Ignoring Ethics with Style: Writing Sentences for "Non U.S. Persons"

Ryan Smith Madan

Many of us remember the aftermath of Edward Snowden's leak of classified information for its implications for national security and citizen privacy. But the national conversation following those events also reveals important questions about language and writing—especially about bureaucratic obscurity promulgated by confusing prose. By focusing on an exchange between Director of Intelligence James Clapper and Senators Ron Wyden and Mark Udall, I explore how the issue of clarity in writing can be a matter of ethics, as sentences conceal and reveal to the benefit of some and the detriment of others.

Read this sentence and tell me what it means:

Based on some of these terms—declassified, foreign intelligence, FISA—you can probably guess what the sentence is about. It was written by the Director of National Intelligence, James R. Clapper, in a letter to Congress (dated March 28, 2014) clarifying the legality of the government surveillance practices unearthed by Edward Snowden's 2013 leak of classified material.

But beyond your general sense of the topic, can you decipher what Director Clapper’s sentence is really saying? Try reading the sentence again, slower this time: "As reflected in the August 2013 Semiannual Assessment […] there have been queries, using U.S. person identifiers, of communications […] by targeting non U.S. persons." Even on second look it's a real challenge.

This government-scandal-of-our-generation is not, I think, intuitively filed under the category of "writing problems." After all, the real story here is the widespread surveillance of U.S. citizens and our eroding privacy in the face of increasing national security pressures. But nonetheless I think it's worth pausing to discuss what's happening in sentences like these.

My goal is not just to make a point about "clarity" (I don't think you need convincing that the above sentence is unclear to most readers); nor are you probably surprised that such a sentence could originate from an intelligence-agency author. Rather I want to reflect on that moment, often taken for granted, when a matter of clarity becomes a matter of ethics.

While Clapper's letter teaches us precious little about the substance of government information gathering, it does reveal quite a lot about a certain rhetorical approach born out of a certain kind of sentence writing. It's a rhetorical approach we ought to attend to more closely if we hope to pose resistance to the small- and large-scale intrusions that we'll likely face again as our national political figures sound ever ready to sacrifice civil rights at the altar of national crisis.

The Structure of Clarity

To begin, let's root ourselves in the mechanics of Clapper's sentence. What characteristics cause that feeling of density? We could point to a cluttered introductory passage (28 words before we get to the main clause), or we could note the series of halting asides (those comma-enclosed parenthetical ideas) that strain the reader's attention.

But there's something else to notice, too—a writing problem discussed most usefully by Joseph Williams, the late author of Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace (updated in later additions by the late Gregory Colomb and now Joseph Bizup). Williams et al. claim that we appreciate, because we easily comprehend, sentences that "[tell] stories about characters and their actions" (29). "The two most general principles for clear sentences are these," the text says: "make main characters the subjects of your verbs; make those characters' important actions your verbs" (44). And if the characters are "flesh and blood" and the actions vibrant and visual, the sentence will be all the clearer (52).

Easier said than done. As Style shows, writers too often bury the most important characters and actions in the chaff of their sentences or leave them out altogether. The result: sentences suffer, and so suffer reader engagement and understanding.

Let's consider potential characters in a government wire-tapping scandal. Who might such a story be about?

Al-Qaeda, ISIS, or other terrorist groups

American citizens

President Obama

The White House

Congress (and its leaders)

The CIA, NSA, & Department of Homeland Security (and their directors)

Even the short-list promises quite a drama, doesn't it?—a Beltway controversy with high stakes and a compelling cast. (Oliver Stone knows it; he's cast Joseph Gordon-Levitt in his upcoming biopic.)

But which characters actually populate Clapper's sentence? Which protagonists wait in the wings, ready to take stage as the sentence's subject?

Semiannual assessment

Section 702 of FISA

We

Queries

Non U.S. persons

U.S. person identifiers

Communications

Foreign intelligence

Putting aside the "we" (which itself refers to no concrete antecedent in Clapper's letter), this is a list of the most flaccid heroes. Nor can the sentence's verbs do much to animate these characters. Query, identify, acquire, target, locate: all have great potential. But the sentence disguises them as nouns and modifiers, leaving "have been"—the true verb of the main clause—with the impossible burden of propelling the reader forward. There have been queries. Queries have happened. This is what Director Clapper has taken time out of his day to tell Congress.

Action verbs would help, but even so, Clapper's cast of characters is all wrong. What wizard could conjure a vivid story using these "actors"?

U.S. person identifiers enable the acquisition of foreign intelligence.

Section 702 of FISA authorizes queries of non U.S. persons.

Communications of non U.S. persons were reviewed in a semiannual assessment.

The "non U.S. persons" in these sentences are also non-characters, ghosts of redacted ideas. Their stories are ghost stories—but not the kind anyone would want to hear, not even conspiracy theorists swooning over all this leaked material. "One dark and stormy night, a U.S. Person Identifier was queried in order to—" "Nope. Off to bed. See you in the morning."

Instead, our brains reach for story.

If a U.S. citizen contacts a foreigner, CIA analysts can read those communications without a warrant.

Congress may revoke NSA powers to surveil digital communications.

President Obama denies the illegality of collecting bulk cell-phone data.

Senator Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the lucky addressee of Director Clapper's letter, responded with some much needed clarity. As I read it, Wyde's public statement, co-authored with then-Senator Mark Udall (D-Colo.),1 corrects Clapper's language as much as it reprimands the policies obscured by that language. "This is unacceptable," the senators say about the "warrantless searches of the content of Americans' personal communications."

It raises serious constitutional questions, and poses a real threat to the privacy rights of law-abiding Americans. If a government agency thinks that a particular American is engaged in terrorism or espionage, the Fourth Amendment requires that the government secure a warrant or emergency authorization before monitoring his or her communications. This fact should be beyond dispute.

Literary stylists probably wouldn't laud these sentences as especially crisp and bounding, but in contrast to the text they rebuke the prose is practically amphetamine. Why the feeling of lightness and energy? Why the sense that these are words written by humans for other humans? Look at the one-two punch of concrete characters and actions, many of them mapped onto the clauses' subjects and verbs.

Now, to be clear, Wyden and Udall don't sell the farm when it comes to transparency. The senators, too, depersonalize their language to maintain political decorum, shaming intelligence-gathering policies over and above intelligence officials: "However, the facts show that those suggestions were misleading..." claim the senators. As facts wrestle with suggestions in D.C.’s back alleys, the senators and the director can, one supposes, have less awkward small talk next time they bump into each other at the White House cafeteria.

But even with the hedge, the effort is there—at least in structure—to tell it straight, to educate citizens who might want to know. In so doing, Wyden and Udall's response promises a different worldview made possible by a different relationship to language.

The Politics of Clarity and the Ethics of the Impersonal

It is tempting to laud the senators' achievement as, quite simply, a triumph of sentence-level clarity. We can look at these two passages, the senators' and the director's, side-by-side and say that one is accessible and the other is not; one allows understanding (and therefore action) and the other does not.

But the discord between the director's letter and the senators' response reveals something else, too, about what it means to write "clearly." Clarity is not a thing-in-itself; it does not reside in a sentence (though Williams et al. show how certain sentence structures are more friendly to clarity than others). Rather clarity emerges only in an ephemeral moment of transaction as information passes between writer and reader.

Depending on a writer's decisions and the readers' location, the "story" told by a sentence can be more or less resonant or more or less inscrutable. Ideas plated up in the kitchen are consumed in the dining room, and what gets served and how it's prepared affect not just the flavor of the meal but also its digestion—the way the meal is metabolized, the way it sits in the gut.

More than the matter of simple clarity, it's this power of the sentence that draws me to the exchange between Clapper and Congress, the power of the sentence to invite reader understanding—or to disrupt it. Clapper’s letter paints a truth, but whose? It invites a conversation, but whom does it exclude?

Such questions force us beyond a too-easy discussion about whether a text reads clearly, to think instead about what is offered and what is withheld. As such, this question of writing mechanics (where a sentence's information is located and in what form) becomes inseparable from a question of sentence ethics (what information is presented and to whose advantage).

All bureaucratic writing (not just Clapper's) tends to obscure more than enlighten. But, as readers, we too often accept that obstruction, chalking up confusion to our own ignorance or to the text’s unfortunate—but inevitable—professional provinciality. As though a bureaucratic document, having spent its adolescence living in a wolf den, couldn’t therefore be expected to converse with regular townsfolk. We shrug off the linguistic quirks, the inhuman tone, the presumptions and impositions; we suppose, perhaps, that in the world where an Intelligence Director lives "U.S. person identifiers" are the kinds of characters one tells stories about.

I don't disagree with the point. But even so we should not be too generous about the position such writing puts us in. Clapper's narrative, appropriate as it might be to an audience of intelligence brokers, leaves the rest of us in the lurch. The "characters" in his sentence are not the people we work with; they are not our neighbors or friends or families; they are not ourselves.

By placing this intelligence story in some parallel universe of 'non-persons," Clapper shuts down, rather than solicits, public participation about a matter that is fundamentally about us: surveillance done to us in the name of our security. Sadly, Clapper's story is no better suited for his audience in Congress, where it fails to remind the People's Representatives that flesh-and-blood citizens lurk behind those "person identifiers."

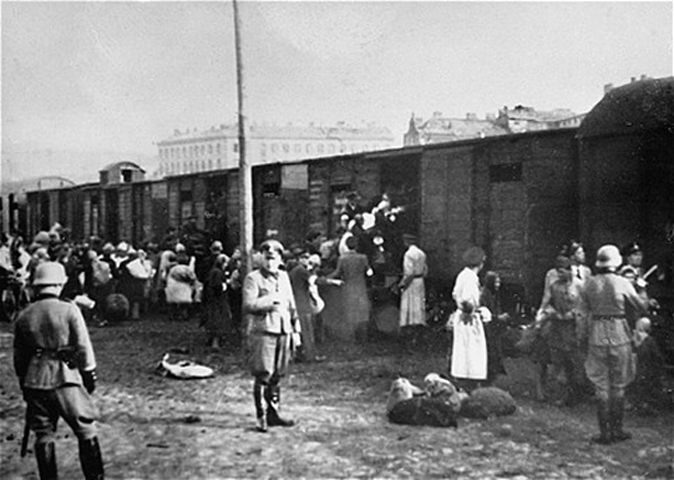

While the bureaucratic origin of Clapper's text might help us understand why it sounds so alien, the erasure of the human from the centrality of the text means the damage has already been done. George Saunders has written brilliantly about the disturbing consequences of the impersonal. "[A]ll attempts at world domination begin with weak, evasive, impersonal language," Saunders writes in "The Battle for Precision." A bit of hyperbole, we assume, until Saunders illustrates the point. He excerpts a 1942 memo (translated) from an S.S. officer to his boss, addressing a troublesome "managerial" problem:

It has been observed that when the doors are shut, the load always presses hard against them as soon as darkness sets in. [...] This is because the load naturally rushes toward the light when darkness sets in, which makes closing the door difficult. Also, because of the alarming nature of darkness, screaming always occurs when the doors are closed. It would therefore be useful to light the lamp before and during the first moments of the operation.

Saunders provides little detail about the quotation’s source or specific context. But the little information we get is enough to fascinate and horrify in equal measure. While the memo enacts the hallmarks of bureaucratic circularity—the euphemisms, the jargon, the de-personalized syntax—these are not meant by the letter writer to obstruct the truth from an on-looking public (this is an internal document, we are told, from subordinate to supervisor).

Warsaw, Poland: Jews being loaded onto train cars

for transportation to Treblinka extermination camp

Rather the writer's worldview forms the very bones on which the sentence-flesh hangs: in the eyes of the bureaucrats of genocide, the main characters of this story—Jewish lives—are indeed just a "load," a shifting mass slowing the progress of efficient transport, a cargo that occasionally, and disruptively, screams. The language both mirrors and reaffirms its discourse community, a place defined by certain kinds of problems (of an administrative kind, not a people kind) and a certain set of available approaches to solve them— Unearth the blueprints, the flow charts, the strategic plans. The Operation needs a fresh approach.

Saunders gets our attention with the horrendous weight of the example. But the rest of his essay is, surprisingly, equally powerful as he calls out the rest of us (the non-despots) for depersonalizing language to the point of untruth. We all lapse into "lazy dishonesty," he says—not from malicious intent but from a natural complacency, a failure to will-into-being language with enough edge to scratch down to the truth. (Saunders, a winner of a MacAurthur Genius Grant for his writing, admits he's not exempt from this impulse). To write "lazy" sentences, Saunders implies, is to opt out of an ethical obligation to represent the world as nakedly as possible, an obligation that can't (at least not responsibly) be escaped.

Writing (and Reading) Ourselves Back Into the Story

I worry that we aren't a public that's terribly attentive to, or knowledgeable about, the ways certain sentence-forms enable such withholdings. It's not that we ignore the importance of writing; rather we worry over the wrong things. I'm reminded of this almost every time a new acquaintance discovers I teach writing. The conversation often turns confessional: I still can't name the parts of speech, they blush, or I've always been terrible at commas.

But rarely do I hear apologies for communication's greater sin: failing to deliver meaningful, readable prose to an audience-in-need. What about that time your written instructions proved more confusing than helpful? I want to ask. What about the apology email you sent that actually created more animosity than before?

These are the moments I want to worry over. But the faux rules that dominate so many of our imaginations about writing, paired with an educational and cultural obsession with finding error (as though reading a text were playing Battleship against its author) presuppose a different understanding about what sentences are for and how to go about creating them.

A different kind of writing instruction could help students better attune to the ways sentences, through omission or force, stake claim on this ethical landscape. A different kind of writing instruction, in other words, could help develop not just better writers, but also more critical readers. But as a college writing professor I'm also witness to education's failure to raise these concerns.

Each semester I ask my students to inventory their writing knowledge (after all, by now they've internalized years of school lectures and teacher feedback). Their broad-brush commitments are always heartening: writing should move people, be passionate, animating, meaningful, sincere. But the discrete practices that have been drilled into their memories, the ones they cling to as a means to achieve those lofty goals in their own writing, are overwhelmingly unimaginative: Do not end sentences with prepositions; do not begin sentences with "and" or "but"; never use "I"; use three to five sentences per paragraph (unless your teacher says four to six); never use contractions.

These are lenses of understanding writing through which too many of us still look, and they are lenses that have neither the urgency nor the explanatory power to help us grapple with the ethics of a sentence's story.

If we rely on these lenses to explain the deficiencies in Clapper's letter to Congress, we'd be able to say that the director violates a host of stylistic and usage "rules." But this would be a short-sighted win, for it would suggest that Clapper's writing is his problem. Unfortunately, as with so much bureaucratic writing, his problem is actually all of ours. Clapper uses passive structures and non-person characters to pull forward certain ideas and shroud others, to blur and to name as it suits his intelligence project (There have been queries, using U.S. person identifiers, of communications...).

Image credit: Elliot Moore, Wikimedia Commons

The director's sentence clears a space for him—and his worldview—to stand. His choice of "characters," his omission of a flesh-and-blood public, places us at the bottom of a hierarchy of knowledge as his sentence hoists him into a crow's nest to look down on the sea of the public below. We: the watched, the managed, the overseen. We: the spied upon—not the ones authorized to do the listening. These are the roles scripted for us as readers and as citizens.

Clapper's prose is not special in this regard: all of our sentences do this clearing away, this orienting (whether strategically or accidentally). But the exchange between Clapper and the senators should remind us how much our very participation as citizens—as voters, as clients, as consumers, as thinkers—depends on writing ourselves, or being written, into the stories told about us. Let's take notice the next time someone's sentence leaves us out of a story, or gives us a part we aren't willing to play.

References

Clapper, James R. Letter to Ron Wyden. 28 Mar. 2014. New

York Times. Web. 12 Sept. 2015.

Saunders, George. “The Battle for Precision.” The

Guardian 19 Mar. 2005. Web. 12 Sept. 2015.

Williams, Joseph M., and Joseph Bizup. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace. 11th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 2014.

Wyden, Ron, and Mark Udall. “Wyden,

Udall on Revelations that Intelligence Agencies Have Exploited

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act 'Loophole.'” Press Release. 1 April 2014.

Web. 12 Sept. 2015.