A companion text to a piece of online activist rhetoric, this essay attempts to explain how social media networks and other digital interfaces intercede and influence users' constructions of gender and consumer identity. Gaining awareness of the influence networks have over our lives should empower users to appropriate and subvert those networks for alterior agendas. This essay, and the activism it introduces, demonstrates an appropriation of Pinterest, a "pinboard-style" social media network, for the purposes of subverting and exposing its typical heteronormative and pro-consumer practices.

Technology, like rhetoric, can both push and pull at us. Not only do 'artifacts have politics,' as Langdon Winner has claimed, they also have rhetorics. Technology pushes or manipulates us by requiring us to do certain things and in certain ways…. A technology pulls from us, or panders to us, by reconfirming and strengthening our inclinations and propensities.

— Carolyn Miller

The above epigraph, taken from Miller's foreward to Rhetoric and Technologies: New Directions in Writing and Communication strikes me as an especially poignant way not only to assert the ideological and rhetorical properties of technologies, but, in the process, to deny the idea that technologies might be neutral tools, passively waiting for human users to give them meaning, politics, rhetoric.

Technologies, as Miller writes, are constantly acting on us, engaging us in practices, communities, and media that can never be ideologically neutral. Such technological "sponsorship," to borrow a term from Deborah Brandt, is increasingly evident in the digital spaces and media that now represent a significant part of our social, economic and political lives. Social media networks influence our politics, our financial decisions, our notions of aesthetics, even our ongoing constructions of gender identity. Learning to recognize how social networks accomplish such rhetorical work is becoming significantly more important as these networks become further embedded in our everyday interactions to the point at which they become naturalized. Even more critical, however, is the ability to critique social networks by calling attention to their implicit ideologies.

As a companion text to a piece of online activist rhetoric, this essay demands that we become more conscious of the ways in which social media technologies, and the cultures that emerge around those technologies, are shaping our lives. It does so by examining, in particular, the ways in which the social media network Pinterest, the pinboard-style social photo sharing website, performs rhetorical work on its users' notions of gender identity and directs their consumer behavior. This essay, and the piece of online rhetoric it introduces, wants to demonstrate that we can "queer" a technology by acknowledging and challenging its ideological, political, or rhetorical agenda.

But what would it mean to "queer" a social media application like Pinterest?

As a rhetorical action, such a move would attempt to subvert the application's discursive production of normative identity, not only in terms of gender and sexual orientation, but also across axes of "good" consumer behavior. Is the discourse produced on Pinterest heteronormative? Its largest user demographic is female, and such a demographic is regulated and constructed both within the network itself as well as through other mainstream media outlets. Consider how a Pinterest rep. responds to this Fox Carolina News reporter’s question about the gendered user-base:

We see Pinterest as something that's useful for everyone in the world - male or female. The act of collecting is a universal behavior. People who initially discovered Pinterest were largely women who were pinning for hobbies or activities and they attracted like-minded 'pinners.' However, we believe our demographics will shift over time as more people discover the many different ways in which Pinterest can be used. Just as Facebook initially appealed only to college kids and is now ubiquitous, we believe Pinterest's appeal will evolve to a broader and more demographically diverse audience. (“Is Pinterest Just for Girls?”)

The article goes on to discuss a college course that attempted to explore the gender dynamics of the social network. The professor’s "findings," as represented in the article, demonstrate an incredibly static and reductive stance on gender construction via the website, which allows for a "daydream mentality that may appeal more to female users."

GENDER FUCKING IS...

A genderfuck, or gender fuck or gender-fuck, is the conscious effort to mock or "fuck with" traditional notions of gender identity, gender roles, and gender presentation which assume that one's identity, role and orientation is determined by one's sex assigned at birth. (Wikipedia)Another piece, this time from left-leaning online mag Salon.com, questions the social media network's success in light of recent imitation websites attempting to attract men:

Just last week, Buzzfeed came up with a much-forwarded list of "125 Reasons Why Guys Are Scared of Pinterest" — almost all of which involve scary declarations of man-averse female feelings, a testament to the ways in which Pinterest has not only become emblematic of the gender divide, but a repository for knee-jerk sexism. No wonder then that a host of new Pinterest-inspired, decidedly dudely sites like Dart It Up and Manteresting are springing up in reaction to Pinterest’s Girls Gone Gluegunning vibe. The results have been mixed, though — even with self-aware senses of humor and more cars, bikini girls and red meat than an entire Axe campaign, you can’t just butch up a "pinning" format that is inherently about as studly as a subscription to Real Simple.

And while the author of this article, Mary Elizabeth Williams, sees the web site as participating in gender binary construction, her main interest is in questioning whether or not Pinterest can keep attracting users. Rather than challenging the reductive representations of gender produced by the website as well as outside responses to its success, Williams asks: "As a host of male-centered 'pinning' sites arrive, can the female-centric phenomenon continue its success?"

Beyond the construction of a normative and fixed gender identity, Pinterest is also becoming an influential intermediary in the establishment of "female" consumer trends:

Beginning this summer [2013], Pinterest became the top social referrer for marthastewartweddings.com and marthastewart.com, sending more traffic to both properties than Facebook and Twitter combined. Pinterest is on track to become the second highest traffic driver (after Google) to Cooking Light‘s website, up 6,000% from just six months ago. The social bookmarking site already drives three times the amount of traffic to Cooking Light compared to Facebook (Mashable).

The establishment of these trends, as filtered through the medium of a reductive production of gender and gender binaries via Pinterest, spirals out into other discourses of consumerism. Such a process ultimately has ramifications for the static gendering of all kinds of consumer products and markets.

Queering Pinterest

So what would it mean to queer Pinterest? It would mean a disruption of consumer referrals via displacement of normative gender production. It would mean misappropriation, a transgression of the average norms of discourse produced, shared, and forced into market demographics. It would mean irreverence. Would such a disruption qualify as queer rhetoric as defined by Jonathan Alexander and Jacqueline Rhodes?

Queer rhetoric names a constellation of discursive practices that emerge at different times for different groups in order to articulate resistance to regimes of sexualized normalization. Such strategies seek to remedy the impoverishment of our imaginations, of our sexual and gender imaginary, and to re- introduce into public discourse the imagination of bodies that exceed the normalizations of the juridical, political, medical culture that "fixes" things.

My experiment in digital-rhetorical activism assumes that such a practice is possible, that the "pinning" of queer and anti-consumer images, links, and videos in this online public sphere disrupts the normative discourse produced on the network. And furthermore, that this practice of disruption serves to challenge problematic (and hegemonic) gender constructions that occur in Pinterest. Users can maintain agency over the normalizing and mainstream influences of the social network by realizing that Pinterest is only problematic insomuch that it becomes all-encompassing, what Tammy Oler, blogging for Bitch Magazine, describes as the "pink ghetto that defines what women are passionate about and how they behave online" ("Pinned Down").

The activist pinboard I created to accompany this essay demonstrates this practice as it attempts to call attention to the implicit ideology of Pinterest’s culture-of-use, "the historically sedimented characteristics that accrue to a [computer mediated communication] tool from its everyday use" (Thorne, 40). My attention to the culture of the social network, rather than its actual interface, is not meant to suggest that interfaces themselves aren't ideological, but rather to acknowledge how interfaces also accrue cultural significance and meaning through their users. As Tara L. Conley has acknowledged, "Pinterest users play a primary role in how content is curated across the platform," and those users can promote more diverse, complex, and beneficial ideations of gender by asking the right questions:

Being that we (our bodies, our ideas, our hobbies, our dreams) drive Pinterest, it behooves us to seek out ways to use this platform to enhance our work in improving the lives of cis/women, girls and our allies. That said, however, meaningful content on Pinterest does exist, such as boards that feature topics on feminism, LGBTQ, domestic violence prevention, rape culture awareness, and my personal favorite (although terribly scanty) Gloria Anzaldua. But how might sharing and curating these images via social networks benefit our activism work and civic engagement online and offline? In other words, how can we make Pinterest work for us? (Ms. Magazine Blog)

My pinboard answers Conley's call to "make Pinterest work for us" through conscious rhetorical decisions of naming, pinning, and interaction within the larger Pinterest ecology. My choice of the user alias "Hetero-Consumer Data" calls attention to and challenges the ways in which Pinterest users' information (demographics, consumer behavior, etc.) are often sold to third-party markets, as well as how this data is assumed by these markets to represent heterosexual and cissexual identities. Yet this choice also introduces the pinboard's commitment to an agenda of disidentification, what José Muñoz has described as "recycling and rethinking encoded meaning":

The process of disidentification scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of a cultural text in a fashion that both exposes the encoded message's universalizing and exclusionary machinations and recircuits its workings to account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications. (31)

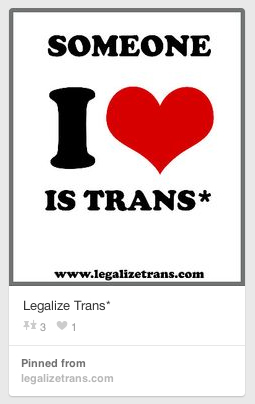

Such "scrambling" and "reconstruction" are furthered in my pinboard, "Queering Pinterest," through the composition of two types of pins that interrogate heteronormativity and consumerism. The most prevalent types of pin on this board are those that bring in new content (images, media, links, etc.) from outside the Pinterest ecology.

This type of pinning disrupts typical manifestations of sexual and gender identity on Pinterest by introducing new content into the network, content that, in the process, also introduces and reinforces new/minority identities and identifications, as in the "Someone I [love] is Trans" pin (above).

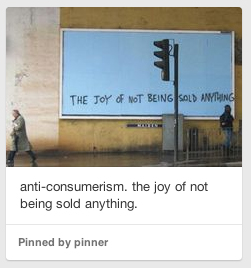

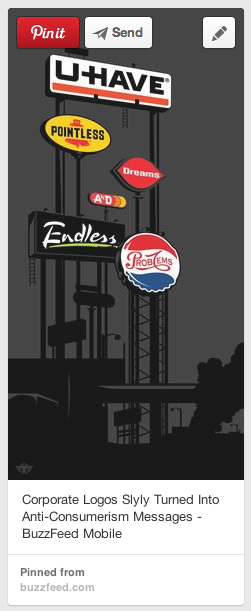

Pinning from the outside is a powerful way to queer the tech; it allows for the disruption of a network from multiple sources beyond its own parameters. Yet, as Conley has noted, there is also a growing contingent of pinners on the network already resisting normative identity production as well as forwarding progressive content that questions the rampant consumerism of late capitalism. Re-pinning such content is another effective way to gain agency over and with/in the network as it allows for the circulation of existing pins and the reinforcement of relationships between users (follows, shares, etc.). The "anti-consumerism" pin (right) is one such pin. Because it was found and shared from another pinboard, it surfaces within the Pinterest network. Yet what makes this example so compelling is that it doesn’t link outside the network either. "The Joy of Not Being Sold Anything" disrupts common consumer traffic-driving practices by not referring traffic, by existing solely as progressive visual rhetoric.

A final strategy for activism demonstrated on this pinboard, one that further illustrates the subversive capabilities of disidentification, is the pinning of visual content that has already undergone the process of culture jamming: the remixing of slogans, advertisements or other propaganda produced by dominant institutions in order to subvert the ideologies those institutions attempt to forward. The example pin, "You Have Pointless Dreams And Endless Problems" (left) shows how visual rhetors remix/jam corporate logos to interrogate corporate advertising.

My experiment in social media activism ultimately seeks to demonstrate how we can appropriate social networks through methods of disidentification in order to expose and subvert heteronormative and pro-consumerist mechanisms. And while I'm working specifically with Pinterest, I also hope to call attention to implicit ideologies of other communicative technologies and digital media. To queer the tech is to realize the ways in which digital tools, and the cultures-of-use that build up around them, are directing our lives. It is also to be empowered to appropriate those tools for our own ends, and for the ends of those silenced and marginalized by mainstream discourse.

For the rhetorical work of this experiment to achieve anything, however, the pinboard must be exposed, added to, and promoted. This is where you come in:

Works Cited

Alexander, Jonathan, and Jacqueline Rhodes. “Queer Rhetoric and the Pleasures of the Archive.” Enculturation 13 (2012).

Conley, Tara L. "The Pinterest Problem." Ms. Blog. Ms. Magazine. 21 May 2012. Web. 19 Mar. 2014.

"Genderfuck." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 4 Nov. 2013. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

Indvik, Lauren. "Pinterest Becomes Top Traffic Driver for Women's Magazines." Mashable. 26 Feb. 2012. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

Miller, Carolyn R. "Foreward: Rhetoric, Technology and the Pushmi-Pullyu." Rhetorics and Technologies: New Directions in Writing and Communication. Ed. Stuart Selber. Columbia, SC: U of South Carolina P, 2010. Print.

Muñoz, José. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1999. Print.

Oler, Tammy. "Pinned Down." Bitch Magazine. Bitch Media. Aug. 2013. Web. 19 Mar. 2014.

Thorne, Steven L. "Artifacts and Cultures-of-Use in Intercultural Communication." Language Learning and Technology 7.2 (2003): 38-67. Print.

Wachter, Dana. "Is Pinterest Just for Girls?" Fox Carolina. 30 May 2012. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.

Williams, Mary Elizabeth. "Pinterest’s Gender Trouble." Salon. 2 May 2012. Web. 27 Nov. 2013.