Lives in Movie Stills: Pedagogy, Bruce Lee and Me

Michael Soares

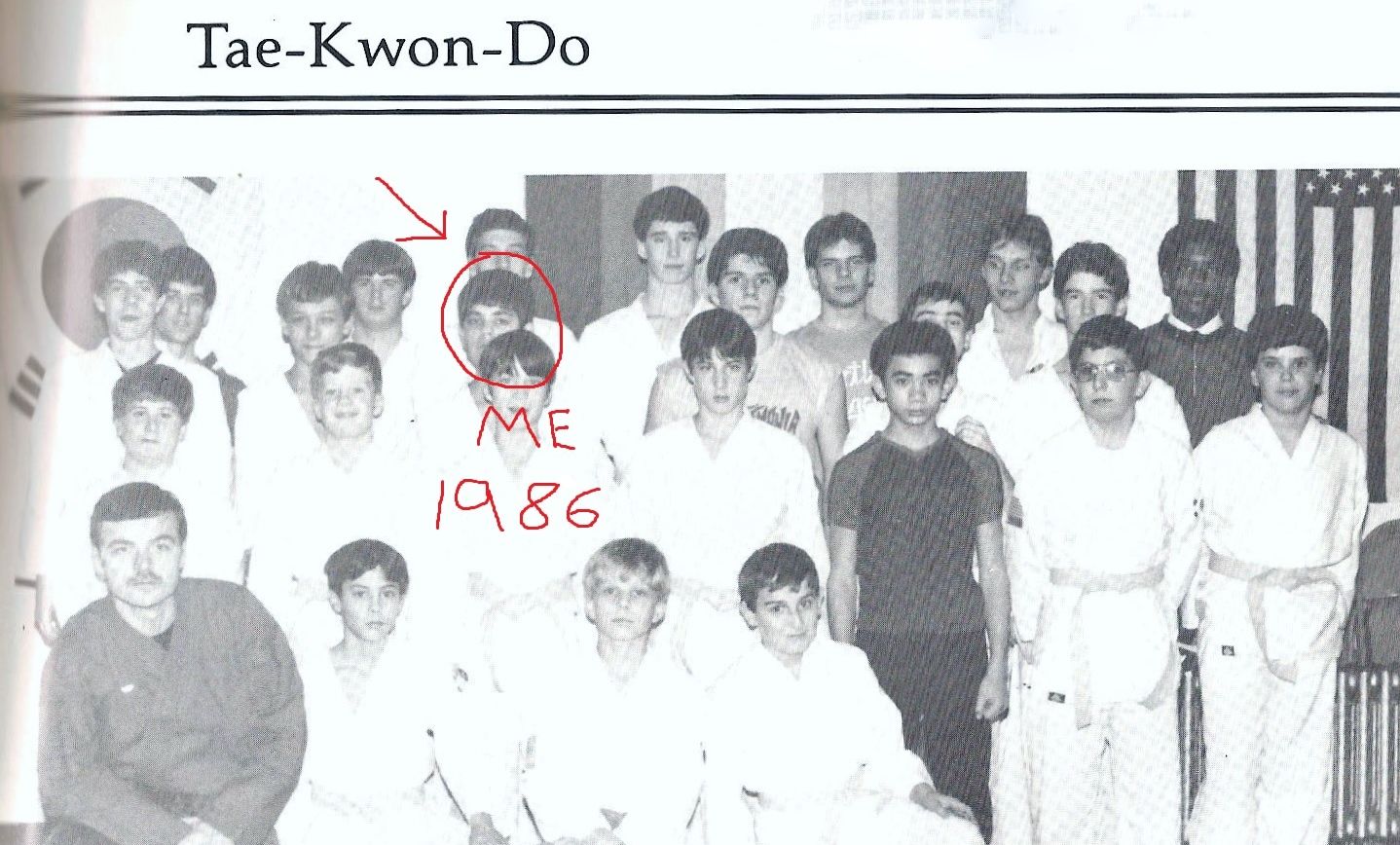

How much influence does the cinema of our youth have on our identities? When I was thirteen, the personae of my friends and I were profoundly shaped by our discovery of Tae Kwon Do. Bolstered by hit "karate" films of the 1980's, in our minds we were ninja warriors and martial arts champions.

Nearly thirty years later, the memories of my Tae Kwon Do experience and the imagery of 1980's martial arts films have created what Meaghan Morris describes as an "inner life." In this essay, I examine a cultural form that challenges the reductive tendencies of political correctness and celebrates its rough edges as a framework for understanding the creative process and its persona-creating properties.

Dragon Up Memories

The author in 1986.

In 1986, I belonged to a Tae Kwon Do club. Sponsored by a Baptist school in eastern Massachusetts, the club met daily, and my friends and I were hooked into the 1980s martial arts craze. We kick-boxed in our school uniforms outside after school, browsed Black Belt magazine to uncover the ancient code of the ninjas and read advertisements for throwing stars and nunchucks, and joined a generation of children who were introduced to the hybridization of Hong Kong and Hollywood movies, developing a long-lasting aesthetic taste for what we then generically referred to as “karate.”

In our minds, and after our Bible lessons (talk about hybridization!), we were ninja warriors and martial arts champions, personas created and bolstered by hit films such as The Karate Kid (1984), The Last Dragon (1985), American Ninja (1985), and absolutely anything starring Chuck Norris. (I remember reading a T-shirt that said, “Jesus could walk on water, but Chuck Norris can swim through land.”)

Nearly thirty years later, the karate memories retained are an articulation not only of my Tae Kwon Do experience but of the peripheral imagery generated by the 1980s karate media, including martial arts films. In “Learning from Bruce Lee: Pedagogy and Political Correctness in Martial Arts Cinema,” renowned cultural studies scholar Meghan Morris looks deeply into a cultural form that challenges the reductive tendencies of political correctness and celebrates its rough edges as a framework for understanding the creative process and its persona-creating properties as narrative for us all. These articulated images, imagined as film stills, create for many of us an “inner life” (Morris, “Learning” 43).

Far from marginalizing this persona-making experience, Morris embraces it and investigates the Hong Kong movie genre for its rich texts and complex implications for cultural studies. Tagging along with Morris’s argument, I offer myself an archive of those inner film stills, tracing their impact on the building of persona during the influential years of my adolescence.

Waxing (On/Off) Sentimental

Without question, film has had a profound effect on our personal developments of persona, and those of us hitting adolescence in the 1980s were somehow particularly ripe for this phenomenon. By the mid-80’s I was in junior high, and the cool factor for lightsaber fights on the lawn had lately waned; the Star Wars toys were fated to meet their demise at the hands of the true scourge of the universe: my younger brothers. Filling the Jedi-sized vacuum was the karate movie in all its culturally hybrid glory.

The films we liked the best were grounded in an 80’s “feel” replete with haircuts and clothes designs of the period, contributing to a genre distinctive enough to be easily detected by my sixteen-year-old son (a savvy resource for what current high school students should not look like) who feels, upon detection of a Reagan-era film on the TV screen, the liberty to complain loudly, “Oh geez, Dad, not again.”

But what my son does not realize is that the sophisticated gentleman before him―drink in hand, spilling crumbs on the couch and telling everyone within earshot that “I used to be able to kick like that”—learned to be me in profound ways because of films like these.

The movies I gravitated towards featured the tough loner or the hardened vigilante. I was never going to be a John Cusack, despite Lloyd Dobler’s desire to be a kickboxer in 1989’s Say Anything. Lloyd was too open, too honest, too vulnerable, and while goodness knows I’ve used Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” to get my girlfriend’s (now my wife’s) attention a dozen times over, I knew at the time I wanted to be that hard-scrabble martial arts master who clung to shadows and emerged only to dispense martial arts justice.

Inner Life of Films

Something insidious got in the way of viewers appropriating the film persona, and it was the film critic. Imposing their will through movie reviews and cinema criticism, the persona-making magic of film was in jeopardy. Morris, bothered by an “armchair way of seeing or not seeing films,” objects to the “hissing moral outrage” from all sides, including at movies like Natural Born Killers and Silence of the Lambs for their puritan-taste offending violence (“Learning” 39).

Conversely, she recognizes critics who abandon discerning critique for a disengaged celebration of aesthetics, resulting in a failure to engage any differences between a children’s movie like The Lion King or a movie about a prostitute called The Good Woman of Bangkok. Morris finds this pattern troubling, but it also motivates her to respond, and she fantasizes about countering the outrage by mass-producing the short film Violence in the Cinema, Part 1, directed by George Miller.

Miller, a former medical doctor (really, look it up!) and the creator of the Mad Max series (films that both rely heavily and comment upon violence), debuted his 1972 short film featuring a droning film critic with an exploding body who continues to drone on through blood and gore. By foregrounding the violence against the backdrop of objectively disengaged film criticism, Miller challenges the “moralistic sampling” of critics and ridicules a politically correct aversion to violence on film seen as anything less than “film-making, make-believe, and aesthetic situation” (“Learning” 40).

“Political correctness” is a term that has evolved over the years, and its meaning is even today the topic of much argument. Jim Stockton of Boise State University highlights “the rather heated debate over the origin of the phrase ‘to be politically correct,’ and, conversely so, ‘to be politically incorrect’” (160). Stockton reports that the term, with origins in “Marxist-Leninist educational maxims in the early 1920’s,” was co-opted by conservative voices to represent something pejorative, rendering a different meaning and distorting its original use. He further suggests that “the adoptive reasoning employed by those critics who view PC as belonging to one particular political camp or another can be applied to any great political thinker, and/or political movement,” making its use as potentially fraught (160-161).

With both the meaning and the application of political correctness dislodged from their initial purpose, the term is used, as Morris points out, as a criticism that causes discourse to be “[p]oliced as we are these days by a code of truth to Experience” (“Learning” 42).

The A(Muse)ing Life of Bruce Lee

Morris points to PC criticism as a troubling trend, noting that “Something has changed... it is the every power of art and imagination—more exactly a politics of gaining access to some freedom and power to make-believe—that is now at stake” (42). Both inspired and irritated by University of Central Florida’s Sam Rohdie’s “Sixth Form Teaching in Hong Kong,” she agrees that while “…aesthetics is fundamental to film teaching,” Rohdie’s approach is dangerously “too fundamentalist” and creates problematic spaces between the viewer and the film—troubling “divides between ‘art’ and ‘society,’ ‘fiction’ and ‘reality,’ which the social critic, a bad spectator, all too flatly denies” (“Learning” 41). Morris is more moved by Leslie Stern of UC San Diego, who writes in her book, The Scorsese Connection, “movies are not imaginary; they constitute part of my (our) daily life” (qtd. in “Learning” 41).

Illustrating this concept is the character of “Jason,” the protagonist of a “banal” and “poorly made, roughly acted” film No Retreat, No Surrender released in 1985 (“Learning” 42-43). Jason exists in a world informed by media—in this case featuring Bruce Lee. Amid the magazines, books, posters and films, Jason has created what Morris describes as an “inner life... made of film stills” (“Learning” 43). In fact, Jason fantasizes about a “Muse” in the spectral form of Bruce Lee who brings the film stills to motion and serves to help shape his path, and create a persona, towards being a hero.

No Retreat, No Surrender (1985)

Morris places the Bruce Lee Muse in context with Rohdie’s argument about the “act of regarding reality” and “the proper use of images in media-shaped reality,” framing the interaction of the two characters as “positive pedagogy” (“Learning” 44). As a “training” film in the same vein as The Karate Kid or Rocky films (and The Empire Strikes Back, arguably), No Retreat, No Surrender “give[s] us lessons in using aesthetics—understood as a practical discipline, ‘the study of the mind and emotions in relation to the sense of beauty’—to overcome personal and social adversity” (“Learning” 45).

Political correctness as a critique challenges these lessons. By commenting on the reality of aesthetics, it ignores this concept of “inner life of films” that the viewer is transferring into his or her reading of the film. But I’ve still got a Yoda on my back—or rather, I’ve got internalized film stills of characters and filmscapes, and like Jason’s Muse, they have informed my personae-building. PC threatens to sabotage those stills unless I strike back.

Without question, in a media-saturated culture, we all bring deep-seated perceptions of reality, often informed by our life-long exposure to film, to the reading of a text. In “Psychodynamics of Political Correctness,” Howard S. Schwartz of Oakland University discusses PC as the representation of “psychological regression” and further states “it is important to reiterate that regression is not necessarily bad.” In fact, he cites other psychoanalytic thinkers who have observed that “regression is a necessary element of creativity” (Schwartz 145). When Jason taps into his regressive inner life, Bruce Lee Muse is manifested.

Yoda as desktop companion.

Ultimately, a reading through the critical lens of PC inhibits the “media pedagogy” experienced by Jason and, vicariously, those of us studying the film. It also inhibits the conception of persona. I liken the dilemma to that of my own. While I, former Tae Kwon Do blue belt, may not be able to fit into my karate uniform anymore, I do need to fit my inner life, regressed or otherwise, into the reading of No Retreat, No Surrender’s aesthetics without the interference from the “new” political correctness.

No Offense, Mr. Miyagi

Next, Morris speculates that “martial arts films today compose a fuzzy place between the critically visible grandeurs of ‘Hollywood’ and ‘Hong Kong’” (“Learning” 45). This hybridization allows “a hard-edged allegory of the text as a reflection of its own creative process, No Retreat, No Surrender could plausibly be seen as a Hong Kong film that cleverly accessed a US market by retelling the classic ultimate story (“Outsider makes good”), using Bruce Lee, the ultimate migrant crossover star” (“Learning” 47). The film uses two powerful techniques to showcase “the power in reality which images can have”: pragmatic variation (“never can succeed without a surprise”) and productive repetition (“practice makes perfect”) (“Learning” 48).

Pragmatic variation, or “never can succeed without a surprise,” is shown through the Muse’s grip-breaking martial arts demonstration. This is not unlike in another more contemporary film using martial arts training, Batman Begins, when Ras Al Guhl tells a young Bruce Wayne that his parents’ death was his father’s fault, breaking his concentration and making him vulnerable to a leg sweep demonstration. Likewise, Jason is able to show how productive repetition is necessary to the training film genre when he catches an apple without thinking after many similar repetitions on an exercise machine.

The test is reminiscent of the iconic scene in Karate Kid (1984) when the Ralph Macchio character learns that “wax on, wax off” was indeed training for a defensive martial arts technique. Indeed, it is often in this very “test” situation that the characters in question make those persona-forming breakthroughs which propel them into the glory the viewer has come to witness.

Morris’s No Retreat, No Surrender discussion ends with the observation, “In most martial arts films, banality is a source of power; as practice, repetition, training, the ‘dull gestures of everyday reality’ intimately form the martial artist and bring wonder into the world” (“Learning” 49).

Despite that, training sequences are often presented in condensed montage form, perhaps shielding the viewers from the full impact of the sequence’s implied banality, I would argue that the sheer repetition of watching particular films and others like it distilled a certain magic personae-building potion that we eagerly ingested.

Likewise, the forces which would prevent the audience’s intimacy with the text by restricting that which shapes us must be carefully considered. In “Banality in Cultural Studies,” Morris writes

“If I find myself in the contradictory position of wanting to reject the patronizing idea that ‘banality’ is a useful framing concept to discuss mass media, and yet go on to complain myself of ‘banality’ in cultural studies, the problem may arise because the critical vocabulary available to people wanting to theorize the discriminations that they make in relation to their own experience of popular culture—without debating the ‘validity’ of that experience, even less that culture as a whole—is still, today, extraordinarily depleted.”

Enter the Biopic

Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993)

This depletion is in play as Morris considers Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993), a creatively biographical film featuring implicit commentary on the tensions of American and Hong Kong culture played out through the media of Lee’s life. She describes a scene in which Lee is with his future wife, Linda, at a movie theater as they watch Mickey Rooney’s raucous and racist rendition of a Japanese man in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. While she and the audience are laughing, she turns to see a profoundly disturbed Lee frowning. She immediately discerns why he is upset and acts accordingly; she invites him to leave the show with her, and they move outside the theater to embrace.

The audience, also, is “cued” as to how one should feel in this situation, and it is in this transaction that Morris questions “validity” when it is skewed by an invasive “political correctness” reading. Morris contends that, “PC is not primarily a code regulating expression but a spectator’s revolt” (“Learning” 51).

Her argument is that political correctness reading can occlude the viewer in ways that that detract from the reading of the text, convinced that “cinematic negotiation involves you, the films, and other people” (“Learning” 52), and suggesting that the narrowing aspects of political correctness constrain a fuller realization of the film’s impact. For example, Morris writes, “What makes Dragon so rich a commentary on cinema is rather that it frames its ‘critique’ of Breakfast at Tiffany’s as an episode in a broader narrative about Bruce Lee’s dream of making martial arts films himself” (“Learning” 54).

By manipulating the audience to see the Bruce Lee scene as one of primarily racism, it misses the potential of an “inner life of film stills” the viewer can access to make his or her own reading. Morris concludes that, “My argument is not about whether a film or a genre ‘is’ whatever we mean by PC. I’m suggesting on the contrary that ‘PC’ is a term that can’t settle in a stable content, a smooth spectrum of complaints, a single ‘orthodoxy’ or dogma” (“Learning” 56). She even describes how, while showing the film in Australia, debates have formed concerning if and why Bruce Lee would have even identified with a Japanese man on film, casting doubt on the veracity of the scene, never mind the emotions the scene intends to elicit.

My point here is not to cast shadows on the public discourse of film; in fact, my concern is much more personal: to resist any PC proclivity towards unduly overexposing my inner film life. I control the critique. My thirteen year-old self, junior high Tae Kwon Do wanna-be, whose inner life which was in part created by film stills from Bruce Lee movies, remains safely mediated by my present self with our own autonomous discourse, for better or worse.

And while those memories may have partially regressed, those persona making touchstones can still rapidly emerge as Jason fights Ivan the Russian, or Rocky fights Drago the Russian, or a not-quite Jedi Luke Skywalker engages a dangerous Sith Lord for the first time. Bam! Crash! Pow! Oh yeah.

Beyond the Blue Belt

As an adult, I have found that the tension between persona making and political correctness is a story that lost traction past those teenage formative years. As time grew on, the Tae Kwon Do uniform disappeared into the parents’ attic, not before my mother washed it in the same load as my maroon corduroys and briefly turned it pink (not exactly the persona forming strategy I had in mind at the time). Eventually the Black Belt magazines suffered neglect, probably “borrowed” by my younger brothers who were in the process of their own martial arts-inflected persona making journeys (though likely more influenced by the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles than Bruce Lee).

Ultimately, the persona changed to meet the needs of career and children, and the Tae Kwon Do was irrevocably replaced with Too Much To Do, with the immediacy of life necessities overshadowing any concerns political correctness might have otherwise imposed.

However, once in a long while, when I head down into the cellar to crack open the dusty bin which contains the relics of my childhood to retrieve my birth certificate or just to breath in the faint remaining wisps of a young me, the internalized childhood persona stirs to make a mental round house kick, and I know that somewhere inside me is the ninja, pushing me through a PhD, into two decades of teaching, into being the best father of three I can possibly be. And to hell with political correctness.

On a final note, the latest version of “Learning from Bruce Lee: Pedagogy and Political Correctness in Martial Arts Cinema” was published in 2007, with other versions of the essay published years earlier; therefore, it is unclear when Morris writes, “Whether the term itself will have currency for much longer, I have no idea” (56) to when she is actually referencing. With no possible reason to expect that she would reply, an e-mail was sent inquiring as to her thoughts on the current power of the idea of political correctness.

Fortunately, Professor Morris was more than happy to respond, and in short she replied, “It’s hard to generalize, but although the term is still used angrily to apply now to just about *anything* vaguely branded ‘progressive’ in the right-wing/Murdoch press, still trying to stir up culture wars, I think the use of it in Australia has subsided to something subcultural again—people of a certain age might use it in universities or in government bureaucracy contexts, but mainly to joke or to distance themselves from some reaction perceived as extreme or literal-minded.”

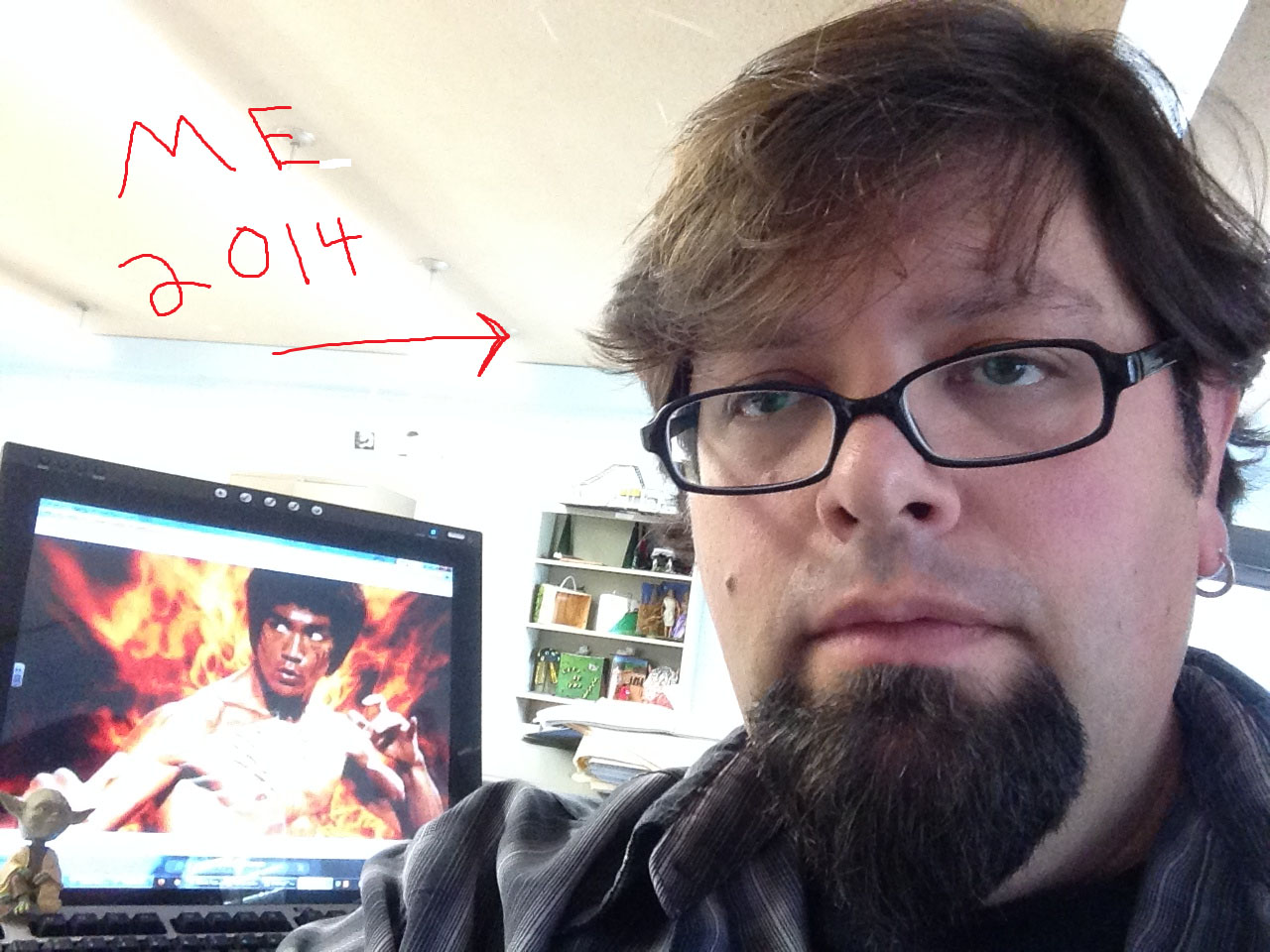

The author in 2014.

Similarly, in the United States, political correctness seems to also have lost much of its impact—at this point appropriated by conservative voices characterizing the folly of dissenting viewpoints. In the academy, the concept is also fairly passé, an opinion reinforced by Jeff Rients, Illinois State University PhD student and esteemed colleague, who when asked if political correctness still had currency in 2013, succinctly and amusing pointed out, “Man, I don’t know if I give a shit.” Jeff cracks me up.

In fact, just below my forty-one year old exterior a fourteen year old me is even slightly in awe of Jeff’s brazen words, spoken with the force of his own inner ninja. Resolved to be undeterred by forces of political correctness, I can continue experiencing and critiquing the films I appreciate and love through the lens of my own inner film stills, secure in my personas past and present, and maybe even busting out an old Tae Kwon Do move when I think nobody is watching…

References

Morris, Meaghan. "Banality in Cultural Studies." Block #14. www.Hausitte.net. 1991. 11 Nov. 2013. Web. http://www.haussite.net/haus.0/SCRIPT/txt1999/11/Morrise.HTML

----. "Learning from Bruce Lee: Pedagogy and Political Correctness in Martial Arts Cinema." The Worlding Project: Doing Cultural Studies in the Era of Globalization. Eds. Ron Wilson and Christopher Leigh Connery. Berkley: North Atlantic, 2007. 38-59. Print.

---. "Re: Grad Student Question." Message to Author. 7 Nov. 2013. E-mail.

“Professor Meaghan Morris.” Academic Staff. The University of Sydney. N.p. Web. 7 Nov. 2013. http://sydney.edu.au/arts/gender_cultural_studies/staff/profiles/meaghan.morris.php

Rients, Jeff. “Discussion Worksheet.” Handout to ENG 560. Illinois State University. Normal, IL. 11 Nov. 2013. Print.

Schwartz, Howard S. "Psychodynamics of Political Correctness." Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 2 (1997): 133-149. Academic OneFile. Web. 14 Nov. 2013. http://www.sba.oakland.edu/faculty/schwartz/PCJABS.htm

Stockton, Jim. "The History of Political Correctness." International Journal of the Humanities 5.12 (2008): 159-162. Humanities International Complete. Web. 14 Nov. 2013.

This article includes links to video clips from the films No Retreat, No Surrender and Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, which are copyrighted material. The inclusion of such material in this article for critical, scholarly, non-commercial purposes constitutes Faire Use, as provided for in Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law.