Comic Fans and Convergence Culture:

Community of Readers in The Master of Kung Fu

David Beard and Kate Vo Thi-Beard

As a member of several fan cultures, I have an interest in the processes that fan audiences use to construct and reconstruct the texts they consume. Additionally, I think of the way (written, oral, and musical) texts construct the individuals who constitute their audiences. Examining Master of Kung Fu provided the perfect combination of these two interests.

—David

My fascination with representations of Asians in the media began with The Destroyer book series that I read as a teen. While the character Remo at first resisted his fate, he quickly embraced his identity as

the next Master of Sinanju. As a Vietnamese American growing up in a small Midwestern town, I have slowly come to my identity as an Asian American. I owe a lot of that to my current life as a Ph.D. student. My research has centered around cultural identity and representations in comics, children's literature, and Asian American magazines. These have fueled my desire to learn more about my own identity.

—Kate

It seems that every day, a new article appears about the "arrival" of comics in contemporary culture. It follows, usually, some event that makes people (in business or Hollywood) stand up and take notice. Whether it was Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, Spider-Man's box office records, or Heath Ledger's performance as the Joker, it becomes common to claim that comics can, at last, take their place among the traditionally accepted media.

And when comic books take their place among the accepted media, the dream follows: comics fans can take their place in popular culture. Instead of serving as the punch line in television comedies (CBS' Big Bang Theory; Fox's The Simpsons) or movies (The 40-Year-Old Virgin), maybe, just maybe, comic book fans can be just like everyone else. As someone who, beginning ten years ago, fought the hard fight to teach comic books in the university classroom, David knows the desire for acceptance and the hope for the warm embrace of popular and academic culture.

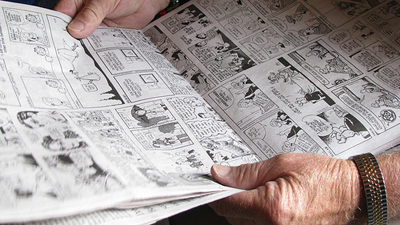

Comics weren't always a niche market and a fragmentary industry, however. At one point in time, a comic book was as ubiquitous a piece of Americana as a can of Coke, and a comic was available for sale in as many places. Comics fans, in those days, weren't necessarily like comics fans today.

It is the goal of this essay to reconstruct the comic fan of yesterday. What follows is not an exercise in fannishness (entirely, at least), but an exercise in reconstructing the communities of readers around a popular text. The study of the reader in this historical case (from thirty years ago) can tell us something interesting about the complexities of being a member of a community of readers today. As fan websites for comics (and tv, and teen fiction) proliferate, we aren't yet thinking through what it means to be a fan in an era of contemporary convergence culture. We're leaping into flamewars over the best artists and arguing over the quality of film adaptations and the declining quality of NBC's Heroes, without time to reflect on the broader implications of what we are up to.

To make our argument about communities of readers in contemporary culture, we survey the study of readers as a field of inquiry, we assess Master of Kung Fu (MoKF) comic books as an ideal object of inquiry, and we analyze the community of readers visible in that comic. The community of fans of MoKF was both [a] a real and genuine community, based on models from social psychology, and at once [b] a community created to advance the goals of the corporation (Marvel Comics). As such, a closer look at this historical community offers some insight for today's comics fandom as they "arrive" in popular culture—and perhaps for the broader communities of fans of other media texts.

About the Study of Readers

"Readers leave few enduring traces of their activities, and researchers interested in what, why, and how people read have to exercise considerable ingenuity in their search for primary data" (Pawley, Reading on the Middle Border, 380).

Traces of individuals' reading habits and practices are difficult to locate. Outside a small number who keep reading journals, there are few readers who leave textual traces of their reading habits. Most reading is done silently and without evidence. Even though some movie-goers sometimes keep the ticket stubs as evidence of movie-going, there are few similar paper trails for readers.

As a result, we look at small bits of evidence from a select few readers and hope for generalizability. We have come to "depend on readers' own writings—published and unpublished letters (including fan mail), essays, commonplace books, diaries, autograph books, journals, autobiographies, memoirs and reminiscences, and marginal annotations—to link real people to the texts that they read" (Pawley, Reading on the Middle Border, 380-381). This essay adds to Pawley's lists of texts that we can use to track down the historical reader by looking to published fan letters in MoKF.

A letter column in a comic book is compiled by one of the comic's staff members, often the book's editor or assistant. Fan letter writers wrote with a purpose, believing that they could influence the direction of the comic, the fate of the characters, and the work of the creators.

Comic book artist Trina Robbins is perhaps the only scholar to have conducted serious research on comic book letters pages. Robbins writes that "One way to judge the readership of a comic is to check the letters page" ("Gender Differences in Comics"). She uses this tool to investigate the readership of comics like Wonder Woman.

Much information can be gleaned from the letters pages of a comic. …. The April, 1962 issue contained letters from two girls and one boy, the May, 1963 issue had letters from five girls, and the October, 1964 letters page was another all-girl affair, with letters from five girls. Judging from their letters, the writers were all young, and they wrote to Wonder Woman herself. ("Wonder Woman: Lesbian or Dyke? Paradise Island as a Woman's Community")Robbins has made analysis of letter columns a part of her research into the history of comics. We learn much from her work, while also advancing beyond her initial research, in our own study of MoKF. For more on method, click here.

About the Object of Study: Master of Kung Fu

We want to justify the study of Master of Kung Fu based on its intellectual merits, its connections to popular culture, and its aesthetic qualities. But let's face it: it's a clever concept, manifest in a serial melodrama that had David clamoring to walk to the newsstand every month. David's mother never understood his fascination with comics—the sixty-cent pleasures that filled his childhood with meaning. She never got that the attraction was twofold: David wanted to know what happened to his favorite characters every month, but more importantly, David wanted to be someone who knew: someone who spoke the special language of comics.

Under examination here is the mass media text that spawned a community of fans across decades of publication: Master of Kung Fu (MoKF), published by Marvel Comics. The comic had an international following. Even today, the comic retains some ardent fans, including Ang Lee, who has proposed to produce a film based on the character.

MoKF was born of the martial arts craze of the 1970s—a cross-media phenomenon. Bruce Lee movies, men's adventure fiction like the Destroyer series (with its invented martial art Sinanju), the highly successful Kung Fu tv show, and martial arts magazines aplenty made clear that "Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting." Multiple comic publishers responded to this craze, releasing titles like Yang, House of Yang (Charlton), Richard Dragon (DC Comics), and, at Marvel, Power Man and Iron Fist and The Hands of Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu.

Master of Kung Fu took its backstory from Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu. Lead character Shang-Chi was introduced as the son of Fu Manchu. Shang-Chi was raised to be the ultimate assassin. However, his first mission ended with Shang-Chi learning of Fu Manchu's true, evil nature. Disillusioned, Shang-Chi swore to oppose his father, with a colorful cast of supporting characters, including British intelligence agents.

The book continued for ten years and 125 issues, developing a rich cast of characters as well as a devoted fan community. It outlasted its peers in the martial arts craze in comics, without ever fully becoming a men-in-tights superhero adventure. In part, this may be because of the unique way that editors and fans met on the letters page of nearly every issue. There, they constituted a community of readers.

The Readers of MoKF and the Features of Community

As a kid, in the waning years of mass market availability of comic books, David felt what most scholars know: reading and writing are typically solitary acts. To envision a community of readers and writers, we must carefully delineate what community means. The community of readers represented in and constituted by the letter columns in MoKF share in the four basic tenets of community in social psychology research. David W. McMillan and David M. Chavis define the sense of community in this way:

Sense of community is a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members' needs will be met through their commitment to be together (McMillan, "Sense of Community: An Attempt at Definition.", 9; see also McMillan and Chavis, "Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory" or click here).We can divide this definition into four broad categories and demonstrate the unique characteristics of this community of readers.

The Readers Share Common Tastes: The Shared Emotional Connection of Readers of MoKF

One way we know that the readers of MoKF constitute a unique community is through the discussion of their common experiences and tastes in comics, in literature, in music. Shared sets of tastes foster a shared emotional connection across readers. According to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, "[Taste] functions as a sort of social orientation, a 'sense of one's place', guiding the occupants of a given…social space towards the social positions adjusted to their properties, and towards the practices or goods which befit the occupants of that position" (Bourdieu, Distinction, 468). In short, taste gives us a social orientation toward some experiences and away others, en route to establishing our own social connections.

Sharing a taste for comics, film, and media yields a common set of experiences which function in much the way that McMillan argues that a shared history can function for sense of community. A shared taste gives us a sense of identity and a sense of place within a community—a sense of emotional connection (click here for more on emotional connection).

The readers of MoKF, as represented in the letter columns, share similar tastes.

Examples: Readers of Master of Kung Fu Enjoy Other Works of Literature

Some comparisons to literature are based on this comic's deeply allusive plotlines, indicating shared reading experiences:

"I have come to the conclusion that [supporting character] Clive Reston's great-uncle was Sherlock Holmes while his father, in all probability, was James Bond" (Larry Feldman, MoKF 45).

A fan writes in under the pseudonym of the Wold Newton Meteorics Society, claiming that "the name is obvious to those who have read Philip Jose Farmer's biographies of Tarzan or Doc Savage" (MoKF 46).

Some readers compare the qualities of the Shang-Chi story to other literary works:

Mark R. Kausch sends MoKF an entire Rainer Maria Rilke poem, dedicating it to the experience of Shang-Chi (MoKF 48).

J. Marc De Matteis would compare MoKF to "Harlan Ellison, Tom Robbins, Meher Baba, etc." (MoKF 56).

Ralph Macchio compares plotlines in MoKF to "the idea of the 'absurd world' Camus spoke of in The Stranger" (MoKF 30).

Ed Via compares MoKF to "the works of William Faulkner or Tennessee Williams" (MoKF 75).

Examples: Readers of Master of Kung Fu Enjoy Other Comics

Comparisons to other comics abound. Sometimes, MoKF shines in the comparison; sometimes not, but in both cases, the standard of taste for a MoKF reader is established.

"The first issue of Master of Kung Fu was well-done and far, far better than the other current martial arts mag—Yang—which is a poor adaptation of TV's Kung Fu" (Harry Cleaver, MoKF 18).

"The character of Rufus T. Hackstabber rates with Howard the Duck" (Ann Nichols, MoKF 42).

"I see, in Shang Chi, a character that will soon rival Spider-Man and Silver Surfer in popularity" (Jackie Frost, MoKF 23).

These common tastes, revealing common reading experiences, are the grounds for an emotional connection between readers.

The Readers Respect and Interact with Each Other, Building a Sense of Membership

A sense of membership is necessary for the constitution of any community. (A community that potentially includes every other human being is a community with weak contours and weak powers to help circumscribe member identity.) For more information on McMillan and Chavis' sense of membership, click here.

There are two ways that the community of readers of Master of Kung Fu becomes a selective community, more than just "anyone who picks up this comic book." First, the common, shared tastes enumerated above become a litmus test separating the fan from the reader. Recognizing the allusions in the comic helps to establish a common symbol system. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the members of the community recognize each other. They refer to each other in their correspondence—creating a kind of positive reinforcement of common group identification.

Examples: The Readers Comment on the Letters by Other Readers

"Thanks for printing Bill Wu's latest letter; it made for some very interesting, thoughtful reading" (Ed Via, MoKF 53).

"It's about time for the return of Fu Manchu, no matter what Bill Wu thinks!" (Cat Yronwode, MoKF 76).

"Frank Lovece was right; you've reached the point of comics as cinema" (Ron Masters, MoKF 43).

A web of members of the community is created by these references. The readers of MoKF interact with each other in ways that we see echoed today in online forums and other sites of "online community"—helping cement our sense of the readers of MoKF as a genuine community of readers.

The Readers Believe that They Can Influence the Comic Book, Its Creators and Its Characters

Another key feature of a community is the belief that members can shape the community, and that the community can shape the members (for more on the proper definition of influence, click here.) In the case of comic books, this can mean a belief that the members can shape the future of the comic book and the stories therein.

Examples: Readers of Master of Kung Fu Critique the Depiction of Character Stereotypes

MoKF readers are sensitive to the representation of women and Asians in this series, and they express their desires to the creators in hopes of changing or directing representations.

"Why do women—first Juliette, then Leiko—keep betraying Shang-Chi? Isn't this reinforcing the stereotype of woman as vamp/Mata Hari or whatever?" (Deborah Calverly, MoKF 114).

"I have an abiding belief, so far fundamentally unshaken, that Fu Manchu cannot be depicted in a non-stereotyped form as long as the elements which define the character are maintained—as they must be. For this reason, I still feel that his absence is perhaps the greatest possible improvement possible in the series" (Bill Wu, MoKF 49).

Examples: Readers of Master of Kung Fu Critique the Depiction of the Lead Character

They express their approval of the characterization of the lead character.

"I had a feeling that the record Shang Chi selected would be Fleetwood Mac, and I'm glad you've given Chi such good taste in Western music" (James C. LeRoy, MoKF 58).

"Shang Chi remains the most honest character in comics" (Rook Jones, MoKF 41).

Example: Readers of Master of Kung Fu Critique Specific Creators

And, they express their approval (or disapproval) of the creators:

"[Artist] Day's evocation of Chinese imagery, architecture and symbolism, especially on the splash page, was excellent. [Author] Moench's understanding of the importance of the seasons, caste systems, and suicide in Chinese mythology was very impressive" (Alexandra Peers, MoKF 117).

This is perhaps the most important factor in considering any group of fans or collection of media consumers a "community." Shared values and a sense of membership criteria are simply not enough; there must be a sense that the actions of the community matter for the community's future.

The Readers Believe that Reading MoKF Fulfills some Social and Emotional Needs

Finally, there must be some gain from being a member of this community of readers. Scholars in media studies often refer to "uses and gratifications" in media consumption, the idea that we consume media for individual psychological and social purposes: escape, social interaction, information and education, and more. This research dovetails nicely with our working definition of community because the community of readers of MoKF does meet some social and emotional needs by reading and writing about MoKF. In the case of this comic, they gain a real sense of their own importance because they can see what others do not: the unique literary and cinematic values of their favorite comic series.

Examples: MoKF Readers Get Some Emotional Benefit From Reading MoKF

"I have absolutely no interest whatsoever in the Martial Arts, be it Bruce Lee, David Carradine, Iron Fist or Kung Phooey" (J. Marc De Matteis, MoKF 56).

"It is hard to explain MoKF. When people tell me they don't want to read it because it's just a kung fu book and they don't like kung fu, I want to say 'BUT IT ISN’T A KUNG FU BOOK… it is a genuine work of art'" (Mike Sopp, MoKF 114).

It seems clear that the readers who participated in the letters column of MoKF can be said to constitute a legitimate community, fulfilling the social psychological criteria for community in the ways that they express themselves on the letters page.

It seems clear that (despite what we typically think of as solitary activities of reading and writing) the community of readers that coalesced around Master of Kung Fu was a genuine community.

About the Community of Readers in Convergence Culture

We want to do more than simply identify the historical phenomenon of a community of readers of a single comic book. By itself, the existence of this historical community is personally interesting to David (as a kind of member of that community in his childhood). And it is personally interesting to Kate, whose research includes analyses of Asians and Asian-Americans in print culture. But really, this is the study of a niche community in a historically-remote period…

…unless we can find contemporary reverberations with fans of comics and other media in contemporary life. Communities of readers have a historical importance as a phenomenon all their own, but they have extra importance in the twenty-first century as we enter the Convergence Culture.

Henry Jenkins has defined the convergence culture as the intersection of the creative power of corporations and media institutions with the creative power of their audiences. In his 2006 monograph, Jenkins explores some case studies in convergence culture. For example, CBS has created a media powerhouse in its reality show Survivor, but fans of that show have also created a mountain of texts (most of them online) responding to, interrogating and fostering the appreciation of Survivor. Similarly, fans of Harry Potter have created a vibrant fan culture which entails both reading about the young wizard, but also extending his adventures in fan fiction.

Jenkins calls this "convergence" culture because the older media models (in which the institution broadcasts to the relatively passive, consuming audiences) are being replaced by the convergence of the creations of the institutions and the creations of the fan base across multiple media. In convergence culture, it is harder to mark the line separating producer and consumer of media text. And, in convergence culture, the productions of the newly empowered consumer advance the agenda of the institution: the websites full of fan fiction make Harry Potter more popular and more valuable. The labor of the fans advances the goals of the commodity producer.

Jenkins argues, persuasively, for the relative uniqueness of contemporary media in making convergence culture possible. But it is also clear that audiences have always, in one form or another, produced texts in response to the texts they consume. And those texts have sometimes helped advance the agenda of the corporations that generate these media. The case study in this exploratory piece for Harlot is a textbook example of convergence entirely within the old media culture.

It seems that the letters page was more than just a gift from the comic book companies to the fans—the donation of a page to the fans for their self-expression. The letters page was another place for effective marketing to occur. Through a careful selection of which of the fans' letters to print, the comics companies created their ideal reader.

Who was the ideal reader of the Master of Kung Fu? They were not your average Marvel Comics fan. While other fans were arguing about the pathos of Spider-Man's crush on Mary Jane, MoKF fans were depicted on the letters page as fans of a different breed:

- They were literate, capable of deciphering allusions as well as creating them.

- They were capable of critically reading a text they nonetheless loved for its implications for equality and cultural diversity.

- They could engage each other and the editorial staff with both passion and respect.

- They measured the quality of a comic not just against other comic books, but also against forms of "high" culture: film and novels.

- They valued the ability of a comic book to resonate with both the "real life" they shared with the characters as well as complex eastern philosophies, as they understood them.

It seems pretty clear that the tens of thousands of readers of Master of Kung Fu every month couldn't all be such literati. David was one of those readers, and he was in elementary school. The ideal reader wasn't necessarily a reality, but more likely an aspiration.

Master of Kung Fu was never a runaway success as a comic book, but it sold solidly for ten years. Its consistency stemmed in part from its quality as a comic book, but we think its loyal fans were also drawn to the particularly rarified image of who a fan of this comic would be. Fans of MoKF were an elite—something to be aspired to, among comics fans. This impression could not be created by the comic book alone; it needed a carefully edited letters page, populated by letters written by fans who craved that rarified status and sought validation from the editors and other readers that they had "made it." And once they "made it," they held that status tightly and close. The end result was a consistent sales base of committed fans.

Implications

If it was true thirty years ago that the community of readers of Master of Kung Fu constituted a genuine community that nonetheless was harnessed to serve the interests of the corporation, it seems that Jenkins' claims about convergence culture should both resonate even more fully today and serve as a warning. The fans of Master of Kung Fu wrote for the letters page to express their identities and their evaluations of the work. But the corporation ran those letters as a means of building a fan base and maintaining sales at a time when newsstands were folding and comics distribution channels were narrowing. Comics were becoming less ubiquitous, and so the fan base needed to become more dedicated.

We see similar moves among the contemporary convergence culture. Where network television dominated media consumption in the 1970s and 1980s, in the twenty-first century, NBC, ABC, CBS and FOX must share a tinier slice of the pie. Broadcast television depends on the vibrant energy of fans to make Lost and The Office must-see television. They need the energies of those fans to complement their marketing machines—to hold on to their fan base. It is not a gift from CBS that fan sites about Lost are allowed to exist despite copyright infringement; it is a an effort to harness fan energy to boost ratings and grease the bottom line.

If comics as a medium and comics fandom have "arrived," that arrival is not on our terms; it has occurred because we can be used by the corporate machine the ways that fans of other media are similarly used. We are being ushered into mass culture because we have a passion for our interests. That passion translates directly into spending, of course, but it also translates directly into energy that can be harnessed to boost opening weekend box office and spark ratings on television. That energy translates into websites, YouTube videos, and all sorts of community textual production that constitutes free publicity for the corporations who would profit from our labors of love.

If Henry Jenkins has made clear that the age of new media makes this common practice—that the conditions of convergence culture are an almost inevitable synergy between fans and corporate interest—this historical case shows that that has been the case for decades. Marvel Comics used fans of the Master of Kung Fu to boost the sames of the comics the ways that Marvel Films now uses fans of Iron Man to boost ticket sales at the box office.

There is no consolation to be had in the sense that comics fans have arrived. We are not taking our place amid the icons of popular culture because the objects of our affection are going mainstream. We are taking our place among the tools of corporate America. When will we learn? And when we have learned, how can we become responsible fans, responsible consumers of media in an environment that sees us less as people and more as free labor in public relations?

Bibliography

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

- McMillan, David W. "Sense of Community: An Attempt at Definition." Unpublished manuscript. Nashville, TN: George Peabody College for Teachers, 1976.

- McMillan, David W. and David M. Chavis. "Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory." Journal of Community Psychology 14 (1986): 6-23.

- Pawley, Christine. Reading on the Middle Border: The Culture of Print in Late-Nineteenth Century Osage, Iowa. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

- Robbins, Trina. From Girls to Grrrlz: A History of [Women's] Comics from Teens to Zines. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1999.

- ---. "Gender Differences in Comics." Image & Narrative 4. Retrieved November 17, 2008 from http://www.imageandnarrative.be/gender/trinarobbins.htm

David Beard is Assistant Professor in the Department of Writing Studies at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. His research has centered on modernism and rhetoric. His publications include Advances in the History of Rhetoric (with Richard Enos), and he is currently working on a book project on I. A. Richards.

Kate Vo Thi-Beard is a doctoral student in the School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In addition to her interests in comics and graphic novels, she is researching the role of Asian American magazines in building community and cultural identity.