explanations were insufficient. When I filed and saw the ☹ telling me that I owed money, the glyph neither clarified nor charmed; it simply sat as unappreciated adornment whose sad face served up a visual poke in the eye. Like most readers, I inhabit multiple interpretive contexts. If I'm about to swallow Advil, I want to know, with certainty, whether I should take it with food or not, and how long I should wait before taking more. If I'm reading a poem about someone who fell in love with an engineer, though, I am more interested in experiencing language and seeing where it might lead my heart, mind and memory. I take my emojis the same way.

Emojis occupy a both/and position. It is most likely that emojis—as with all attempts to stabilize—result in some magnanimous efforts producing both magnificent failures and stunning successes. So while some composers use emojis to clarify, others use them to mystify and neither necessarily succeeds all the time, because, at the end of the day, humans are what they are: wonderfully complex, connected and individuated creatures, forever striving to reach one another. Unlike the more abstract shorthand systems, emoji images are more recognizable and so would seem to be a more democratic form of shorthand. But communication is never that simple. Even if we were able to remove emojis from their material constraints—which we cannot—we would still encounter emojis as the smiling, frowning, winking poster children of Of Grammatology, challenging both the phonocentrism and logocentrism of de Saussure because they exemplify non-phonetic writing while signifying both absence and presence. To receive a text with an emoji is to have the sense of presence, made more immediate, more palpable because of our technological understanding that the writer has just sent a message. Emojis, like alphabetic words, always point somewhere else. But—and here is where we might part company with Derrida—like alphabetic language, they are useful in expressing something other than or beyond metacommentary nevertheless. Letters get received, rescued from their purloined places, and emojis, too, hit their marks, but in broad clouds, like electrons hovering around a nucleus of meaning.

More of our dear readers recognize ☺ as a smileyface than readers would have recognized Pitman’s shorthand · as "the," probably even in Pitman’s day. These readers, however, do not necessarily agree on its signification. The apparent iconicity of the ☺ is debatable. ☺ does not represent a word. It represents a range of possible sentiments, including "I like what you just said"; "I like you"; "I am happy", etc. Moreover, smiling itself is culturally dependent. The emoji is not insulated from the maddening or, some would say delightful soap-bar quality of all communication. Emoji Cro-Magnon might have intended the smiley first, foremost and ONLY to clarify the tone of a previous expression so that readers understood that the expression was not to be taken seriously, as in "I'm joking here," yet it has since been used to express a range of other sentiments, and may or may not be used to clarify the tone of a previous expression. The emoji ☺ may point us in the direction of lightheartedness, but even among speakers from similar cultures, irony and sarcasm are always possibilities. As ever, context is king.

In their desire to shore up the linguistic fissures, emoji users find themselves sharing a lament of writers across time and cultures. We might recall T. S. Eliot bemoaning the "shabby equipment, always deteriorating" available to the poet in "East Coker," or Italo Calvino observing that "The struggle of literature is in fact a struggle to escape from the confines of language; it stretches out from the utmost limits of what can be said; what stirs literature is the call and attraction of what is not in the dictionary" (qtd. in Gabriele 59). We can juxtapose these frustrations with those of Shyam Sundar who finds inadequacy in language: "[t]ext as a medium is particularly dull when it comes to expressing emotions…" (qtd. in Wortham). While Sundar's observation is expressed neither as a poem nor as a deep meditation on art, at its core, it joins with Eliot and Calvino in its exasperation with the limitations of the alphabetic language. But Sundar is neither poet nor novelist. He is co-director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University and his solution for escaping the language prison is neither poetry nor prose. Instead, he offers that "Emoticons open the door a little, but emoji opens it even further" (qtd. in Wortham). Admittedly, Sundar's reference to "dull text" might be enough to make a humanist or any lover of literature…

.

.Anyone who has ever wept or laughed or been stirred to action after reading would surely want scare quotes around "dull." For our entire lives, texts have been anything but dull. (Well, maybe a few.) But to be fair to Sundar, he's referring not so much to Shakespeare as he is to the quotidian texts sent by phone, the dozens or hundreds or thousands of messages sent every day by individuals when they are walking or waiting at the dentist or sitting in class or driving down the Interstate, often in front of me. He is, in a sense, seeking to liven the language of the everyday. Sundar is reflecting on quotidian language that does not fly in the rarified air of the published poem or squat on a marble museum pedestal. He wants to change the register of the daily exchange of Every Texter. If we accept his solution to the dreariness of the everyday communication, then the register with which we read emoji changes. For a brief Derridean moment, a friend’s emoji-graced message, texted in the middle of the day, constitutes an always-in place meditation on words’ shortcomings, a challenge to the limits of what we think is fundamental. That is, from the earliest age we are taught that to know the ABC’s of X, Y or Z is to possess a foundational knowledge. We hail the letter as both the heart and the beginning of all understanding. Placed in this context, the sending of a  , in its very presence, suggests “the ABC’s of the matter are and always will be unfit for the task of communicating what I have to say to you.” There is more to emoji than meets the glance. At the moment, these airy icons may prevent such a heavy interpretation. But it may be worth bearing in mind both that the sender of an emoji we cannot quite fathom is indeed attempting to express the inexpressible, to say that there is something he or she thinks or feels that is beyond the smooth gloss of letters. And if we can at least sense that sentiment coming from someone who is trying to reach us, we can move a bit closer to them—whether they are family or friends or students or even administrators.

, in its very presence, suggests “the ABC’s of the matter are and always will be unfit for the task of communicating what I have to say to you.” There is more to emoji than meets the glance. At the moment, these airy icons may prevent such a heavy interpretation. But it may be worth bearing in mind both that the sender of an emoji we cannot quite fathom is indeed attempting to express the inexpressible, to say that there is something he or she thinks or feels that is beyond the smooth gloss of letters. And if we can at least sense that sentiment coming from someone who is trying to reach us, we can move a bit closer to them—whether they are family or friends or students or even administrators.

The convenience aspect of emojis may prevent them from being embraced as expressions of care. We cannot deny the speed that emoji usage affords. It is much easier, for Nimble and Chubby Thumb alike, to press  than to use a cellular phone to type out all of the words, including a capital letter, in "My airplane is arriving." Indeed, the debut of this airplane arrival emoji, one of 270 emoji newly approved by the Unicode Consortium, prompted New Yorker writer Ian Crouch to observe, only slightly tongue in cheek: "it's difficult to imagine how we lived without [certain emoji characters] for so long." Within specific contexts, emojis offer instantaneous connection. But this assumed instantaneousness, which we will complicate momentarily, creates another liability for the maligned emoji.

than to use a cellular phone to type out all of the words, including a capital letter, in "My airplane is arriving." Indeed, the debut of this airplane arrival emoji, one of 270 emoji newly approved by the Unicode Consortium, prompted New Yorker writer Ian Crouch to observe, only slightly tongue in cheek: "it's difficult to imagine how we lived without [certain emoji characters] for so long." Within specific contexts, emojis offer instantaneous connection. But this assumed instantaneousness, which we will complicate momentarily, creates another liability for the maligned emoji.

Because of emoji ease, receivers of emoji text may take offense at receiving  instead of a note, sharing the sentiment of President Obama who expressed relief that his daughter had chosen an alphabetic path to his affection: "Malia, to her credit, wrote a letter to me for Father's Day, which was obviously much more important to me than if she had texted an emoji, or whatever those things are" (qtd. in Walker). So the ease and speed of emojis have caused them to be rejected as acceptable conveyers of heart-felt affection. Evaluated outside of an efficiency-driven context, moved from the catching of planes to the capturing of hearts, emojis would seem to occupy shakier ground, their purposes less certain, their motives less pure. The daughter who casually pastes

instead of a note, sharing the sentiment of President Obama who expressed relief that his daughter had chosen an alphabetic path to his affection: "Malia, to her credit, wrote a letter to me for Father's Day, which was obviously much more important to me than if she had texted an emoji, or whatever those things are" (qtd. in Walker). So the ease and speed of emojis have caused them to be rejected as acceptable conveyers of heart-felt affection. Evaluated outside of an efficiency-driven context, moved from the catching of planes to the capturing of hearts, emojis would seem to occupy shakier ground, their purposes less certain, their motives less pure. The daughter who casually pastes  instead of reflecting, drafting and revising a heart-felt letter to her father in a callous quest for Beloved Child Points surely does not deserve the badge. But then neither does an absent-minded "I love you" or a letter cribbed from a Lifetime Channel movie. Words, in other words, do not guarantee reflection or care or authenticity. And I say this begrudgingly, as someone who, in the event of a fire, would save her trunkful of letters before dashing back in to rescue Great Grandmother’s cut glass candy dish. But I say this also as someone who has dashed off a lazy "that's great!!!" (3 !!! indicating more effort than a lackadaisical!) in response to a friend's happy news. The medium is not necessarily the message; context counts. Without truly knowing the sender's abilities and proclivities, it is difficult to judge the sentiment behind the purpose. Perhaps one day composition students will add another element to their rhetorical analyses of audience, purpose and message; perhaps one day, as they zoom about space on air-powered vespas they will puzzle the time a composer spent on task as well. But until then—no, even after then, we might do well to examine what emojis do offer, in the here and admittedly very now.

instead of reflecting, drafting and revising a heart-felt letter to her father in a callous quest for Beloved Child Points surely does not deserve the badge. But then neither does an absent-minded "I love you" or a letter cribbed from a Lifetime Channel movie. Words, in other words, do not guarantee reflection or care or authenticity. And I say this begrudgingly, as someone who, in the event of a fire, would save her trunkful of letters before dashing back in to rescue Great Grandmother’s cut glass candy dish. But I say this also as someone who has dashed off a lazy "that's great!!!" (3 !!! indicating more effort than a lackadaisical!) in response to a friend's happy news. The medium is not necessarily the message; context counts. Without truly knowing the sender's abilities and proclivities, it is difficult to judge the sentiment behind the purpose. Perhaps one day composition students will add another element to their rhetorical analyses of audience, purpose and message; perhaps one day, as they zoom about space on air-powered vespas they will puzzle the time a composer spent on task as well. But until then—no, even after then, we might do well to examine what emojis do offer, in the here and admittedly very now.

Despite the very contemporary, post-Fordist zeitgeist into which the emoji has popped, it nonetheless links us to our earliest efforts at expression—pictograms, petroglyphs and petrographs. John Berger acknowledges the both/and quality of images as the earliest symbols, predecessors to the symbolisms of alphabetic language:

"What distinguished man from animals was the human capacity for symbolic thought, the capacity which was inseparable from the development of language in which words were not mere signals, but signifiers of something other than themselves. Yet the first symbols were animals. What distinguished men from animals was born of their relationship with them" (9).

Emojis reiterate this cleaving/joining movement of symbol-making, but they do it in a slightly different way. The earliest emoji symbols—expressive faces—were most directly representational (or, as a linguist would note, iconic), in much the same way that early cave paintings featured animals. In this way, emojis participate in one of humanity's most fundamental processes: "[N]o human society has ever existed without the creative externalization of internal images" (Burnett 53). Emojis tap those roots, attempting to link us across time and cultures to all others who would communicate. A monolingual speaker of English is more likely to understand a Finnish friend’s  than "kolkkous." Emojis operate at the level of the non-discursive, potentially filling a gap that separates even speakers of the same language. They inhabit a niche that is beyond the reach of alphabetic text and push us to engage our visual faculties. Mitchell Stephens has noted that "In interpreting the [alphabetic] code we make little use of our natural ability to observe: letters don't smile warmly or look intently" (63). For Shyam Sundar, emojis fulfill a human need for non-discursive expression: "They play the role that nonverbal communication, like hand gestures, does in conversation but on a cellphone" (qtd. in Wortham). Rather than having alphabetic text fly solo in conveying a message, emojis expand the possibilities of what might be expressed. Since their inception, emojis have been swept up by users with bigger ambitions for them, and in doing so have made the leap from being "users" to being "rhetors," joining a classic tradition that dates back to Ancient Greece and Rome. Catherine Hobbs explores a history of rhetoric tied to visualization, explaining that Greco-Roman law cases often depended on both the presentation of actual objects as well as orators’ abilities to use visual imagery in persuading their audiences ("a scar, a wound, a bloody weapon or a toga") [58], a practice that continues in contemporary courtrooms, admittedly for better and for worse. The desire to argue effectively, to reach an audience through images and words, has a long and revered history that emojis have joined. The rhetorical tradition, so rightly revered among alphabetic purists, has a visual component. Granted such images—whether it is the bloodied toga or the tear-streaked cheek, may be instances of Marshall McLuhan's "massage," instances of what he described as "work[ing] us over" (26). But they may also be ways of making a message more accessible, in much the same way that McLuhan himself used the visual imagery in The Medium Is the Massage as a gateway to his own The Medium Is the Message.

than "kolkkous." Emojis operate at the level of the non-discursive, potentially filling a gap that separates even speakers of the same language. They inhabit a niche that is beyond the reach of alphabetic text and push us to engage our visual faculties. Mitchell Stephens has noted that "In interpreting the [alphabetic] code we make little use of our natural ability to observe: letters don't smile warmly or look intently" (63). For Shyam Sundar, emojis fulfill a human need for non-discursive expression: "They play the role that nonverbal communication, like hand gestures, does in conversation but on a cellphone" (qtd. in Wortham). Rather than having alphabetic text fly solo in conveying a message, emojis expand the possibilities of what might be expressed. Since their inception, emojis have been swept up by users with bigger ambitions for them, and in doing so have made the leap from being "users" to being "rhetors," joining a classic tradition that dates back to Ancient Greece and Rome. Catherine Hobbs explores a history of rhetoric tied to visualization, explaining that Greco-Roman law cases often depended on both the presentation of actual objects as well as orators’ abilities to use visual imagery in persuading their audiences ("a scar, a wound, a bloody weapon or a toga") [58], a practice that continues in contemporary courtrooms, admittedly for better and for worse. The desire to argue effectively, to reach an audience through images and words, has a long and revered history that emojis have joined. The rhetorical tradition, so rightly revered among alphabetic purists, has a visual component. Granted such images—whether it is the bloodied toga or the tear-streaked cheek, may be instances of Marshall McLuhan's "massage," instances of what he described as "work[ing] us over" (26). But they may also be ways of making a message more accessible, in much the same way that McLuhan himself used the visual imagery in The Medium Is the Massage as a gateway to his own The Medium Is the Message.

Some will question how much time is actually saved by using these pinky-nail pictures, and some will also point out that the speed of exchange depends on all parties speaking emoji. If Nimble Thumb punches out  , but her friend doesn't understand and spends most of the morning puzzling out the possibilities that

, but her friend doesn't understand and spends most of the morning puzzling out the possibilities that  might mean, the message is purloined, composed but never received, the plane arriving but forever unmet. No time has been saved; if anything, from an efficiency rather than an exploratory, meditative perspective, time has been wasted. We are again faced with the importance of context and of discourse. Emoji efficacy works only if all parties speak the same emoji. Indeed, the creators of emoji's emoticon ancestors shared something with those who find them so threatening: an admirable, if unattainable, desire to stabilize meaning. Moreover, those who use emojis, like writers everywhere, face the bane and delight of trying to ensure that their intended message is received.

might mean, the message is purloined, composed but never received, the plane arriving but forever unmet. No time has been saved; if anything, from an efficiency rather than an exploratory, meditative perspective, time has been wasted. We are again faced with the importance of context and of discourse. Emoji efficacy works only if all parties speak the same emoji. Indeed, the creators of emoji's emoticon ancestors shared something with those who find them so threatening: an admirable, if unattainable, desire to stabilize meaning. Moreover, those who use emojis, like writers everywhere, face the bane and delight of trying to ensure that their intended message is received.

Emojis are still in their language cradle. Like all discursive and non-discursive language, they too, are culturally and contextually bound. Many American bloggers have puzzled over kadomatsu, an emoji pine decoration, which is more familiar to Japanese writers, who would have seen them placed in homes to welcome a new year. In instances of cultural disconnect, those unfamiliar with the tradition have sent the kadomatsu as a sign of disrespect, mistaking it for a middle finger icon. While some images cross cultural borders, not all do. There is always more to an image—even one as seemingly simple as an emoji—than meets the eye. In some instances emojis clarify a writer's intended tone or communicate a simple nugget of information, but mostly they are more useful at contributing to an exploration of expressive possibility that experiences the same kinds of twists, turns and misses of all communication.

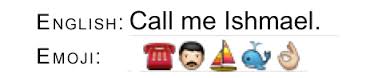

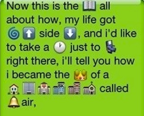

Consider Fred Benenson's rewritten version of Moby Dick:

Benenson's crowd-sourced, Kick-Starter-funded rewritten version of Moby Dick, Emoji Dick, was accepted into the Library of Congress in February 2013. As with any translation, Benenson's act was creative and subjective. (I still read that opening line as "phone, mustache face, sailboat, whale, ok.") Indeed, in an interview Benenson himself acknowledged the many interpretive choices he had to make during the translation: "I fully admit that there are large portions of the book that don't make any sense, and there are a number of reasons for that" (qtd. in Goldmark). We could view Benenson's efforts as an act of literary apostasy, but we could also see it as a work of art in its own right, a brave foray into challenging and unexplored literary waters in search of an elusive and formidable goal. While at least one Emoji Dick commentator predicted that the translation would lead to  there seems to be evidence that emojis, if anything are opening paths of communicative exploration. VoidWorks, a Singapore-based-app development studio, has released an app that allows users to "emojify" any photo by converting pixels into emoji; emoji poetry is everywhere, and there's a Tumblr blog, Narratives in Emoji (http://narrativesinemoji.tumblr.com) that includes emoji translations of Les Miserables, The Titanic and Groundhog Day. Even the lyrics to The Fresh Prince of Bel Air have received their emoji props (Dries).

there seems to be evidence that emojis, if anything are opening paths of communicative exploration. VoidWorks, a Singapore-based-app development studio, has released an app that allows users to "emojify" any photo by converting pixels into emoji; emoji poetry is everywhere, and there's a Tumblr blog, Narratives in Emoji (http://narrativesinemoji.tumblr.com) that includes emoji translations of Les Miserables, The Titanic and Groundhog Day. Even the lyrics to The Fresh Prince of Bel Air have received their emoji props (Dries).

The art world is also enjoying the fruits of emoji labors. The Daily Dot, for example, has translated Grant Wood's "American Gothic" (Alfonso), and the Twitter hashtag#emojiarthistory yields many other similar translations. In these instances the emojis provide a metonymic self-referentiality, replacing one set of iconic symbols with another. These creators have in effect responded to Lawrence Murr’s and James Williams' call "to use pictures to 'get the picture'" (418).

In some instances emoji have themselves been subject to translation, as Justine on YouTube demonstrates in this aural representation of them:

In their visuality, their connection to gestures and their digitized form, emojis fit squarely in the social future called for by The New London Group in their 1996 "Pedagogy of Multiliteracies." An international collaborative aimed at developing new pedagogies that would respond to changing literacies brought by increasing globalization, cultural, social diversity and changes in technology, the group called for a literacy pedagogy of "available designs." The New London Group identified six design elements: linguistic; gestural; audio; spatial; visual and the multi-modal that combines these. Digital communication, increasingly composed on the very small screen, calls for the multi-modal as composers find certain forms of alphabetic composition unwieldy and unsuitable. In some instances, composers will be able to choose their medium, deciding if what they have to say is best expressed via the page, or if they need the more visual affordances of the computer screen or if they need the speed of texting via the tiniest screen of them all. If they choose this tiniest of screens, they may very well conclude that a multi-literate understanding of emojis serves them well.

Almost a decade prior to the New London Group manifesto, Murr and Williams would reason that "since language shapes our perception of reality it is clear that new concepts of language must be developed with the emergence of the visual culture. Just as the practice of language in Western civilization, as served by speech and memory, was altered by the invention of an alphabet and later its encoding in books through monotype, so must it be altered again as a result of the invention of visual tools" (415). Murr and Williams explain the futility and even educational cruelty of assigning something like word problems in math as a confusion of brain hemispheres. Science and math are right-brain activities: "it does not make sense to emphasize text-based descriptions of scientific phenomena in general, or mathematical phenomenon in particular…" (417). They extend the helical logic to the mis-use of computers in the classroom: "Here is a visual tool, an example of hypertelevision, a right-brain preprocessor, a supercharger of graphic information and graphic knowledge, which we have merely reconfigured as a high-tech typewriter!" (417). As antidote, they advocate a need for "some attention to graphic forms, drawing, painting and the visual arts, by raising our consciousness of symbols, by connecting text and graphics through the creation of language networks…"(418). Perhaps work with emojis will provide an entryway for such balance. Calls for the visual in the composition classroom have a long history. (See for example, Fleckenstein; George; Kress; Selfe; Stroupe; Yancey). The explorations that have already begun in classrooms are beyond the scope of this essay, but it is worth mentioning that emoji work has the potential to support the same kinds of rich learning experiences we seek in composition classes: a recognition of a multi-literate world; a platform for communicative play, experimentation and creativity; a basis for analysis of cross-cultural communication, identity and representations, and the threads of a re-materialized concept of composing.

Emojis have neither destroyed nor rescued words. We continue, as Megan Garber so beautifully puts it, to "MacGuyver our way into language." At the end of the day, emojis are just as much a reflection of their creators as words, with just as much potential to express, explore, kvetch and ultimately connect us to others. Though in some instances they supplant words entirely, they also open up new vistas of exchange and creativity. They are in a sense, the words that got away, and then returned. As smiles and frowns and jetliners.

Lisa Lebduska teaches writing and directs the college writing program at Wheaton College in Massachusetts. Focused on the intersections and eruptions among composition, technology and people, her work has appeared in such publications as WPA Journal, CCC, Narrative, Writing on the Edge, and Technological Ecologies and Sustainability: Methods, Modes, and Assessment.

Acknowledgements: I wish to thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for providing me with summer research support, including those allowing me to work with Hailey Heston (Wheaton Class of 2018), who found the Library of Congress images used here, and whose photoblog serves up many an image for thought.

Works Cited

Berger, Jon. "Why Look at Animals?" About Looking. New York: Random House, 1988. 1-28. Print.

Brownlee, John. "Where Do Emoji Come From?" Co.design. 30 June 2014. Web. 1 July 2014.

Burnett, Ron. How Images Think. Cambridge: MIT, 2004. Print.

Crouch, Ian. "New Emojis, but No Hot Dog." Culture Desk. The New Yorker 18 June 2014. Web. 20 June 2014.

Dillon, Sam. "In Test, Few Students Are Proficient Writers." New York Times. New York Times, 3 April 2008. Web. 20 July 2014.

Dries, Kate. "People Have iPhones and They're Not Afraid to Use Them." Buzzfeed. 5 February 2013. Web. 10 June 2014.

Eliot, T.S. East Coker. London: Faber and Faber, 1942. Print.

Fleckenstein, Kristie S. "Inviting Imagery into Our Classrooms." Language and Image in the Reading Writing Classroom: Teaching Vision. Eds. Kristie Fleckenstein, Linda T. Calendrillo and Demetrice Worley. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002: 3-26. Print.

Gabriele, Thomasina. Italo Calvino: Eros and Language. Fairleigh Dickinson P., 1994. Print.

Garber, Megan. "How to Tell a Joke on the Internet." The Atlantic Monthly. 24 April 2013. Web. 16 May 2013.

George, Diana. "From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing." College Composition and Communication. 54.1. (2002): 11-38. Print.

Goldfield, Hannah. "I Heart Emoji" The New Yorker. 16 October 2012. Web. 16 May 2013.

Goldmark, Alex. "Inside the Mind That Translated Moby Dick into Emoji" New Tech City. 27 February 2014. Web. 19 March 2014.

Haiman, John. Talk Is Cheap: Sarcasm, Alienation and the Evolution of Language. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1998. Print.

Hobbs, Catherine L. "Learning from the Past: Verbal and Visual Literacy in Early Modern Rhetoric and Writing Pedagogy." In Fleckenstein, Calendrillo and Worley. 27-44. Rpt. in Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook. Ed. Carolyn Handa. Boston:Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004: 55-71.

Holland, Jessica. "Emoji: A Tiny Graphic Can Be Worth a Thousand SMSes." The National. 7 April 2013. Web. 19 March 2014.

Kelion, Leo. "Apple Seeks Greater Racial Diversity." BBC News Technology. 26 March 2014. Web. 10 June 2014.

Kress, Gunther. Literacy in the New Media Age. New York: Routledge, 2003. Print.

MacDonald, Susan Peck. "The Erasure of Language." College Composition and Communication. 58.4 (2007): 585-625. Print.

Marsden, Rhodri. "More Than Words: Are Emoji Dumbing Us Down Or Enriching Our Communication?" The Independent. 11 May 2013. Web. 20 June 2014.

McLuhan, Marshall. The Medium is the Massage. New York: Random House, 1967. Print.

Miller, J. Abbott and Ellen Lupton. "A Natural History of Typography." Bierut, Michael, William Drenttel, Steven Heller, and D.K. Holland, Eds. Looking Closer: Critical Writings on Graphic Design. Vols. 1-2. New York: Allworth, 1994, 1997. 19-25. Print.

Mitchell, W. J. T. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: U. of Chicago P., 1986. Print.

Murr, Lawrence E. and James B. Williams. "Half-Brained Ideas about Education: Thinking and Learning with Both the Left and Right Brain in a Visual Culture." Leonardo 21.4 (1988): 413-419. Print.

New London Group. "A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures." Harvard Educational Review, 1996 66 (1), 60-92. Print.

Rock, Margaret. "From Talk to Telepathy." Mobiledia. 8 July 2013. Web. 1 July 2014.

Selfe, Cynthia. "Toward New Media Texts: Taking Up the Challenges of Visual Literacy." In Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for Expanding the Teaching of Composition. Eds. Anne Francis Wysocki, Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia L. Selfe, Geoffrey Sirc. Utah State P, Logan: Utah, 2004:67-110. Print.

Smith, Aaron. "African Americans and Technology Use: A Demographic Portrait." Pew Research Internet Project. 14 January 2014. Web. 6 June 2014.

Stephens, Mitchell. The Rise of the Image, the Fall of the Word. New York: Oxford UP, 1998. Print.

Stroupe, Craig. "Visualizing English: Recognizing the Hybrid Literacy of Visual and Verbal Authorship on the Web." College English 62.5 (2000): 607-632. Print.

Trimbur, John. "Delivering the Message: Typography and the Materiality of Writing." Rhetoric and Composition as Intellectual Work. Ed. Gary Olson. Carbonddale: Southern Illinois UP, 2002. 188-202. Rpt. in Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Sourcebook. Ed. Carolyn Handa. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s P., 2004: 260-271. Print.

Walker, Hunter. "President Obama Is Glad He Didn't Get Emoji for Father's Day." Business Insider. 17 June 2014. Web. 2 July 2014.

Wilson, James A. and Walter R. Gove. "The Intercohort Decline in Verbal Ability: Does It Exist?" American Sociological Review. 64.2 (1999): 253-266. JSTOR. Web 20 July 2014.

Wortham, Jenna. "Whimsical Texting Icons Get a Shot at Success." 11 December 2011. New York Times. n.p.17 June 2014. Web.

Yancey, Kathleen. "Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key." College Composition and Communication. 56:2 (2004): 297-328. Print.

Images

Alfonso, Fernando III. "Reinterpreting Classic Works of Art with #emojiarthistory." The Daily Dot. 13 February 2013. http://www.dailydot.com/culture/emoji-art-history-tate-getty/

Babel Fish Diagram. Hitchhiker Wiki. n.d. Web. 1 July 2014.

Cyrus, Miley Ray. "RT If You Think There Needs to be an #emojiethnicity Update." 18 December 2012, 7:05 p.m. Tweet.

Doctorow, Cory. "Crowdsourced Translation of Moby-Dick into Emoji." Boing Boing. Boing Boing, 21 September 2009. Web. 20 July 2014.

"Emoji Fortunes." Baker’s Blog. 6 June 2013.

"Emojify: Turn Pixels into Emoji Emoticons to Make Unique Art Images." Appszoom. <http://www.appszoom.com/iphone-apps/photo_video/emojify-turn-pixels-into-emoji-emoticons-to-make-unique-art-images_hlszh.html>

Heston, Hailey. "Light Bulb of Ideas." Wandering, Wondering. 29 March 2014. Web. 14 July 2014.

iJustine. "Emoji Emotions." YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6B0NBVT6VP4.

Kahn, Justin. "How to Get Emoji Keyboard on iPad." ipad Notebook: Tips, Thoughts & Apps. Web. <http://ipadnotebook.wordpress.com/2012/10/10/how-to-get-emoji-keyboard-on-ipad/>.

Lee, Eric. "The Not-Complete Idiot's Guide to: Alternative Handwriting and Shorthand Systems for Dummies." n.d. Web. 10 June 2014.

Psar, Ira. "The Origins of Writing." In Heilbrun Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metroploitan Museum of Art. October 2004. Web. 14 October 2014.

Trahan, Heather. "A Composition in Film." http://vimeo.com/6902118.

"Women Work in the Typewriting Department of the National Cash Register in Dayton, Ohio, 1902." Library of Congress. Web.

The purpose of all quoted material here is to quote and cite material within the bounds of academic fair use. I have attributed all authors and creators, providing a Works Cited.

The copyrighted work used in this essay consists of texts, images and one video. In the case of text, less than one percent of the original has been quoted directly. Images have been used in their entirety. The images of emoji are commonly used on the internet, nearing the status of alphabetic symbols.