Death: The End We All Have to Face(book)

Christine Martorana

When my friend Aaron unexpectedly died several years ago, I gained firsthand experience with a growing online phenomenon: mourners turning to online spaces following the death of a loved one. In what follows, I present details from Aaron's Facebook page in order to illustrate two specific observations: 1) Digital technologies are reconfiguring the permanence of death, inviting the living to recreate the deceased as a heavenly intermediary, and 2) this continued virtual existence of the deceased alongside the constant accessibility of digital technologies is opening a space for death-related egocentrism.

As I have observed Aaron’s wall over the past several years, I have at times admittedly felt like a voyeur observing the unaware. Although Aaron had, by becoming my Facebook friend, granted me permission to see his wall, I am aware that I am observing sensitive and intimate expressions I would not otherwise see. I strive to remain cognizant of the fact that Aaron is not just a Facebook profile; he is someone’s son, brother, and friend. He was my friend. I hope the measures I have taken to respect Aaron’s memory, identity, and those of his family and friends communicate this awareness.

Aaron has 616 Facebook friends. His profile picture is a close-up of his face, eyebrows slightly furrowed, sunglasses resting atop his head. A quick scroll through his Facebook photos reveals his active social life and love for the outdoors. His Facebook wall contains countless posts from friends and family featuring message, photos, and videos. Aaron’s Facebook page appears typical; however, a closer look reveals that although Aaron’s friends continue to post messages to him, Aaron has not responded to these messages in more than five years. This is because Aaron unexpectedly passed away in 2008—and yet, his Facebook page remains active.1

Aaron’s Facebook page is an example of a growing phenomenon: mourners turning to online spaces following the death of a loved one.2 In the face of death, everything from blogs to YouTube series, Instagram feeds, and Tumblr pages are emerging, “bringing the conversation about bereavement and the deceased into a very public forum. [Users] seem eager for spaces to express not just the good stuff that litters everyone’s Facebook newsfeed, but also the painful” (Seligson). After Aaron’s passing, I became one of these online users.

Image courtesy of Maria Elena on flickr.

Aaron and I met three years prior to his death. We’d grown up in the same area and worked together at a part-time job. Although I was about three years his senior, we were part of the first generation of high school students to join Facebook.3 Accordingly, Aaron and I were both co-workers and Facebook friends. When I heard of Aaron’s death, I was, like everyone else, shocked.

Several days later, I looked up Aaron’s Facebook page. Although I never posted there myself, I became engulfed in the flood of posts after his death. As his Facebook friend, I was privy to read these posts and witness the ways in which his close family and friends were using his wall to grapple with their sudden loss. I continued to periodically look in on Aaron’s page, and as time progressed, I was struck by both the heavy, ongoing volume of posts as well as some trends in their content.

Dying in a Digital Age

Digital technologies have seeped into practically every aspect of our lives: eating, sleeping, exercising, driving, shopping, dating, entertainment—and now, dying. As USA Today writer Laura Petrecca notes, we are living in the age of “Mourning 2.0,” where digital technology is inseparable from grieving, forever changing the ways in which we cope with lost loved ones. Grieving, which used to be “private and personal” (Farber 6), now regularly occurs online. Aaron’s Facebook page provides evidence that this is indeed true: “Mourning 2.0” is in full swing.

His page not only demonstrates our “ability to instantly congregate, at least virtually, and commiserate” (Brondou), it also supports two valuable claims regarding this age of digital mourning. First, digital technologies are reconfiguring the permanence of death, inviting the living to recreate the deceased as a heavenly intermediary—a being with access to both our physical world and a heavenly world beyond. Second, this continued virtual existence of the deceased alongside the constant accessibility of digital technologies is opening a space for death-related egocentrism—a self-serving attitude that shifts responses to death from mourning loss to requesting help.

Not Physically Here, But Still Present

The vast majority of us—73% according to Pew Internet Research—lead both physical and virtual lives. This impacts not only how we live from day to day4 but also our experiences with death. For although we might stand graveside and bid farewell to a loved one, we can later stand with our digital technologies and access that person’s social media profile. From this perspective, death is a force with the power to remove our physical bodies yet unable to eliminate our virtual ones.

My experiences with Aaron and his Facebook page testify to this. Although I have not seen Aaron’s physical body in more than five years, I see his face on a regular basis. With just a few keystrokes, I can pull up his profile picture, the same picture that has been there since the day he passed away. This photo, with its static, fixed quality, seems to freeze time, maintaining a visual representation of Aaron as he was while physically alive. When I look at his Facebook page, I see the same teenage boy I remember; as he looks back at me from the computer screen, it is as if he continues to exist virtually despite his physical passing.

This is not to say that others or I fail to recognize that Aaron has physically died. However, because Aaron’s photo has remained unaffected by his physical death, it does suggest that physical death did not lead to a complete and total end to his existence. Instead, Aaron retains a presence on his Facebook page, an observation that echoes Susan Sontag’s claim that, after an “event has ended, the picture will still exist, conferring on the event a kind of immortality” (11). Although Sontag wrote these words in 1973, long before Facebook entered our lives, the concept still rings true: photographs capture and preserve what might otherwise be lost with the passage of time.

What Sontag may have not been able to predict was the impact of the digital photograph. Through digital photos, we can not only capture and preserve moments, but we can also widely distribute and circulate them. Thus, whereas a print photo of Aaron might have previously remained only among close family and friends, today, the digital image circulates among a much larger public of family, friends, and acquaintances connected to one another by Aaron’s Facebook page, unconstrained by the limitations of time and space.

My Digital Guardian Angel

The digital platform not only changes the reach and longevity of the photograph, but it also impacts our grieving process. According to Dr. April Hames, there are six stages of healthy grief: acknowledgement of loss, reaction to loss, recollection of the departed, relinquishing attachments, readjusting, and reinvesting. My observations of Aaron’s page suggest the fourth stage, relinquishing attachments, is complicated by Facebook. That is, since we can often access Facebook pages even after Facebook users have passed away, this digital platform offers a new method of grieving, one that does not require relinquishment.

Specifically, the Facebook users I observed, rather than relinquishing attachments to Aaron, have evolved their attachments to Aaron so that they come to view him as an intercessor between this physical world and another cosmic, divine space. This is evidenced in posts like these:5

- “I GOT INTO MICHIGAN YESTERDAY! omg Im still soo excited.. tell God I said thanks for getting me in cuz I know he had his hand in that.”

- “so it was snowing this mornign and i definately think it had something to do with you becuase you would have been BOUNCING off teh walls at the first snow. haha. so it made me smile. ps. you think you could work out a snow day sometime soon??”

- “please watch over us all during this holiday season & maybe you talk the Big man into some snow? because this rain simply will not do.”

- “Lots of people need prayers and watching over…I know you’re the invisible hero in action…the angel of our prayers…thanks.”

Through these posts, we can see how Aaron’s virtual presence continues as well as how living Facebook users communicate directly with Aaron in the same way they might offer a prayer to a divine being. That is, instead of letting go of their attachments to Aaron, they have evolved these attachments so that Aaron moves from a lost loved one to an available intermediary, one who can communicate with God, control the weather, and hear prayers.

I am not the first to consider the impact of the digital on grieving. Robert Dobler offers a related discussion of grief as it manifests on the social networking site MySpace. According to Dobler’s analysis of MySpace pages of the departed, MySpace users post “personal expressions of grief’ [in an] attempt to mitigate the permanence of the loss by keeping up a direct correspondence with the departed” (176). I have found similar practices on Facebook; both social media sites offer a space in which users can construct new relationships with the deceased, evolving their attachments instead of relinquishing them.

However, whereas Dobler’s analysis leads him to characterize the deceased as a “ghost” (185), my observations suggest otherwise. A ghost implies a haunting, restless spirit; however, the posts on Aaron’s wall do not cast Aaron as either haunting or restless. Rather, a more appropriate image might be that of a guardian angel, what one of Aaron’s friends calls “the invisible hero in action”—a comforting intercessor watching over the living, providing services and guidance as needed and requested.

Mourners left gifts and tributes outside of

Amy Winehouse's home

in London

following her death in 2011.

Image by Gruenemann, Wikimedia

Regardless of whether we think of the departed as ghosts or guarding angels, one thing is clear: the Internet offers multiple avenues for continued interactions with the deceased and their communities. These available avenues take several forms, including online memorials such as Virtual Memorial Garden, a site where mourners create digital photo memorials for lost loved ones, and the World Wide Cemetery, an online cemetery that invites mourners to create virtual monuments in memory of those lost. However, what I have observed on Aaron’s Facebook page offers a slightly different conception of death in this digital age.

These Facebook interactions are taking place at an online site previously inhabited by the deceased, the Facebook page, not at one created in response to the death. We might think of this as a practice similar to “memorials erected at homes of suddenly dead celebrities” (Doss 66). Considered in this light, these Facebook posts reveal our conception of Facebook as a site of lived experience, an online home for users, a space where virtual life is contained and lived, even after physical death.

It's All About Me

Recognizing the ways in which Facebook reconfigures the permanence of death brings us to my second observation regarding this age of digital mourning: death-related egocentrism. That is, instead of explicitly mourning—or even mentioning—Aaron’s death, Facebook users view his continued virtual existence as an outlet for them to share concerns and needs about their own lives, positing Aaron as an ever-available heavenly intermediary. The posts I have observed express candid requests for help from Aaron, explicitly describing the ways in which he can positively intervene in the lives of the living:

- “please help me finish up my last year of school. give me the strength to get through this so i can finally be a RVT!”

- “hey [aaron]. help me with my princeton app please. only you can. i love you.”

- “thanks for getting me through my surgery well. now please help my dad get through his!”

- “some advice would be appreciated. you always come through for me”

- “Thank you for helping me out with my Mirco exam on thursday means alot....Plz help me out this week for finals!! Miss you”

As evidenced by the above posts, the living Facebook users seem to view Aaron as a heavenly intermediary through an egocentric focus, casting Aaron as an intercessor present and available to meet their needs.

The constant accessibility of digital technologies undoubtedly feeds into this online egocentrism. We spend countless hours uploading pictures, videos, and details about ourselves to multiple social media platforms. Why? Because we can.

More specifically, we can no matter where we are: work, school, the grocery store, the bathroom. The omnipresence of social media, the fact that we can post from anywhere at any time, promotes an attitude of “individualism [and] self-gratification” (Taylor). Every thought, no matter how inconsequential or fleeting, can be and often is digitally documented, uploaded, and shared.

In the context of Aaron’s Facebook page, then, we can consider the ways in which our ability to access Facebook via any number of digital devices invites these egocentric posts. Not only do we have constant access to Aaron’s page, but also we have constant access to a page where the Facebook user is physically unable to participate. The only activity on Aaron’s page, therefore, is what living users post, turning his page into a breeding ground for egocentricity, a space that gradually becomes all about the living users. A quick look at some numbers illustrates this point:

| Months since Aaron's passing | % of posts that are egocentric |

|---|---|

| 2 | 1% |

| 6 | 30% |

| 24 | 77% |

Today, more than five years after his death, an egocentric focus dominates, suggesting that the longer Aaron is physically absent, the more likely living Facebook users are to conceptualize his continued virtual existence from a self-serving perspective.

Death and iCulture

Most teenagers today (at least in mainstream contexts) cannot recall a time without the Internet. Constituting what has been called the “iCulture” generation, teens occupy a narcissistic sphere dominated by “‘ME’-centered profiles [and] the rise of technologies like cell phones that allow individuals to continually wonder, ‘Who’s called Me? Or texted Me?’” (“The Rise of iCulture”). Perhaps it should not be surprising, then, that egocentrism characterizes the majority of the posts on Aaron’s wall. Aaron was, after all, a teenager when he died as were the majority of his friends.

Considering this specific iCulture demographic leads us to intriguing questions ripe for future discussion:

- In an online culture that values its actions based on the number of likes, favorites, and digital thumbs-up, are Aaron’s Facebook friends continually posting to his wall solely because they believe he can read their posts, or do they also want their peers to see their posts?

- Does Facebook offer a valuable and necessary outlet for teenagers who require and seek out their own forms of memorialization and mourning within a community of their peers? Or, alternatively, does the intense and intimate existence of Facebook within this generation invite the emergence of egocentric memorialization behaviors that would not otherwise exist?

- Does Facebook make public the egocentric behaviors and practices that would otherwise be done in the privacy of one’s own head, home, and/or place of worship?

- Just as many of us today cannot imagine relationships without the existence of Facebook and other social media venues, will we also soon be unable to imagine death without such platforms?

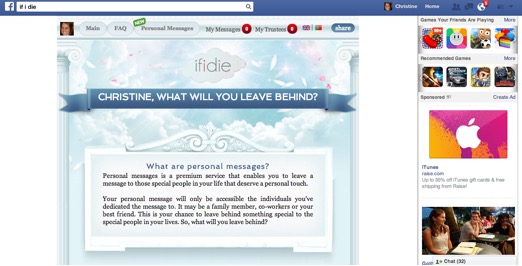

Screen shot from my personal Facebook page after downloading the "If I Die" app.

We are already experiencing what might be considered the next move of “Mourning 2.0” in such things as “Living Headstones” —which have, interestingly, been described as “similar to a personal Facebook page” (Living Headstones)—and funeral webcasting, the live-streaming and digital recording of funeral services.

There’s also the “If I Die” app, an app that tells Facebook users, “You probably don’t remember scheduling an appointment with death anytime soon. And you’re right, but so is death —right. around. the. corner.” The goal of this app is to encourage (or frighten?) Facebook users into recording a post-death video message that will be published after three chosen “trustees” confirm that the Facebook user has, in fact, died.

It seems that the patterns and behaviors I have observed on Aaron’s Facebook page are just one part of a larger shift in the mourning and memorialization practices of this iCulture generation.

Shaping Our Post-Death Identities

The longer Facebook is a central part of our lives, the more pages that will continue to remain active following death and the greater awareness we will have of this future for our own pages and identities. Implicit in this recognition is an acknowledgement of the fragility of our current existence and the understanding that any Facebook profile can, without notice, turn from a "normal" profile to one of a deceased user.

As Aaron’s page reveals, the virtual choices we make today, although perhaps seemingly inconsequential in the present moment, have the potential for indefinite impact. These choices include…

- The profile pictures we post: When Aaron posted his current profile picture, he was unknowingly posting his final profile picture, the one that would greet me each time I access his page, forever positing this image as the face of his post-death virtual identity.

- The messages we type: The messages Aaron posted to his own wall prior to his death, the information he shared in his “About Me” section, and his list of favorite quotes are permanently and publicly displayed on his Facebook page, indefinitely connected to his post-death virtual identity.

- The Facebook friends we accept: Throughout my observation of Aaron’s page, I discovered that only those users who were Facebook friends with Aaron before he died can interact with his page after his death. This means that, in selecting his Facebook friends, Aaron was unknowingly and simultaneously selecting who would help construct his post-death virtual identity.

Ultimately, my hope is that this discussion of Aaron’s page adds to our understanding of online spaces such as Facebook and will lead to more conscious and thoughtful interactions with others, both those who are still physically with us and those who are not.

Christine Martorana is a Ph.D. candidate in Rhetoric and Composition at Florida State University. She is currently finishing her dissertation on feminist agency and activism, a project she loves because it has allowed her to learn from and talk to some very smart, creative, and courageous women. She also enjoys practicing yoga, reading books by Margaret Atwood, and drinking warm lattes.

1. Aaron is not the individual’s actual name. I have changed his name to respect his privacy and that of his friends and family. For the same reason, I purposefully feature Facebook posts throughout this discussion that do not include identifying information about Aaron or other Facebook users. Additionally, based on the visual heuristic of research variables provided in The Ethics of Internet Research (McKee and Porter 88), I decided informed consent was not necessary for this discussion. ↩

2. This phenomenon is occurring so regularly that both Google and Facebook are responding: In April of 2013, Google piloted an “Inactive Account Manager” that offers Facebook users the opportunity to suspend their account after a designated period of inactivity. This feature is “targeted at people who want to create an automated digital will” (Gates). Additionally, Facebook offers the option to memorialize a Facebook user’s page. While the Facebook page remains active after it is memorialized, no new friend requests can be accepted and no one can log into the memorialized account. ↩

3. In September of 2005, Facebook registration opened to all high school students rather than being limited to only Harvard students, as it originally was. Aaron joined Facebook in 2006 as a high school freshman; at the time, more than 25,000 high schools were represented on Facebook (Zeevi), and Facebook quickly became one of the top means of socializing for Aaron’s generation.↩

4. Jeff Bullas reports that a quarter of Facebook users admit to checking Facebook at least five times a day. ↩

5. It is not possible to include every available example here; thus, select examples have been chosen for this discussion. Additionally, I quote the Facebook posts exactly as they appear on Aaron’s Facebook wall; the exact spelling and syntax of every post has been preserved.↩

References

Brondou, Colleen. "Grieving 2.0: As Students Turn to Facebook to Mourn, How Should Parents, Teachers and Counselors React?" Finding Dulcinea. 28 Sept. 2010. Web. 7 Aug. 2014.

Bullas, Jeff. "22 Social Media Facts and Statistics You Should Know." jeffbullas.com n.d. Web. 8 Dec. 2014.

Dobler, Robert. "Ghosts in the Machine: Mourning the MySpace Dead." Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Ed. Trevor Blank. Utah: Utah State University Press, 2009. 175-193. Web.

Farber, Lauren. " American Vernacular Memorial Art: The Politics of Mourning and Remembrance." Major Research Project. (2003) London: The London Institute, Camberwell College of Arts.

Gates, Sara. "Google ‘Inactive Account Manager’: New FeatureHhelps Users Plan for Death." The Huffington Post. 11 April 2013. Web. 10 May 2013.

Living Headstones. Quiring Monuments.2013. Web. 09 Aug. 2014.

Petrecca, Laura. "Mourning Becomes Electric: Tech Changes the Way We Grieve." USA Today. 30 May 2012. Web. 30 July 2014.

Seligson, Hannah. "An Online Generation Redefines Mourning." The New York Times. 21 March 2014. Web. 29 July 2014.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1973. Print.

Taylor, Jim. "Narcissism: On the Rise in America?" The Huffington Post. 28 May 2011. Web. 29 July 2014.

"The Rise of iCulture." The New York Times. 24 Sept. 2007. Web. 29 July 2014.

The World Wide Cemetery. 2014. Web. 08 Aug. 2014.

Zeevi, Daniel. "The Ultimate History of Facebook."Social Media Today. 21 Feb. 2013. Web. 29 Aug. 2013.

Table of Contents image credit: "Drowning in Social Media" by mkhmarketing on flickr