Putting Our Bodies on the Line: Towards a Capacious Vision of Digital Activism

Guest Editors: Ben McCorkle & Jason Palmeri

Whenever we go to rhetoric and composition conferences, we often are delighted by the many presentations we see about the implications of employing emerging digital technologies (twitter, Pinterest, GitHub, etc.) to argue for social change. Yet, too often, these presentations are ephemeral—either never published or published years after the fact when they are no longer as timely as they once were. At the same time, in our reading of popular magazines and blogs, we also see many timely and accessible analyses of digital activist campaigns—but too often these popular press accounts ignore important questions of rhetoric, agency, and power.

In this special of Harlot, we seek to provide a timely public forum for rhetoricians to theorize and practice digital activism for broad audiences. In the punk rock spirit of Harlot, we have worked to invite and support rhetorical scholarship that fucks shit up—scholarship that challenges traditional perspectives and scholarly forms to radically enact activism within the field of rhetoric and beyond. In their own distinctive ways, each one of the contributors puts their bodies on the line and challenges us to rethink how we conceptualize and practice digital activism. Although each of the contributions to this issue offers a unique perspective on diverse sites of activist rhetoric, we see some common threads woven across the whole issue.

As Angela Haas has argued, the concept of digital refers as much to the work of the human hand as it does binary code. Even when digital tools enable activists to collaborate across great distances, the body remains a powerful force in the activist scene. After all, we must remember that the web is not and has not ever been a democratic, egalitarian space; power inequalities of sexuality, race, class, gender, ability, and nation persist—and are often reinforced—in online spaces.

Highlighting the ways in which inequalities among women may be reproduced in online activist spaces, Jessica Ouellette’s contribution offers an incisive critique of the feminist blog “Gender Across Borders”—demonstrating how the language of many supposedly “transnational” feminist sites problematically marginalizes the unique embodied perspectives and agencies of women located in the Global South. Similarly revealing how seemingly “open” new media platforms may actually reproduce conservative power dynamics, Matthew Vetter’s contribution powerfully challenges the ways in which users of the social network Pinterest often reinforce normative visions of gender, sexuality, and capitalist consumption.

In the end, the contributors to this issue powerfully remind us that the body is one of the most important activist media that we have—that truly transformative digital activists must seek not to erase the body but rather to address questions of difference and privilege head on.

Rhetoric is first and foremost a productive art. We can’t really analyze well what other digital activists are doing unless we have experience harnessing digital tools for activist purposes ourselves. And, if we rhetoricians wish to have an influence on the broader digital activist conversation beyond the ivory tower, we need to push past the conventional form of the scholarly article to embrace the use of popular multimodal genres for rhetorical intervention.

In this issue, Dustin Edwards enacts digital activist rhetoric by presenting a video remix, "Playing with Plagiarism," that humorously and incisively parodies the simplistic, binary representations of plagiarism that are common in popular media. Arguing that print-based scholarship is not sufficient to combat damaging cultural representation of plagiarism, Edwards calls on rhetorical scholars to employ video composing and other multimodal tools to offer alternative visual representations of ethical source use that challenge dominant conceptions. Further demonstrating multimodal remix as an activist scholarly strategy, Matthew Vetter crafts a queer pinboard that challenges dominant visions of gender and sexuality on Pinterest—vividly revealing how the collection and arrangement of queer digital artifacts can be a powerful activist act. Importantly, Vetter invites us all to contribute to the project of queer world-making on Pinterest, and we hope many of the readers of this issue will choose do so.

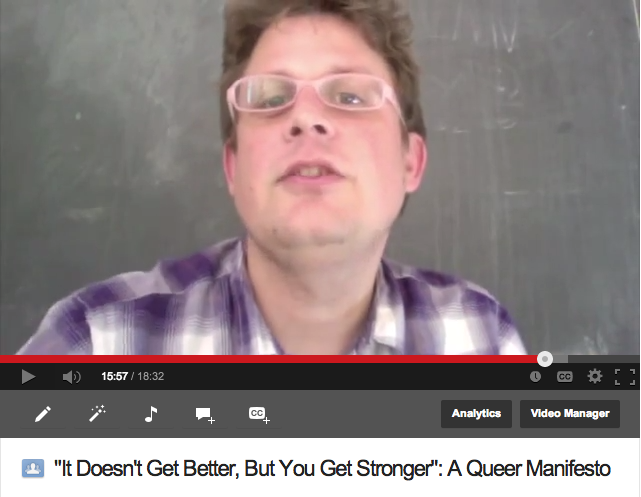

In another example of queer activist practice, Hillery Glasby’s "Let Me Queer My Throat" offers an insightful reflection on the personal and political implications of her own upcoming same-sex marriage—powerfully revealing the complex ambivalence many queer subjects feel when making the choice to assert their own personal right to participate in the problematic institution of marriage. By foregrounding queer ambivalence as an activist tactic, Glasby reminds us that digital activism is not just a process of using digital tools to convey a "coherent message" to a target audience. For Glasby (and for us), queer digital activism ultimately entails resisting simplistic answers, embracing ambivalence as site of knowledge making, and recognizing that our everyday intimate lives are shot through with important and troubling political decisions that cannot easily be reduced to soundbites.

When we put out the call for the special issue, our examples of digital activism were pretty predictable and expected: the use of twitter in the Egyptian revolution, coordinated acts of hacktivism during the anti-SOPA movement, the role of GitHub in the Occupy protests, the use of social media by Pussy Riot, and so forth. Like many digital rhetoricians, we unconsciously found ourselves looking first to the shiniest tools flashing across our screens when we conceived of what digital activism meant. But, as we review this special issue, we are delighted to see that a more capacious vision of digital activism has emerged from the collective dialogue we showcase here.

As this special issue reveals, digital activism can be found in such diverse rhetorical sites as a feminist blog, a trans* image circulating on the web, a line of hacker code, an intimate conversation among queer lovers, a comedic video remix, a sit down strike on campus. When we open up our conceptions of what both “digital” and “activism” mean, we can become more attentive to the complex ways that communication technologies both enable and constrain possibilities for transformative social action. And when we open up our conceptions of what the scholarship of digital activism entails, we just might be able to do a better job of fucking shit up in the field of rhetoric—and in the world at large.

Ben McCorkle, Associate Professor of English at The Ohio State University-Marion and the author of Rhetorical Delivery as Technological Discourse: A Cross-Historical Study, has long been interested in the effects of technological disruption on social and cultural structures—even back in the day when he was a quasi-gutter punk hanging out with the Foods Not Bombs kids in Athens, Georgia, designing Xerox flyers, mixing up batches of wheat paste, and filling five-gallon buckets full of hearty vegan goulash.

Jason Palmeri, Associate Professor of English at Miami University and author of Remixing Composition: A History of Multimodal Writing Pedagogy, is currently researching and practicing online video activism in queer counterpublics. As a Florida high school student in the early ‘90s, Jason once encircled Jeb Bush yelling, "Racist, Sexist, Anti-gay... Jeb Bush Go Away!" Sadly, this moment was not captured on digital media.