Just six days after his inauguration on January 20th, Barack Obama gave his very first interview not to the English-language news media in the United States but rather to Hisham Melhem of the Al Arabiya News Channel. This was an extraordinary decision by the new President, and it was an extraordinary interview. In contrast to post-9/11 Bushspeak about the Islamic world to a home audience, Obama chose to speak about the possibilities of peace and justice in the Middle East to an Arabic-speaking audience. In contrast to a "war on terror" and "islamofascism," Obama spoke of diplomacy and negotiation between different groups with contending interests and goals. The three most repeated, and most emphasized, words in the interview were "respect," "listening," and "communication." Yes, indeed, this was an extraordinary speech in tone, content, and choice of audience.

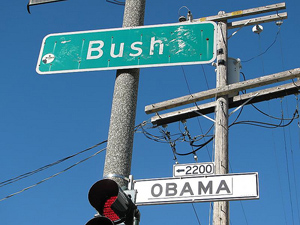

Compare, for instance, Bush's rhetoric of political and moral certainty with Obama's insistence on inquiry and engagement. In a typical statement Bush said the following in his May 2008 speech to the Israeli Knesset:

The fight against terror and extremism is the defining challenge of our time. It is more than a clash of arms. It is a clash of visions, a great ideological struggle. On the one side are those who defend the ideals of justice and dignity with the power of reason and truth. On the other side are those who pursue a narrow vision of cruelty and control by committing murder, inciting fear, and spreading lies. (Bush)

Here, in contrast, is Obama speaking on the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians:

I think the most important thing is for the United States to get engaged right away. And George Mitchell is somebody of enormous stature. He is one of the few people who have international experience brokering peace deals. And so what I told him is start by listening, because all too often the United States starts by dictating—in the past on some of these issues—and we don't always know all the factors that are involved. So let's listen. He's going to be speaking to all the major parties involved. And he will then report back to me. From there we will formulate a specific response. (Al Arabiya News Channel)

In Bush's rhetoric, the fundamental question we faced in our foreign policy towards the Middle East was how to protect ourselves from Islamic terrorism, and the answer to that question was violence. He called this the war on terror, and that concept gained almost immediate hegemony in the U.S., becoming a neutral term of reference in the media, in public debates, and in political rhetoric everywhere. This singular focus on terrorism was perversely narcissistic in character because it organized the complex problems and events of the contemporary Middle East around our traumatic experience on 9/11. Let me explain what I mean by this. Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld never tired of repeating the idea that the primary motive of the 9/11 terrorists, and of Islamic terrorism in general, was their hatred of our freedoms and our goodness.[1] In other words, the antagonist in this story serves only as a foil for the protagonist's character. The terrorist proves our goodness, enables our heroism, and justifies our violence. He doesn't, in any meaningful way, have his own story or reason for being. Like Darth Vader behind his mask in Star Wars, the terrorist hides in Afghanistan or Pakistan or among Iraqi civilians. But while he lurks mysteriously in the shadows, his role in the story is quite obvious and public. His job, so to speak, is to incarnate evil and then to die under our sword at the end. That is all we know of him, and all we need to know. This narcissistic logic is how and why the invasion and occupation of Iraq continued to make sense to the Bush administration—as the central front in the war on terrorism—despite the absolute lack of specific rationale for it: it satisfied our need for an evil antagonist upon whom to inflict a kind of sacramental violence. One consequence of this formulation was to effectively associate the entire Islamic world with extremist jihadism, an association that has deeply alienated and angered so many Muslims.

In contrast, Obama has tended to tell a much different kind of story involving real, historical characters whose destinies are not foreordained. In Obama's story, what happens is a matter of history: what human beings decide to do with their circumstances. Of course, an important part of how people make history is how they use words and symbols to represent circumstances and motives to themselves and to one another. This is why Obama has very carefully steered clear of phrases such as "war on terrorism"—because, as he recognized in his recent interview with Anderson Cooper, "words matter." Words matter, and this is why Obama makes a pointed rhetorical effort in the interview with Al Arabiya to isolate jihadism as a specific phenomenon that is unrepresentative of, and peripheral to, the Muslim world. Also, he characterizes the problems of the Middle East not in terms of U.S. interests, but rather in diplomatic terms as a field of contention between a number of parties whose interests are legitimate but do not coincide. In other words, he doesn't view the Middle East through the narcissistic lens of a mythological war between good and evil whose outcome is inevitable. Instead, he represents the issues and conflicts of the Middle East as an ongoing story of competing interests. His words indicate not a belief in the inevitable victory of good over evil, but rather a belief in international politics: he argues that with attention, work, and diplomacy the competing interests and conflicting parties of the region can negotiate their differences without violence. In this context, the U.S. becomes one, but not the only, party that has a stake in the outcome. This is clear in the Al Arabiya interview even though he is referring in the following quotation specifically to Israeli-Palestinian relations:

…the language we use matters. And what we need to understand is, is that there are extremist organizations—whether Muslim or any other faith in the past—that will use faith as a justification for violence. We cannot paint with a broad brush a faith as a consequence of the violence that is done in that faith's name.

I think anybody who has studied the region recognizes that the situation for the ordinary Palestinian in many cases has not improved. And the bottom line in all these talks and all these conversations is, is a child in the Palestinian Territories going to be better off? Do they have a future for themselves? And is the child in Israel going to feel confident about his or her safety and security?

I think that what you will see over the next several years is that I'm not going to agree with everything that some Muslim leader may say, or what's on a television station in the Arab world—but I think that what you'll see is somebody who is listening, who is respectful, and who is trying to promote the interests not just of the United States, but also ordinary people who right now are suffering from poverty and a lack of opportunity. I want to make sure that I'm speaking to them, as well. (Al Arabiya News Channel)

Towards the end of the interview Obama says that "ultimately, people are going to judge me not by my words but by my actions and my administration's actions" in the Middle East. He is, I think, both right and wrong about this. Of course, he must follow his rhetoric with genuine diplomacy—genuine in the sense that it regards as both real and significant the interests not just of Israel but also of the Arabic and Islamic world—but at the same time I believe the sea-change in perspective and attitude expressed here itself constitutes an impressive symbolic "action." This doesn't mean that Obama is going to be the Great Visionary of peace in the Middle East. Some of his Middle East policy inclinations do indeed represent a continuity of the military approach of the Bush administration (eg. Afghanistan). And, like many others, I am deeply disappointed in Obama's silence about the ghastly Israeli invasion of Gaza. However, this should not make us lose sight of what is indeed dramatically different about Obama's rhetoric and his approach to the Middle East. Edward Said once described the importance of beginnings in terms of the "characteristic inclusiveness" they create within which whatever comes next can develop (Said 1975, 12). As a beginning statement, Obama's interview with Al Arabiya—although it lacks the stage drama and loftiness of some of his grand speeches—is his finest rhetorical moment thus far because, potentially, the characteristic inclusiveness it inaugurates can open the door to new representations, and new ways of thinking about foreign policy in the Middle East.

Notes

[1] Click here for a well-made right-wing propaganda piece called "Why Do They Hate Us?" using Bush's words and visual imagery.

Works Cited

- Al Arabiya News Channel. Obama Tells Al Arabiya Peace Talks Should Continue . 27 January 2009. 27 January 2009 <http://www.alarabiya.net/articles/2009/01/27/65087.html>.

- Bush, George W. Prepared Text of Bush's Knesset Speech. 15 May 2008. 27 January 2009 <http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121083798995894943.html?mod=googlenews_wsj>.

- Said, Edward. Beginnings: Intention and Method. New York: Columbia University Press, 1975.