Super Mom in a Box

Lindsey Harding

"Super Mom in a Box" examines how Pinterest influences identity formation in mothers who interact with the site. In the essay, I use my own extensive interactions on Pinterest to investigate how the site's postfeminist content and interaction design create a hypermaternal identity for maternal interactors. This piece suggests that the celebration of domesticity and femininity on Pinterest validates a mother's home-oriented interests and reinforces her commitment to family; at the same time, this celebration contributes to a limited online identity for mothers, which can produce stress and alienation in real-world experiences of motherhood. In other words, because I’ve scrolled through thousands of pins and repinned hundreds of times, I now wonder, Does my daughter’s birthday party need to be its own version of Disneyland? Are baked goods good enough holiday gifts for neighbors? When did party food start requiring framed labels?

And most importantly, What has pinning done for and done to mothers?

The Power of Pinterest

For almost a year, I was a regular mommy blogger and active Pinterest pinner. Between February 3, 2012 and December 14, 2012, I published over 100 posts on my personal blog The Milk Tree. I started using Pinterest in October 2011, and between then and now, I have amassed over 1,400 pins organized on 35 boards.

What I wrote about on my blog often reflected my interactions with Pinterest. When our family wasn’t doing a holiday photo shoot with oversized tree ornaments in our yard, when I wasn’t scoring eleven clothing items and a toy from a consignment sale for $13.75, I turned to Pinterest to build my blog—with pictures, lists, craft projects, and more.

Fig. 1. Sample pin. Pins feature

two parts: pin data (image,

comment, and number of likes

and repins) and interactor data

(profile image, name, and board title).

Image from Pinterest.

This meant, of course, Pinterest was responsible for a lot of my life: the food I made, the family activities we did. Pinterest is a social media site that acts as a giant digital bulletin board to collect and organize inspiring, helpful, and just plain cool content.

Its two fundamental components are pins, which are defined on the site as “visual bookmarks for good stuff you find anywhere around the web or right on Pinterest,” and boards, “where you collect Pins by theme or topic” (“About Pinterest”). According to David Harper, “[i]t is a new, visually-centered performance space that encourages self-representation primarily through images.”

After my children went to sleep, I’d spend hours some nights scrolling through pins (Fig. 1), and I went to sleep feeling like a better mom even though I hadn’t done anything for my kids.

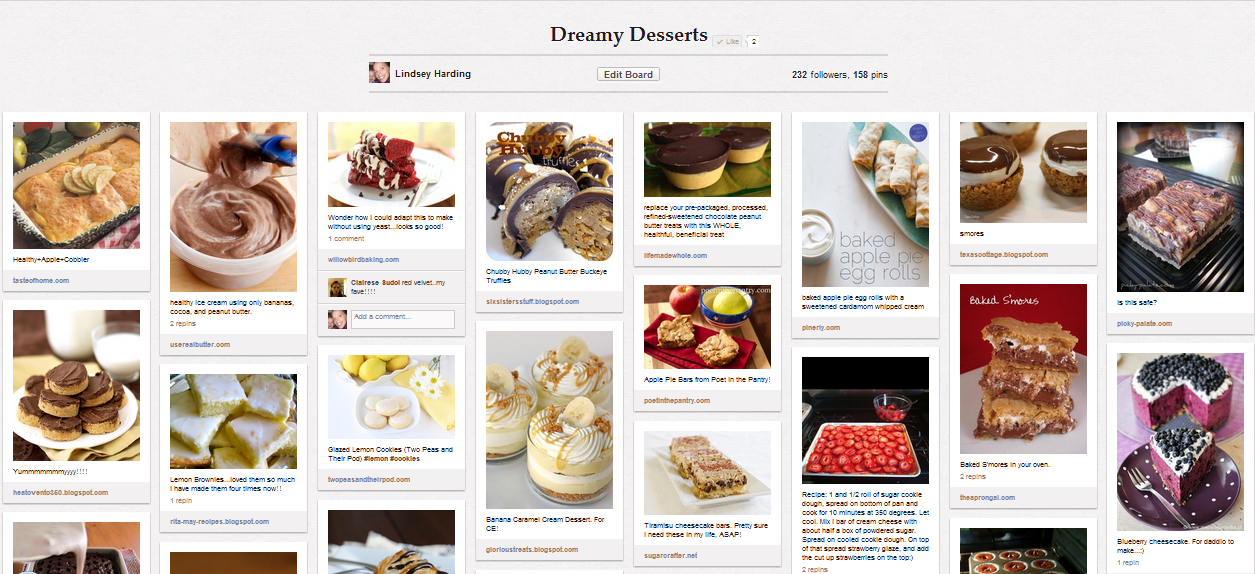

I found plenty I could do. I created complete virtual childhoods on boards populated with motor-skill-enriching holiday projects like M&M wreaths, upcycled pallet toddler beds, and 34 different types of peanut buttery desserts (Fig. 2). That felt like enough.

At the same time, I had been reading Richard Lanham’s The Economics of Attention, and I was sensitive to the scarcity of my attention in light of myriad demands for it scattered between offline and online, professional and personal activities and responsibilities. Though I was hesitant to acknowledge it, I sensed that my pinning amounted only to the illusion of maternal productivity. What’s more, I knew at some level that pinning was a distraction, a way of avoiding the tedious labors of home maintenance and the coursework I should have been doing.

Finally I became saturated and then overwhelmed with pins, with just the ideas of recipes and activities and projects. I stopped pinning. Instead, I wondered how Pinterest had become such a powerful presence in my life and in my emotional satisfaction as a mother. To understand this, I knew I would have to look at Pinterest differently. Instead of Inspiration Hub for mothers, I considered Pinterest as a website, an instance of digital media. In the process, Pinterest changed for me, and I changed as a mother.

Fig. 2. Sample board. Boards categorize and contain pins.

Users are given a set of pre-titled boards when they join

Pinterest, but they can create as many new boards as they

need or desire to organize their pins. Image from Pinterest.

Pinterest blends the delight of immersive discovery and exploration with a strong sense of agency. This is the source of the site’s power, its ability to satisfy users in a way that feels very, very real. Pinterest offers an “immersive environment…one that captivates and holds our interest because it feels expansive, detailed, and complete” (Murray 102).

As Bonnie Stewart points out, what we do in this sort of environment has important consequences for our identities: “Because make no mistake: the way social media works, our Pinterest practices ARE shaping our digital identities.” How Pinterest captures the attention of mothers through the curation and appropriation of domestic content means that the site does more than captivate mothers; it contains them, locking them into a series of behaviors and a single maternal identity: mother as domestic housewife.

This identity is supported by a postfeminist cultural landscape that has gone digital and turned aesthetic value into “real value in the current cultural marketplace” (Negra 152).

Using Diane Negra’s discussion of postfeminism as a backdrop, I propose that Pinterest extends the “domestic dream narrative that proliferated in the late 1990s/2000s” with its emphasis on “perfectionist domesticity and new discourses of ‘homemaker chic’” and makes it more accessible, more participatory, more praiseworthy (152). Negra argues that “postfeminism is consistently associated with a design for living that is deeply traditionalist and that centralizes a female homemaker figure” (152). On Pinterest, interactors are invited to partake in this design, to see and engage with “sumptuous domestic scenes” as well as the “assumption that women remain uniquely responsible for the conditions of family life” as they bookmark and consume content involving food, family, and the home (Negra 152).

Regardless of who I was away from the screen, then, my interactions with Pinterest pulled me into “the omnipresence of postfeminist identity paradigms” and defined me according to hyperdomestic, hyperfeminine, and hypermaternal responsibilities, values, and concerns (Negra 5). On Pinterest, I found monthly and seasonal cleaning plans. I learned at least 101 indoor activities for kids. I discovered new crockpot recipes and life binders. The site encouraged my efforts with closet organization. Ultimately, I realized a world of maternal, domestic, and feminine ideas I had never before considered. Pinterest showed me that world; at the same time, it gave me a chance to celebrate and share my own successes with my house and children.

But as a Ph.D. student at the University of Georgia, I spent the bulk of the workweek away from my children, away from the house, teaching and studying on campus. Pinterest didn’t care about my seminar paper, short story, or syllabus; instead, it valued the ingredients I used to prepare dinner, the routine I implemented to get my children up and out the door in the morning, and the candle-holder I repurposed into a key and change organizer for our kitchen (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Picture I pinned to Pinterest

from

my blog with the following

comment:

"Tin candle-holder turned

into a key and

change organizer

with the addition of a

door knob

and hook!" Image from my

personal collection.

Sherry Turkle suggests, “When part of your life is lived in virtual places…a vexed relationship develops between what is true and what is "’true here’" (153). I felt this tension acutely, and in what follows, I propose that this vexed relationship amplifies the “deep uncertainty postfeminism implies about what it really means to live as an adult woman in early twenty-first century America” (Negra 14).

Pinterest both participates in and offers an escape from such ambiguity. Rob Horning argues, “Literal digital appropriation becomes a means to generating a sense of orientation in a culture in which everything that is solid melts into air and all that.” Instead of confronting ambiguity and uncertainty directly, Pinterest lets us remain “inebriated on images; we keep busy pinning things” (Horning). Though Horning suggests the fervor of pinning and inundation of images ultimately “multiplies the instability of meaning,” I argue that these conditions enable meaning to be abstracted into a simplified representation that precludes messy, uncomfortable contradictions.

That is, I came to feel like a crafty mom by pinning DIY projects to my Craft Ideas board even though I didn’t even own a glue gun. My online, social “performances of identity” came to “feel like identity itself” (Turkle 12). Pinterest put me in a box captioned “confident, creative mother.”

And yet in using Pinterest to innovate, motivate, and organize, I found I was undermining the pleasure of my real-world experiences. I discovered that I was altering my identity so I could be seen by other moms and myself as a certain kind of mother, a mother who despite her good intentions is spread impossibly thin and handcuffed to the hearth.

Turkle asserts, “Technologies, in every generation, present opportunities to reflect on our values and direction” (Turkle 19). In this piece, I hope to make visible what Pinterest reveals about maternal values and activities in the digital age by focusing on the site’s postfeminist content and rhetorical mechanisms. Ultimately, I will show the constraints Pinterest places on interactors’ identities and the real-world consequences of those constraints for individual mothers and maternal culture today.

Pinterest as Tupperware Party

The appeal of participating in Pinterest’s container-based organizational system is reminiscent of Tupperware’s allure for women in post-WWII America. In Tupperware! The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America, Alison J. Clarke discusses the role Tupperware parties played in women’s lives at that time. A social phenomenon with roots in sewing circles and quilting bees dating back to the 1820s, “the Tupperware version of the hostess party acted as a celebratory and consciously feminine activity” (Clarke 107).

Social participation on Pinterest engages interactors in the same sort of activity. I joined countless users in celebrating and repinning pins for cleaning baseboards with dryer sheets and high, glittery heels (Fig. 4). Clarke also describes the emergent benefits of Tupperware parties, which are available on Pinterest, as well.

Fig. 4. These screenshots highlight Pinterest celebrations of domestic

and feminine

content as evidenced by pin statistics. In the first one,

a household tip pin for using

dryer sheets to clean baseboards amassed

7451 repins and 540 likes. The second

one shows information and

comments for a glittery high heels pin, which gathered

3,481 repins

and 1,184 likes. Images from Pinterest.

Just like her 1950s predecessor, a woman using Pinterest can “improve her knowledge of household economy, by benefiting from novel recipes and homemaking tips” (Clarke 107). On Pinterest, these gains become the catalyst for social interaction. While Tupperware “saleswomen made their own contribution to sociability and information exchange,” Pinterest users turn this contribution into the main act, the point.

In a way, Pinterest enables all women to become Tupperware saleswomen, and digital media removes the need to have any product at all. Instead, virtual containers are pushed, praised, and gathered around. The Tupperware slogan Clarke references—“a modern way to shop for your houseware needs, conveniently, leisurely, economically” (112-3)– could serve Pinterest well, with shopping abstracted to scrolling and houseware needs abstracted to ideas presented in little boxes.

Fig. 5. Stills from a 1960’s Tupperware commercial featuring living

room party scenes. Images from the Prelinger Archives.

Further, Clarke’s depiction of the Tupperware party as an interactive gathering seems a suitable portrayal of Pinterest: “a forum that melded modern manners, new consumer products, and contemporary recipes” (116) (Fig. 5). Just as women on Pinterest are encouraged to pin, comment, and curate their own boards, “Women were encouraged to offer their interpretations of particular items, swapping homemaking advice and contributing to the formal design process” (Clarke 116). The activities and expectations that characterize the Tupperware party are updated and remediated in the digitized postfeminism espoused on and by Pinterest.

The Rhetorical Work of Pinterest’s Design

On the one hand, Pinterest creates a community of women who define motherhood as a praise-, time-, and attention-worthy public endeavor; on the other hand, it shrinks that community to a single user: the Pinterest Mom. This generic, default digital identity is brought about from the rhetorical mechanisms supported by the site’s interaction design: appropriation and curation. According to Harper, when interactors pin and repin, they appropriate and recontextualize visual content from around the web and Pinterest itself. As a result, “images that once formed part of our composite self-image drift across the landscape of Pinterest and the web, providing someone else raw material to use as they fashion their own self.” Here, Harper calls attention to the way Pinterest supports identity development based on a shared set of public materials.

For maternal users, this reservoir teems with postfeminist identity paradigms abstracted into images and collapsed into Pinterest’s little boxes. Through curation, interactors cobble these boxes together to construct their digital identity. Stewart suggests that curation has cultural capital on Pinterest, which in turn, “identity-wise,” turns us into “consumers, and consumers alone,” who scroll endlessly through images of chore charts and bacon-wrapped finger foods.

But becoming image appropriators, curators, and ultimately consumers on Pinterest has real-world consequences for mothers. For as Stewart argues, “online practices become habits. What we see shared shapes what we understand to be shareable, to be palatable.” The Pinterest Mom may feel validated, empowered, and motivated by the images shared on the site, the domestic inspiration flooding her computer screen; at the same time, what she sees there influences her appraisal of offline experiences. If lived moments are not pinnable, what are they worth? What do they mean?

Downloading Motherhood

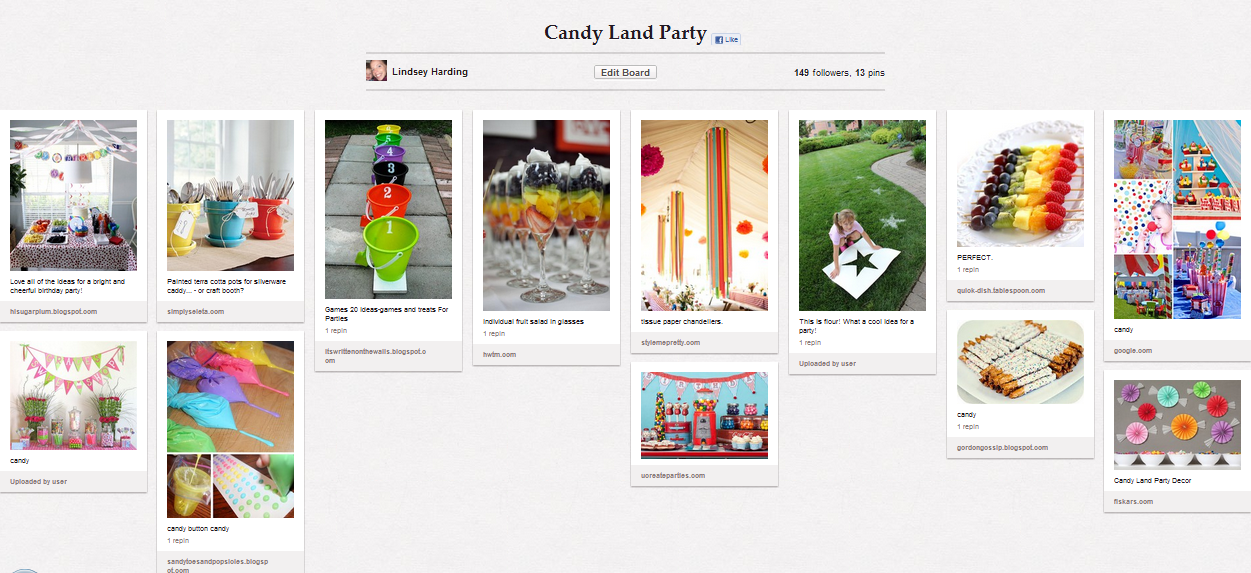

Prior to my daughter’s fourth birthday party on Saturday, April 7, 2012, I scanned and searched Pinterest for theme inspiration. In the middle of March, I showed Riley the Pinterest board I had created for birthdays. We looked at cakes covered with M&Ms and giant lollipops constructed out of wrapping paper rolls, balloons, and cellophane (Fig. 6). Together, our minds filled with clever rainbowy party ideas; we decided on Candy Land as the theme. We were both excited: Riley loves candy, and I had Pinterest to help me design and execute a sugary world of birthday fun.

Fig. 6. Giant lollipops pin. This is one of the key

images that inspired my daughter's Candy-Land

-themed birthday party. Image from Pinterest.

That night I created a new board titled Candy Land Party on Pinterest (Fig. 7). I started amassing images of colorful decorations and candy-themed favors and food. Soon I had 13 pins to add to the 38 pins on my Birthday board. Meanwhile, Riley’s party crept closer. I reserved a pavilion at a nearby park. I bought invitations from Target. My husband and I brainstormed ideas for games and activities to entertain a small herd of preschoolers. Plans, though mostly virtual, seemed to be coming together.

But when we passed out invitations two weeks before the party, I started to feel overwhelmed. I went through my pins and followed the links back to the source mom blogs. I estimated costs. I considered how much time I would need to create giant lollipops, bake and decorate cookie cakes to look like peppermint candies, shop for supplies, coordinate a life-sized version of Candy Land for the kids to play, and develop whimsical themed decor. I couldn’t just buy decorations, could I? Especially not after the Rapunzel party we had attended a few weeks before, a party at which Pinterest—and all the mothers who pinned Rapunzel-related birthday party ideas—seemed like virtual guests.

Fig. 7. Candy Land Party board, where I started collecting pins to help

design and

plan my daughter's party. Image from Pinterest.

Suddenly, it was all too much, and I was still at my computer. I faced too many ways to arrange balloons and snack tables, too many options for serving fruit, and too many uses for tissue paper. Pinning, I realized, was too easy. Online, I had only to enter a visually stunning, classy, and creative Candy-Land-Party world. Offline, the fairytale required time and money I just did not have.

In the end, I pulled off a festive birthday party at the park with lots of candy. I incorporated ideas from three pins, games we had played at Riley’s third birthday party, and decorations I had purchased at Dollar Tree (Fig. 8). I served fruit in bowls.

Fig. 8. My humble attempts to implement pins. The top

picture captures the cookie cakes I made from store-

bought cookie dough. The second image captures the

Dollar Tree plastic tablecloths I used as pavilion

decorations. Images from my personal collection.

Was the party a success? For my daughter and all of the guests, I think so. The two hours passed quickly, the time happy and sweet (Fig. 9).

But for me, I have to admit I was disappointed. Turkle captures the essence of my experience when she writes of time spent online that “moments of more may leave us with lives of less” (154). Compared to my multitude of pins, the overwhelming more of Pinterest, my decorations looked bland, maybe a little tired. My cookie cakes were cute, not breathtaking. My snack table did not have a backdrop. I did not even make the giant lollipops.

Riley might not have noticed the party’s deficiencies, but I did. Negra also helps explain the inadequacy I felt. She highlights “the power of a well-kept home and well-kept body as the new indices of achieved adult femininity in America” (118). To this, I would add a well-executed birthday party.

Unpinned

Fig. 9. An unpinnable moment: Riley

enjoying some candy at her party.

Image from my personal collection.

Now I have been off Pinterest for some time, except for fleeting returns or specific searches, like when Riley wanted to make a pirate treasure chest for a kindergarten project. I haven’t blogged about motherhood for over a year. When I made a pumpkin pie with my two youngest children last November, we used the recipe off the can of pumpkin and unrolled a refrigerated Pillsbury piecrust.

Pinterest may seem to produce more innovative, more productive mothers, but the site eliminates the messiness of mothers figuring out motherhood on their own. In the words of Nicholas Carr who writes about the Internet more generally and its effect on our brains, “[w]hat [is] lost along with the messiness [is] personal initiative, creativity, and whim. Conscious craft [turns] into unconscious routine” (218). While craft tutorials abound on Pinterest, craftiness, that quality that extends beyond a woman’s interaction with mason jars and into the constant on-the-fly thinking required of mothers, is diluted.

I wanted to believe that Pinterest made me a better mom, capable of raising smart, active, and thoughtful children while maintaining a clean, stylish home, all while working, writing, and studying for my Ph.D. After all, Pinterest gave me the gifts of agency and immersion. It encouraged “perfectionist domesticity” and made me believe I could have it all– at least online (Negra 152). But these delights, this fantasy, come with costs. I can see that now.

As mothers amass more and more pins, they become online pack rats; they bring pinned ideas into their lives and pin images from their own lives to their boards. Before they know it, they have 35 boards filled with over 1,400 pins, just like I do, their very own “simple, Stepford-wife simulated reality” (Stewart). Turkle warns that when “immersed in simulation, it can be hard to remember all that lies beyond it or even to acknowledge that everything is not captured by it” (285). Buried under the weight of pins, mothers may forget.

Carr points out that digital technologies require “a sensitivity to what’s lost as well as what’s gained” (212). Thanks to Pinterest, I can cook oatmeal in countless ways. I can initiate “new” birthday traditions. Most importantly, I am validated in my desires to be a creative, organized, DIYing mother even as I pursue a writing and teaching career outside the home. On Pinterest, I become super mom.

This networked mother has an alluring identity. Turkle writes, “online you’re slim, rich, and buffed up, and you feel you have more opportunities than in the real world” (12). I like the giddiness that accompanies the opportunities Pinterest presents to make motherly wisdom mine. I like the power Pinterest offers me to contain and build on that wisdom. There is, in fact, so much for a mother to like about Pinterest. What mother wouldn’t want to be super mom?

But Turkle cautions that engagement in virtual worlds means “there's got to be someplace you're not” (12). For mothers, for me, that some other place involves small children who do not care if the picnic tables at their birthday parties have centerpieces. And perhaps more than time and more than real world pleasure, with Pinterest I lose my maternal instinct to recognize the value of unplanned moments to make memories that cannot ever be reduced to a pin.Lindsey Harding is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia and the Assistant to the Director of UGA's Writing Intensive Program. As a rhetoric and composition scholar, she has designed and published research that investigates the intersection of digital technologies and language use. She’s currently editing her dissertation, which is a multigenre, multimodal collection on domestic digital photography and motherhood in the 21st century. You can find her online at www.lindseymharding.com.

References

“About Pinterest.” Pinterest. Pinterest, 2014. Web. 1 May 2014.

Carr, Nicholas. The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. New York: Norton, 2011. Print.

Clarke, Alison J. Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 20 Apr. 2012.

Harper, David A. "Pinterest and Panopticon: Self-representation Through Appropriation.” viz. Digital Writing and Research Lab, 7 Apr. 2012. Web. 30 Apr. 2014.

Horning, Rob. “Pinterest and the acquisitive gaze.” The New Inquiry. The New Inquiry, 5 Mar. 2012. Web. 1 May 2014.

Murray, Janet H. Inventing the Medium: Principles of Interaction Design as a Cultural Practice. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012. Print.

Negra, Diane. What a Girl Wants? Fantasizing the Reclamation of Self in Postfeminism. New York: Routledge, 2009. Print.

Stewart, Bonnie. “Pinterest: digital identity, Stepford Wives edition.” the theoryblog. N.p., 29 Feb. 2012. Web. 1 May 2014.

“Tupperware Commercial 3.” Prelinger Archives. Internet Archive, 2001. Thumbnail images. Web. 23 May 2014.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011. Print.