The Biopower of Zombies: Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Horde

Mary Hendegren

I like zombies. I really like zombies. But I’m not the only one: why do so many of us seem to be enjoying a zombie moment? What does it say about our fears of a decentralized government and the power of human bodies? And what is that faintly discernable groaning sound? In this article, I draw on the theories of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri as well as Foucault's "biopower" concept to examine our collective fascination with a collective threat.

For my birthday this year, my sister sent me a grey t-shirt with grey writing that reads, “The hardest thing about a zombie apocalypse will be pretending I’m not excited.” I guess I shouldn’t be surprised; I read zombie books and watch zombie movies and make zombie jokes. Twice, I’ve been zombified as part of a 5K and every time I go out for a morning run, I play a zombie running app1. But what is most surprising, perhaps, is where my sister got this t-shirt. “It was on Etsy and I thought of you,” she said. Etsy sells zombie t-shirts.

Me, I liked zombies before they were cool. I’m like a zombie hipster now that zombies have invaded the mainstream, from historical fiction to video games to a whole sub-set of the CDCs’ disaster prep guides to children’s Halloween costumes, including zombie ballerinas, monkeys and skate punks.

I admit I feel a little betrayed by my standby monster.

I needn’t be, of course. I should be happy that everyone’s enjoying zombies as much as I always have. The question is, though, why are they enjoying zombies this much? Why are people who typically stand at a distance from the horror genre so engaged by the brain-eating living dead?

This is more than a casual question. In Rhetorical Dimensions in Popular Culture, Barry Brummett points out that popular culture betrays the concerns and priorities of a time, place and people. Brummett’s study of popular culture moved beyond just looking at one movie or one book to see how widespread ideas and tropes could capture the public imagination. Horror trends are some of the most obvious signs; what are a group of people concerned about? Well, what are they scared of? Brummett writes about the way haunted houses and vampires captured the imagination of the 1970s and 80s in America as we collectively worked through political issues like the lingering Cold War and the threat of growing technology. It’s more than slightly likely that all this zombie-philia really means something.

Take a moment to consider the zombie as we have come to know it: the living dead stagger about searching for human flesh—or, more specifically, brains—without much finesse. The “infected” swarm through the streets, without a leader and without individuality. Angry and hungry, they spring after any sign of life like a lion, or more accurately, like a pack of hyenas. Zombies are always in horde formation. Think about it: can you name a single, famous zombie?

This view is actually radically different from early 20th-century accounts of the zombie, where the fear was more about the villainous individual who could control a zombie. David Chalmers (1996) calls these zombies the “Haitian form,” although they permeate many Caribbean, African and Central American cultures. These living, sleepwalking worker zombies still terrorize popular culture in places like South Africa,2 but they don’t look like the guys lumbering around movies and video games for the past fifty years. Hollywood zombies have changed. You know, we might not even recognize the zombie of Caribbean and African folklore that is expressed in the early 1930s films like Bela Lugosi’s White Zombie (1932) and its Cambodian “sequel,” Revolt of the Zombies (1936). In fact, in such films, the threat isn’t the zombies themselves, but those who control the zombie. How recently have you thought to yourself, “Man, I’m so freaked out by bokors”? Here’s a table comparison so you can see at a glance how much zombies have changed from the traditional folklore in just a few decades.

|

Early 20th-Century Zombie |

Post-1960s Zombie |

Cause |

Animated by magic or “voodoo” |

Explained by science, usually viral |

Control |

Manipulated by a bokor (sorcerer), without any will of its own |

Self-driven, usually by hunger or rage |

Location |

Exotic monster of Caribbean or West African provenance |

Local: neighbors, co-workers, family are all potentially part of the horde |

Range |

Small—often just one factory or village is under threat |

Widespread—usually worldwide and apocalyptic |

Appearance |

Often like a healthy, if somewhat spacy, person |

Grotesque, semi-decomposed |

Sociability |

Individual threat |

Collective swarms |

Movement |

Slow, painful movement |

Fast, and increasing faster |

Goals |

Fulfill the needs of the bokor including to work, fulfill mischief, etc. |

Consumption, with the collateral side effect of propagation |

Longevity |

Temporary. Defeated through stopping the bokor, counter-incantation |

Difficult to stop. Killed by a shot to the head or other destruction of the brain |

Our fascination with the zombie, it seems, has relatively little to do with the traditional incarnation of the monster and more with what we have made them into. Some of the fears that our society harbors have found expression in zombies since the late 1960s, and we have changed what we describe as a zombie to better fit the characteristics that most haunt us. It’s sort of an undead-chicken-and-undead-egg kind of thing.

Image 1: Brains she ain’t after. White Zombie (1932)

The first pivotal departure from traditional zombie lore was George A. Romero’s famously low-budget and low-key Night of the Living Dead (NOTLD) in 1968. When I was a kid, Night of the Living Dead was synonymous with horror films. When my older brothers were around 10 and 12, they once watched it while alone; when my parents returned, they discovered a small arsenal of homemade torches in the kitchen.

The Hedengren household was not the only one terrified by Romero’s innovative zombies. Millions of people have seen Night of the Living Dead since its release, and most of them have been similarly freaked out.3 The question in terms of popular culture rhetoric is less why Romero chose to change the zombie legend so drastically, but why Romero’s transformation resonates so powerfully with its contemporary audiences as something they recognize as zombie.

For instance, consider the way that the word zombie is applied to works that never use the term themselves. Romero’s film never uses the word zombie but refers to the monsters as “ghouls.” Romero’s audiences made a connection between these flesh-eating reanimated corpses and the hypnotized workers of earlier zombie movies. Richard Matheson’s 1954 I Am Legend has similarly been appropriated as a “zombie story” despite describing its ghouls as vampires.4 In both cases, our placing the works within the zombie genre is more a function of retroactively identifying characteristics that have come to be associated with zombies in the later half of the 20th century. Viral-spread, apocalypse-inducing, and collective maneuvering have become the criteria when going back and identifying these monsters as zombies, rather than the creators consciously expanding the genre.

Image 2: “Jus’ folks.” Night of the Living Dead (1968).

I’ve argued elsewhere (Hedengren 2003) that Romero’s Night of the Living Dead represents a post-war fear of the masses. NOTLD presents a perspective in which neither individual heroes nor individual villains have much influence on the sway of the world, but rather that power rests with the masses of people, whether millions of complacent and collaborative citizens in Hitler or Stalin’s nations, or the decentralized revolutions of the 1960s.

Romero’s depiction of zombies resonates so eerily with us because these ghouls are so critically different than the individual monsters, the solitary vampire, or mummy, or Frankenstein’s monster, who stalked through the horror films of the 1930s and ‘40s. Many of the monsters who dominated popular culture before NOTLD were loners, powerful and appealing. Often they were romantic, and even more often they were Romantic. From Dracula to the Swamp Thing, many of traditional Western monsters were Byronic tortured souls. Even the zombie masters of White Zombie and Revolt of the Zombie were individuals driven by powerful, but understandable passions. Romero’s zombies, though, are driven by something very different.

Instead of powerful individuals, motivated by love or greed or power, the move to the collective threat of the senseless horde suggests a fearsome democracy instead of aristocracy. There is a sort of reactionary vibe from this change; ordinary folks, bunkered up in the traditional American farm, complete with picket fence, can’t fathom the violence of people who have previously been so familiar, who never were particularly special in any way. As Jen Webb and Sam Byrnand have put it, “there is always something ‘nearly me’ about the monster” (84).

When the young protagonist in NOTLD meets her first zombie, there’s nothing particularly frightening about him; he looks like an ordinary man, maybe drunk, maybe with special needs. Romero himself has said that “there’s nothing about the make-up that tips you right away” that this lurching man is actually a soulless living dead (qtd. in Waller 272). Almost all of the zombies are similarly ordinary—dressed in overalls, housedresses, pajamas—just like you and me. News reports can tell the scared people at home why familiar faces have mobilized to destroy them, but even they emphasize the banality of the horde: “Ordinary looking people,” they report, are coming back from the dead to kill. As R. H. W. Dillard has put it, the living dead are “still recognizably ordinary” (68-9). I hate to belabor the point that there’s nothing particularly special about these monsters, but you have to compare their quotidian nature to other monsters we know, the aristocrats like Dracula or the mummy, or the spectacular aberrations like the Swamp Thing or Frankenstein. Zombies aren’t that special; after all, these monsters used to be your friends, your siblings, your children.

Not only did Romero collectivize and decentralize the zombie, creating the zombie horde, but he also brought zombies from the realm of magic into science, or at least the kind of movie science explained in news reports by Annie Dillard’s dad in a lab coat.5 Scientists and government officials crowd the broadcasts that the bunkered-down survivors watch, giving directions and, perhaps as important, explanations. In Romero’s flick, the reasoning is almost B-movie cliché: waves from outer space are controlling the staggering undead. 6

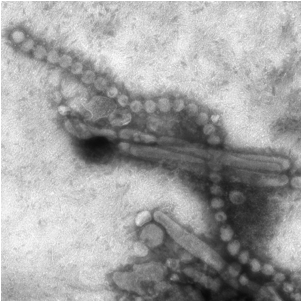

But by the time of the second great transformation of zombie lore, Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002), the standard zombie explanation was viral and our new “infected” zombies were very fast and very, very angry. In both NOTLD and 28 Days Later and in most zombie stories, there is a scientific explanation for how these once-people have gotten their brains corrupted by outside forces. Instead of being controlled by a powerful individual, their minds have been turned by forces beyond any one person’s control. The mysterious space rays in NOTLD may seem a bit hokey now, because the viral zombie has dominated the genre in the past twenty years. This viral metaphor is especially telling of our collective cultural fears.

Image 3: Going viral, from CDCs.

Image by Cynthia S. GoldSmith and Thomas Rowe.

The zombie phenomenon that started in the late 1960s and ‘70s reflects a fear of politically “infected” masses, rather than a fear of powerful and purposeful individuals. It’s also possible that this is why zombies have become so prominent in the past ten years. In the era of the 99% and the Arab Spring, are we reactionaries, terrified by the destructive power of the decentralized masses of people infected with dangerous ideas? Or is it that we find the new, leaderless order fascinating? The answer, frustratingly, is probably both. Consider the waves of euphoria that many Westerns first felt in the early expressions of revolutionary fervor in the middle east as ordinary people—people like you and me—rose up and fought against dictators. But then consider how that euphoria turned to discomfort as those ordinary people chose for their leadership political groups who didn’t support the West or Western ideals, or who even seemed tyrannical in their own right. At the time of this writing (Winter 2014), there have been similar cycles of adoration, fascination and then unease as the “ordinary masses” of Syria, Ukraine, and Thailand have moved against powerful individuals with seemingly lawless violence. We don’t know whether to champion or fear movements of the masses against a single, centralized figure. It seems like in an age that is increasing described as “post-national,” we have less fear of individual political leaders like Count Dracula or individual scientists like Dr. Frankenstein influencing our world, than we do the threat of huge numbers of relatively anonymous people operating under mysterious political malaise. We celebrate the end of a tyrant, but fear what is to replace it.

The decline of the political sovereign and the rise of decentralized power is enjoying popularity in political thought these days. Remember how in 2011 Time magazine named “The Protester” as the person-of-the-year? Aside from the linguistic awkwardness (does that make it “people of the year?” or is it one protester? Who gets to put this on the vita?), Time’s choice highlights some of the difficulty in finding a name and a face for the biggest political actors in our post-national world. Questions like, “Can international law be extended to extra-national organizations like al-Qaida?” and “What’s the difference between a civil war and a rebellion?” trouble the turn of the 21st century. International structures like the Geneva Convention and the United Nations take national sovereignty for granted, but our world is increasing post-national. No longer do we fear the powerful charismatic leader like Hitler, Stalin or even bin Laden, but the widespread networks of people with dangerous convictions, convictions that spread into individual bodies, whose existence as a population rebalances the biopower of the world.

Wait a tick—biopower? This term was coined by Michael Foucault in 1976, not long after the release of Night of the Living Dead, and describes the “numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugations of bodies and the control of populations” (140). The critical term here is, of course, bodies. Biopower describes the most radical divorce of labor from capital, where all that matters is just bodies, and a lot of them. For Foucault, political power came not just in the threat of death to one dissident, but in the definition of what is life. As he wrote, “If genocide is indeed the dream of modern power, this is not because of the recent return to the ancient right to kill; it is because power is situated and exercised at the level of life, the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena of the population” (Foucault 132). Ethnic cleansing does damage to humanity not just because it promotes killing individuals, but also because it erases a group’s influence from the definition of the human race. Genocide seeks to redefine humanity. In a less catastrophic sense, resituating not just individuals within a system, but their contribution to the whole system itself demonstrates the dark capacities of biopower.

So to bring this all back to the living dead, it makes sense that there would be zombie flight attendants, and Ikea employees, and soccer players, because zombie is just a redefining of “the species, the race, and the large-scale phenomena of the population.” What’s scary about zombies in their modern incarnation (no pun intended) is that they aren’t just a threat to humanity, but they are a radical redefinition of humanity, one that sees people not in terms of their physical or educational capital, but only at the basest level—as bodies.

While zombies may be so terrifying for us because they represent a redefinition of humanity, they also represent a scary new responsibility for each individual: removed from the power of a sovereign, how do you know when you’re part of a swarm? If there is no central head and just a powerful cultural milieu, you no longer have the excuse of just having operated under orders. Your actions become both more your own because you are freed from the hierarchal system, and less so, because you have joined with a mass just as unpredictable as yourself. You have bought into something bigger than yourself, that incorporates your body into its purposes. Joshua Gunn and Shaun Treat call this fear “‘the zombie complex’: a fantasy that ideology animates bodies and robs them of agency” (160), but they use the term to describe the unease some scholars have with the theories of determinism. I would argue that this isn’t just an academic anxiety, but a popular one. All across the world, the increasing power of ideology instead of sovereignty has excited a zombie complex. We are uncertain whether this move from hierarchal leadership to the politics of crowds is humanizing or dehumanizing.

Still, despite these lingering societal fears, some scholars describe the end of sovereignty and the rise of decentralized ideology as an uncomplicatedly positive outcome. In Multitude, Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt optimistically refer to the power of the multitude, a group of individuals who are able to act individually and collectively. The multitude is not necessarily united in a political conglomeration, as in “We, the People,” but nonetheless, their individual actions all add up to real political power: “We are thus no longer bound by the old blackmail; the choice is not between sovereignty or anarchy. The power of the multitude [is] to create social relationships [and] thus presents a new possibility for politics” (336). Hardt and Negri’s multitude works collectively to solve problems, like crowd-sourcing faulty code in open-source systems—even when it’s the faulty code of governance. But the multitude remains individual biological beings, bodies. And those bodies can also be weapons.

Hardt and Negri see biopower as the greatest weapon of the multitude. Again, think of the physical presence of bodies in the Occupy Wall Street movement or in the protest camps in Egypt, whose power was just in living, in taking up space in a place and daring others to remove them. Hardt and Negri suggest the multitude’s awesome biopower has accelerated from a long tradition, for example, the sex-withholding pacifists in Lysistrata (347). Bodies organized through a common ideal have power. There will be violence in the multitude’s appropriation of government, even if that violence is defensive and democratic (334-5), and that violence will happen through bodies.

The greatest power that bodies can have, though, isn’t in staging sit-ins or kiss-ins, but in dying. While careful to condemn car bombers, Hardt and Negri describe the enormous power of martyrdom, not just because of its shock, but because of the way it redefines the population surrounding the martyr, because it “testifies to the possibility of a new world” (347). The martyr qua martyr is powerful not because of the convictions it holds, but because of the exploitation of the body to illustrate the possibilities. When ordinary individuals can have remarkable power simply because they live or they die, the contributions of a powerful elite falter. It’s little wonder that the past few decades have seen an increasing fascination in the hordes of undead who possess no weapons, no special talents, no charisma, but simply present their bodies, over and over again, too many to be killed, too persistent to be ignored.

It’s perhaps unfair to suggest that Hardt and Negri are proposing rule by zombie horde. After all, they embrace a sort of Madisonian representation, the ultimate goal of which is “a revolution, aware of the violence of biopower and the structural form of authority to use the constitutional instruments of the republican tradition to destroy sovereignty and establish a democracy from below” (355). But perhaps this is what’s driving all of these zombie-fighting plants and the rise of the zom-rom-com: the fear that the next big threat isn’t a new supervillian, but something that infects us more fundamentally, that changes the nature of our bodies through politics. Once our bodies have the capacity to be weapons, can they ever go back to being just our own bodies or are we forever defined in this new sense of the body politic?

And that leads me to one final point: I don’t think it’s insignificant that the zombie threat is, in the words of my new t-shirt, the zombie apocalypse. This second word is, I think, crucial. There is always a sense in zombie stories that the world is changing, for everyone, forever. Zombies are a plague like those described in the book of Revelation, and they usher in “a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and first earth were passed away” (Authorized King James Bible Rev. 21:1). In this new earth, traditional group prejudices break down—the leaders in the apocalypse are not those who have been previously powerful. For example, the black protagonist in 1968’s NOTLD is able to be the de facto leader of the white survivors, the directionless loser of Shaun of the Dead (2004) is able to become a hero, and in Max Brook’s World War Z (2006), lawyers, movie stars, and politicians become subordinate to working-class folk and military grunts who have more practical abilities for the situation. Again, it’s ambiguous whether this breakdown of society is terrifying or liberating, or, more likely, both. The only group division that matters in this new earth is “us” and “them,” the living and the undead. You never hear about a vampire apocalypse or a ghost apocalypse, but zombies, because they so radically redefine groups of people into populations of bodies, are almost always apocalyptic in contemporary representations.7

The zombie apocalypse is fundamentally typified by the collapse of government. Consider, for example, the moment in The Walking Dead when the CDCs fall or the scene in World War Z (2013) when Brad Pitt’s character, having shot a man while defending his family, cowers from an approaching policeman—who then ignores him to loot supplies for his own family. Later, Pitt witnesses the complete collapse of Israel under the zombie horde. Government organization does eventually bring an orderly dawn in 1968’s Night of the Living Dead, but more recent zombie stories such as The Walking Dead and the 2007 film adaptation of Matheson’s I am Legend leave society entirely in shambles, as individuals, families and tribes revert to smaller-scale, provisional government. In the zombie apocalypse, society collapses, government is helpless and individuals are left to redefine their own organization without the scaffolding that has typically guided our response to threats. And that, as much as anything, may just be what’s so scary about zombie’s redefinition of humanity after all.

Image 4: Portrait of the author as a young zombie.

Mary Hedengren is a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, where she studies the rhetoric of emerging identities. Her research interests include post-transnational identity, nascent disciplinarity and things of that ilk. Mary is the host of the rhetorical history podcast Mere Rhetoric, also available on iTunes. This is not the first time she has produced academic work about zombies, despite a relatively happy childhood.

Notes

1. That once guest starred Margaret Atwood!.↩

2. For more on this, see Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff’s (2002) “Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants and Millenial Capitalism.”↩

3. Romero admits to being inspired by I Am Legend (qtd. Waller 275) and, indeed, if we’re looking for the roots of the leaderless, uncharismatic, scientifically-defined ghoulish horde, we probably ought to start with Matheson’s novel. Romero, like so many great thinkers, is perhaps best honored as a popularizer, in this case of a particular form of monster.↩

4. And you can be one of them. Because of a copyright snafu, NOTLD is within the public domain, which means you can watch the whole dreadful thing here, here, or here. The Library of Congress does include NOTLD in its registry of culturally significant films, but more tellingly, it has been translated in 25 languages, grossed millions of dollars worldwide and kept countless people up at night.↩

5. Yep, it’s absolutely true; Annie Dillard’s dad is in Night of the Living Dead, which gives you a sense of its true indie roots.↩

6. It’s always struck me how similar the very classy and critically-acclaimed Night of the Living Dead is to Ed Wood’s famous B-movie: Plan 9 From Outer Space. In both stories, the dead rise to terrorize the living because of space rays. It goes to show how critical execution is. If you haven’t seen Plan 9, you need to stop reading this article, go watch it and then take some time appreciating the nuances of really bad American cinema.↩

7. There are a few, rare instances of other speculative invasions in recent time that also break down government. War of the Worlds (2005) describes a societal breakdown where society is reduced to basic patriarchy. While I agree that War of the Worlds does border on the apocalyptic for the individual family, government and military organizations are still largely effective. Similarly, the television series Revolution (2012)also imagines the radical transformation of government in a post-electricity setting, complete with resource-grabbing warlords and utopian communes, but still, when it comes to destroying “society as we know it,” it’s hard to beat the zombie apocalypse.↩

Works Cited

28 Days Later. Dir. Danny Boyle. Perf. Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris and Christopher Eccleston. DNA Films, 2003. Film.

Authorized King James Bible. Salt Lake City, UT: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Web. 21 January 2014.

Brooks, Max. World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War. New York: Random House, 2006. Print.

Brummett, Barry. Rhetorical Dimensions of Popular Culture. Tuscaloosa AL: U Alambama P. 1991. Print.

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. Berkeley: U of California P. 1966. Print.

Chalmers, David J. The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. New York: Oxford UP. 1996. Print.

Comaroff, Jean and John Comaroff. “Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants and Millennial Capitalism.” South Atlantic Quarterly. 101.4 (Fall 2002): 779-805. Web. 29 November 2013.

Dillard, R. H. W. Horror Films. New York: Monarch. 1976. Print.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: The Use of Pleasure. Vol. 1. Random House Digital, Inc., 1990. Web. 17 October 2013.

Gunn, Joshua and Sean Treat. “Zombie Trouble: A Propaedeutic on Ideological Subjectification and the Unconscious” Quarterly Journal of Speech. 91.2 (2005): 144-174. Web. 17 October 2013.

Hedengren, Mary. “Not Hitler—Germans: Night of the Living Dead and the Decentralization of Horror.” 2003. Unpublished manuscript.

I am Legend. Dir. Francis Lawrence. Perf. Will Smith, Alice Braga, and Charlie Tahan. Warner Bros, 2007. Film.

Matheson, Richard. I Am Legend. New Work: Rosetta. 2011. Web. 17 October 2013.

Negri, Antonio and Michael Hardt. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin. 2004. Print.

Night of the Living Dead. Dir. George A. Romero. Perf. Duane Jones, Judith O’Dea and Karl Hardman. Image 10, 1968. Film.

“Person of the Year 2011—The Protestor. Time. n.d. Web. 17 November 2013.

Revolt of the Zombies. Dir. Victor Halperin. Perf. Dorothy Stone, Dean Jagger, and Roy D’Arcy. Edward Halperin Productions, 1936. Film.

Revolution. Eric Kripke. Perf. Billy Burke, Tracy Spiridakos and Giancarlo Esposito NBC. Television.

Shaun of the Dead. Dir. Edgar White. Perf. Simon Pegg, Nick Frost, and Kate Ashfield. Rogue Pictures, 2004. Film.

“TS-19.” The Walking Dead. 5 Dec. 2010. AMC. Television.

Waller, Gregory. The Living and the Undead: From Stoker’s Dracula to Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. Urbana, IL:Chicago UP. 1986. Print.

War of the Worlds. Dir. Stephen Spielberg. Perf. Tom Cruise, Dakota Fanning and Tim Robbins. Paramount, 2005. Film.

Webb, Jen and Sam Byrnand. “Some Kind of Virus: The Zombie as Body and as Trope.” Body and Society. 14.2 (2008): 83-98. Web. 29 November 2013.

White Zombie. Dir. Victor Halperin. Perf. Bela Lugosi, Madge Bellamy and Josteph Cawthorn. Edward Halperin Productions, 1932. Film.

World War Z. Dir. Marc Forster. Perf. Brad Pitt, Mireille Enos and Daniella Kertesz. Plan B Films, 2013. Film.