Why the Duke Lacrosse Scandal Mattered — Three Perspectives

Heather Branstetter

When a controversial event forces the contemporary American public to engage with important socio-political issues that intersect with constructions of race, gender, and class, the underlying social conditions too often remain unexamined. Our public discourse instead works to sensationalize and polarize discussion of such events; as an effect, participants in the discourse engage in rhetorical strategies that rely on the emotions of indignation, anger, and blame. This essay looks back to the discursive exchanges that arose in response to the Duke lacrosse scandal of 2006. I analyze three "representative" patterns of public response, while also interpreting the cultural conditions that enabled these responses. In doing so, I highlight unproductive patterns of discourse and offer strategies that might help us to move toward more democratizing communication in the future.

In the spring of 2006, a young working-class black woman accused three young white men, members of Duke's lacrosse team, of gang-raping her. The team had hired her and another woman to come to the lacrosse players' house to take their clothes off for money. When that interaction went sour, it suddenly became a topic of conversation across the nation. Initially, I became invested in the scandal because it became such a media sensation and because it took place so close to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where I live. I remained invested in the case, however, because I was upset by the discourse that circulated in the aftermath of the case, and I believe that an effort to understand the reactions to the scandal might offer insight into a much larger and more disturbing communication problem that the American public negotiates when trying to talk explicitly about race, gender, sexuality, and social class. As I tried to come to terms with my own and others' responses to the events that took place as this scandal unfolded, I couldn't help but wonder:

What was it about this case that caused so many people to feel emotionally attached and identify so strongly with one "side" or another? What was really at stake here?One answer may seem rather obvious: mass media outlets and bloggers saw the makings of a sensational story and thus seized the opportunity as a way to bolster sales, attract an audience, increase traffic to websites, etc. They constructed a compelling narrative that gave rise to powerful emotions and snowballed toward further discourse. But what were the specific elements of this case that enabled such a response? I am motivated by the following questions: What aspects of contemporary American life did this particular cast of characters and storyline engage? Why did so many people care so much about it? And what can we learn from the discourse that took place, in order to seek more productive conversations in the future?

In what follows, I search for answers to these questions by describing three "representative" responses to the Duke lacrosse scandal, while offering my interpretation of the cultural conditions that enabled these responses. I am roughly dividing the reaction to the case into three responses, by describing the perspectives of three different producers of discourse: 1) mainstream mass media outlets; 2) advocates for "social justice," who saw the case as an opportunity to spark fresh dialogue about gender, race, and socioeconomic class; and 3) advocates for the lacrosse players who felt that white men are ongoing victims of systematic "reverse racism." I believe that mainstream media outlets recognized an important socio-cultural-economic pattern that can help us to understand the broader cultural anxieties that were brought to the surface by the Duke lacrosse scandal. I describe the narrative formula that becomes key to understanding these cultural anxieties and I then explain why the emotional investments at stake were not really about the case itself. By breaking down the discourse in this way, I hope to describe recurrent patterns that both foreclose productive public debate and continue to plague our contemporary social atmosphere. My goal is to engage others in conversation about strategies we might employ in order to facilitate better dialogue in the future.

How to Craft a Compelling Narrative: The Mainstream Media Perspective

For the benefit of readers who were living under a rock three years ago, and for those who might now be confused about who, in particular, cared so much about this case and the discussions it prompted, let me offer a brief overview of the story as it unfolded and the people who were pulled into its orbit. I believe that Newsweek's coverage offers a representative example of the way in which the case was reported by the mainstream media, and my purpose in discussing Newsweek's coverage is twofold: I seek to explain the relevant information about the case as it developed, while I am also crafting an argument about the formula constructed by most of the mass media news outlets covering the case.

The cover of Newsweek's May 1, 2006 issue featured mug shots of the two Duke University lacrosse players who had at the time been accused of the rape (a third team member was later added to the ranks of the accused). The title "Sex, Lies and Duke" accompanied the pictures. Open the magazine to "The Editor's Desk" and you find commentary from Mark Whitaker that details his reasons for featuring "the tawdry but riveting story of a lacrosse-team party gone bad, with a stripper charging rape and putting one of America's finest universities in the eye of a media hurricane." The editor focuses our attention to the more sensational aspects of the case, pointing out that we should worry about the prestigious university while offering his interpretation that his reporter, a Duke alumna, sees the case through a very personal perspective even as she remains above the fray with her "smart commentary."

The story is worth reading, we are told, in part because it involves college athletes at a prestigious university, in part because it has generated such a storm of interest, and in part because we might feel a vicarious connection to the backgrounds and motives of the people involved. Whitaker explains that Newsweek chose to put the lacrosse case on the cover because it touches larger themes: "the 'jockocracy' on so many college campuses, the tensions between 'town and gown,' the politics of race and class, and how tabloid stories inflame the media, and vice versa." In addition to these larger themes, which apparently seem to him to be inherently newsworthy items, Whitaker also instructs his readers to become invested in "the backgrounds and potentially complicated motives of the key participants, from the athletes to the exotic dancers to the local prosecutor and his political allies and foes." In short, readers are prepared to anticipate the coming article as though it were a juicy piece of gossip, a scandal in the truest way—a good crime story involving people in positions of privilege and power, featuring an interesting cast of supporting characters with as-yet-to-be-determined motives.

(Are you holding your breath for it yet?)

The article itself is titled simply, "What Happened at Duke?" and a quick glance provides another overview of the supposedly salient elements of the story: "Sex. Race. A raucous party. A rape charge. And a prosecutor up for re-election. Inside the mystery that has roiled a campus and riveted the country." Again we see the focus reduced to a saucy crime story with high political stakes and intrigue. The point is reiterated as the article starts to hit its stride; if readers had not yet received the message that the story should be devoured much like a thrilling novel, the authors go ahead and explain this aspect explicitly: "the case has provided a tawdry real-world blend of true crime, high life and low manners, for the likes of novelists John Grisham and Tom Wolfe. Raunchy rich kids. Town-gown conflict. Raw racial politics. A bedeviling forensic puzzle." We begin to see the rough outlines of the clash of binaries that might compel a reader to follow the developments of such a story.

The rest of the article goes on to tell the tale of rich white kids attending a prestigious university embedded in a poor town with a vocal black community. The reporters actively set up two "sides" of the story, even though they appear merely to be describing what happened as they quote both witnesses and the prosecutor, while detailing the defense's timeline. In doing so, the authors effectively place the reader in the position to identify with one of these two sides that they have constructed. The case, the reporters explain, "is no laughing matter to the young woman who suffered injuries that appear to be caused by a sexual assault. And to the family of Reade Seligmann, one of the two players indicted last week, the whole affair must seem like a grotesque nightmare." The reader receives the message that this construction of binaries does not only involve the abstract concepts of black vs. white, poor vs. rich, woman vs. man, and a struggling community vs. a privileged university. No, it also lines up real people on both sides of the binary and provides the rhetorical resources for the reader to see how these people have been victimized by the situation. The reader then sympathizes with (or fails to sympathize with) either a poor black woman from Durham who appeared to have been raped or the white men from rich families attending a prestigious university—and their horrified families.

Why does the discourse, broken up into these binaries, encourage the audience to identify with one side or another? Why does this matter? It is only when we begin to personalize the story that we readers best recognize what is at stake, at which point we become emotionally invested (or not) with one side's perspective and say to ourselves: what if that were me? In the case of the Newsweek article, for example, a reader who has identified more with the side of the lacrosse players' families and personalized the stakes would then decipher the ominous warning that this could happen to you—your innocent college boy could also be accused of raping a black stripper. You might one day find yourself embroiled in a similar state of crisis.

The article wraps up with a series of disturbing quotations, providing further emotional fuel for whichever side the reader has by now surely chosen to identify with. Readers who have identified more with the accuser's side of the binary—associated with poor, black, woman, and struggling community—can take comfort in the fact that the events have prompted the university to engage in dialogue about whether or not Duke promotes "a culture of crassness at the expense of a culture of character." But then these readers can also become frustrated when they read that not very many students showed up for the dialogue, and they can read about how the university is profiting from those who are suddenly buying lacrosse jerseys to show their support for the accused players. Those who have personalized the perspective of the "alleged victim," as she is called, can feel hurt and then burn with anger upon reading a portion of an email sent out by one of the team members an hour after the dancers left, detailing how "he wanted to hire some strippers and skin them and kill them while he ejaculated in his 'Duke-issue spandex.'" As a result, those reading the article who might have chosen to identify with the accuser instead of the lacrosse players receive confirmation of what they thought they already knew: rich white guys are assholes who were born into unearned privilege, get to attend exclusive colleges where they don't care about whether black women get raped or not because they think that they are better than everyone else and entitled to do (or have, or humiliate) anything (or any one) they want.

The reporters close by offering a look "across town" to the "mostly black" college of North Carolina Central, where the accuser was a student. Now we read about the reporters' commentary that these (supposedly black) classmates seem "bitterly resigned to the players' beating the rap." Readers who line up on the accused players' side of the binary—associated with white, male, privilege, and Duke—can be indignant that one NCCU student claims: "This is a race issue." She comes across as resentful of the fact that the lacrosse players "have a lot of money on their side." Those who have personalized the perspective of the accused players can also burn with anger when they read another student saying that he "wanted to see the Duke students prosecuted 'whether it happened or not. It would be justice for things that happened in the past.'" These quotes are fuel for confirmation of what those lined up on the lacrosse players' side of the binary thought they already knew: the black community plays the race card and is resentful of those who have money and privilege, and they continue to falsely blame white men for things they didn't do.

The construction of the above compelling narrative relies on a relatively simple yet obfuscated formula, and we can break down the rhetorical strategies that enable the formula into four steps:

- Sell the story as sensational and worthy of a juicy read.

- Construct binaries based on race, gender, and social class. White, man, privilege, Duke, and lacrosse player go on one side of the binary. Black, woman, poor, the Durham community, and accuser/stripper go on the other side.

- Articulate what is at stake for each side of the binary by casting each in a sympathetic light and thus making it possible for either side—but not both sides simultaneously—to be seen as victims. This step encourages the audience to identify personally with either the perspective of the accuser or the accused and thus line up with one side of the binary or another.

- Offer disturbing quotations and facts to elicit powerful emotional reactions, so that the audience can further personalize the victimhood and are provoked to feel injured by and angry with the other side. This personalized hurt-turned-to-anger, and causes the audience to emotionally cluster together everything that lines up on the other side, so that they become angry at everything associated with the other side.

From the perspective of those in the mainstream media, this formula makes sense because it is effective, and because there is the economic incentive to craft compelling narratives. Plus, this incentive has been amplified by the more recent development of the 24-hour-a-day news cycle and improved Internet access to immediate information. Thus, reporting the news has increasingly become a moneymaking venture, driven by an ever-present anxiety that mainstream media outlets will soon become irrelevant. The sensationalism draws in the audience, whose personal emotional investment ensures their continued interest in the outcome and engagement with the discourse. My discussion here has taken Newsweek as an example, but most of the other narratives at the time were also crafted using similar rhetorical moves (although the formula could—and often was—adjusted in order to better reflect each media outlet's own audience perspective).

But what have been the effects, in terms of public dialogue? How have these kinds of rhetorical moves affected how we communicate with and relate to one another (or fail to)? Since audience members initially chose to identify with the perspective they already felt more sympathy for, and because they are engaged in the binary emotional clustering and personalized hurt-turned-to-anger, it becomes extremely difficult to empathize with or try to understand anyone or thing that lines up on the "other side." Thus, it becomes easy to make new and unpleasant associations about the other side, in terms of race, gender, and socio-economic class. If the audience already had pre-existing assumptions about the other side (and they probably did, because that's what the media outlets are tapping into), it also makes it easier for the audience to believe that they have received further confirmation of said assumptions, in terms of race, gender, and socio-economic class, regardless of whether or not those assumptions are true, and regardless of whether or not the audience is consciously aware that this phenomenon is taking place.

I don't believe that this phenomenon is the media's "fault" per se. It is not very useful to blame them, since they have the (powerful) economic incentive motivating them to engage their audience in this way. And I also don't mean to imply that the reporters involved "created" some sort of emotional feeling that wasn't already present. Rather, I believe that they were simply very good at recognizing the pre-existing cultural and political conditions that they could tap into, in order to ensure that the story resonated with their audiences. Such narratives, however, serve to continue the cycle and perpetuate the pre-existing patterns. The rhetorical moves involved in the construction of these narratives also become key to understanding how the case helped to capture the collective imagination of the American public. While most of us obviously don't find ourselves positioned neatly on one side or the other of the binaries constructed, the effect of the discourse was such that two "sides" clearly emerged, and these binaries made it impossible to side with both sides simultaneously. Many people did personalize the lacrosse case and were caught up in the cycle of feeling victimized and the hurt-turning-to-anger possibilities that the story brought to the surface. Below, I attempt to offer a charitable reading of two "representative" examples of both perspectives that emerged in the aftermath of the scandal.

Seizing the Opportunity to Spark Dialogue:

The Perspective of Advocates for Increased "Social Justice"

I should preface this section by explaining that I initially found myself aligned along the side of the binary I will here describe; that is, the side of the binary associated in the same emotional cluster as the accuser. Also, I did not confidently believe that the lacrosse players were guilty, but I thought that it could be pretty likely. Why would I think this? The wealth of social critique available that discusses systemic sexism, racism, social class conflict, and homophobia, has persuaded me that the issues raised by the lacrosse case continue to matter. As a member of the academic community who studies social movements, I am already intimately engaged with scholarly work that documents the need for us to work toward rectifying historical (and ongoing) problems of social inequality. Because I am already aware of the ways in which rape is an ongoing problem for women in general and because I recognize that African American women in particular are more likely to be sexually assaulted and less likely to be believed, I found myself personally sensitive to the accuser's side of the binary, and I was upset about how the narrative formula worked to associate sexual assault with titillation, and encourage us to read the story as entertainment, rather than take it as a jumping off point for a more serious discussion of the ongoing and widespread problem of race dynamics in combination with sexual violence against women.

I am also aware of how isolating, frustrating, and dehumanizing it can be to feel coerced into silence, or to feel like your pain goes unacknowledged by others, except when it affects those who are higher on the socio-economic ladder of power. Charlotte Pierce-Baker's accessible book, Surviving the Silence: Black Women's Stories of Rape, attempts to give a voice to the many women who feel that they cannot share their stories, women who are survivors of rape, but who choose "to live in some degree of secrecy, to protect themselves from censure, to stave off family discomfort and worry, or to protect those they have been conditioned to believe are African American 'brothers'" (19). This book also helps us to understand why it matters to stand as an advocate in support of another who feels silenced. By doing so, we offer important acknowledgement that another person's pain matters, and that he or she has been understood. Those advocates of social justice naturally aligned on this side of the perspective because they feel an ethical imperative to offer a supportive counterpoint to the dismissive wall of silence and apathy that women, minorities, queers, and the poor often perceive. They also, however, often believe that those positioned on the other side of the binary, as white and male, often born into privilege, are implicated as a part of the problem, regardless of whether or not they might personally "deserve" to be found blameworthy.

Why? Because white men continue, at a disproportionate rate, to occupy positions of relative power and they therefore control the majority of the political and social discourse. They set the agenda, and have the power to determine which issues matter (and which ones do not). A quick look at the present and historical composition of our country's leadership—members of the Congress, Supreme Court, and the President—can support such a claim. Recent events suggest the tide might be turning, and yet, 106 of the past 111 Supreme Court justices have been white males, while 43 of the past 44 presidents have been white males. For those who worry that women and minorities control the discourse in our universities and colleges, a quick peek into the ranks of academia reveals that white men also continue to occupy relative positions of power even in higher education. A recent report published by the AAUP highlights the ways in which "women are still underrepresented in academic leadership positions, both absolutely and relative to the eligible pool of tenured women." Colleges do not do a very good job of retaining minority students through graduation, and as recently as 2004, whites were found to "hold more than 89 percent of highest academic posts." These problems are also reflected in the mass media—where the majority of editors, producers and others in positions of power are white men (with the very visible exception of Oprah). Yes, I am here only pointing out a lack of "representation" in terms of skin color and gender, and this argument glosses over important points that I will address below in the third section. However, the point remains: those who found themselves positioned on the side of the binary that the accuser also occupied believe race and gender continue to be salient issues, and that these issues are often dismissed or not taken seriously by those who control the discursive agenda (and who, according to the binary logic of emotional clustering, are also white and male).

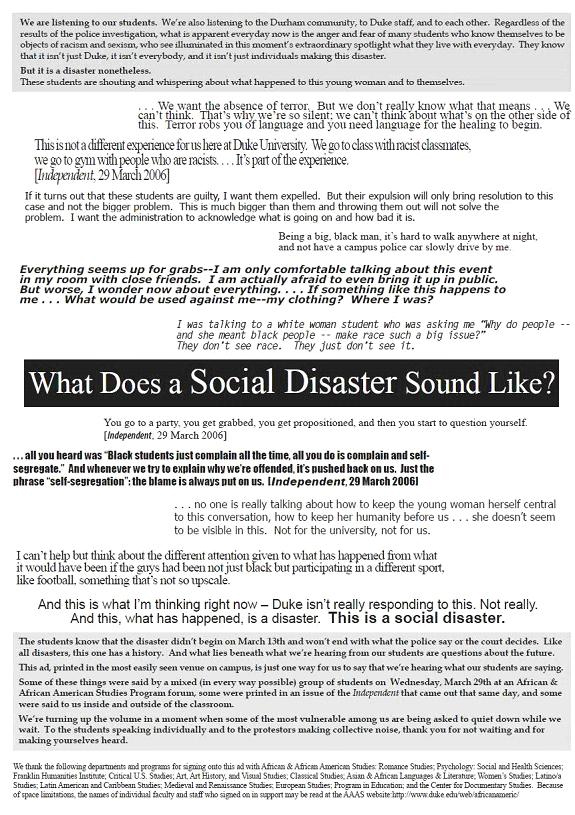

An understanding of this context, in terms of perspective, can help us understand how and why advocates of social justice responded to the lacrosse scandal (and the narrative formula constructed by the mainstream media) in the way that they did. In the frenzied aftermath of the initial accusation, a group of Duke faculty members, now infamously demonized by advocates of the lacrosse players as the Group of 88, took out a full page ad in the university's student newspaper. The center of the ad features bold white type that stands out against a black background. It asks, "What Does a Social Disaster Sound Like?" The rationale for the ad is provided at the top of the page, and further commentary is offered at the bottom. In their commentary, the professors explain: "We are listening to our students. We're also listening to the Durham community, to Duke staff, and to each other. Regardless of the results of the police investigation, what is apparent everyday now is the anger and fear of many students who know themselves to be objects of racism and sexism, who see illuminated in this moment's extraordinary spotlight what they live with everyday." A photo of the "Social Disaster" ad can be found here, and it is pictured to the left. In another document, titled "An Open Letter to the Duke Community," the faculty members claim that the intention of the ad was to provide "a call to action on important, longstanding issues on and around our campus" and they explain that they were trying "to give voice to the students quoted, whose suffering is real."

These professors found themselves positioned alongside the accuser, in terms of the binaries at work. And so, regardless of whether or not the professors in question presumed the guilt of the lacrosse players, the emotional effects of the binary was such that it didn't matter: by identifying more with those who have been subject to racism and sexism, the professors who endorsed the ad were also implicated alongside the accuser and thus positioned in opposition to the lacrosse players' perspective.

In the ad itself, we see quotes from students testifying to their perceptions of the hostile socio-cultural conditions they face. The quotations appear to be oriented toward using the lacrosse case as a jumping-off point for more general discussion about race, gender, sexuality, and socio-economic status. The bottom of the page explains that the ad, "printed in the most easily seen venue on campus, is just one way for us to say that we're hearing what our students are saying," and it concludes with the statement, "We're turning up the volume in a moment when some of the most vulnerable among us are being asked to quiet down while we wait. To the students speaking individually and to the protesters making collective noise, thank you for not waiting and for making yourselves heard." These last statements are, to me, the most provoking aspects of the ad, and indeed, seem to have inspired the most ire in the backlash of reaction to the ad. In my reading, this ad was intended as an appropriate gesture of solidarity, since it spoke to those students for whom the coverage of the lacrosse story might have triggered latent trauma, forcing them to feel anew the traumas of the past, or to begin to reconcile ongoing trauma they had yet to come to terms with.

The ad also served the purpose of generating new discussion, intended as it was to give voice to conversations that were already taking place, conversations that might spark further dialogue about race and gender, conversations that most university students embrace (regardless of their political beliefs), because they recognize the ways in which a college can offer a rich venue for engaged, if difficult, discourse. The departments and professors endorsing the ad recognized the ways in which the media coverage and the ensuing discourse might be offensive and hurtful to "some of the most vulnerable among us," and they sought to become advocates for those who are so often silenced or coerced into silence by an unresponsive political and social atmosphere. According to my own interpretation, most of the quotes featured in the ad testify to the general feeling that "nobody can hear us; I wish someone would acknowledge my pain." One of the motivations for posting the ad probably stemmed from the professors' awareness that the case would not have been so widely reported had it not involved white men, born into privilege, and so they seized the opportunity to draw further attention to the plight of those frustrated by systemic social inequalities. I share this perspective because I too am frustrated by a culture that is too often unable to recognize and respond to pervasive social problems because they are most likely only to rise to the surface when they affect those who are in positions of privilege. And because the people who are in positions of relative power already control much of the discourse, they have plenty of advocates who come out of the woodwork and make lots of noise.

And that is exactly what happened.

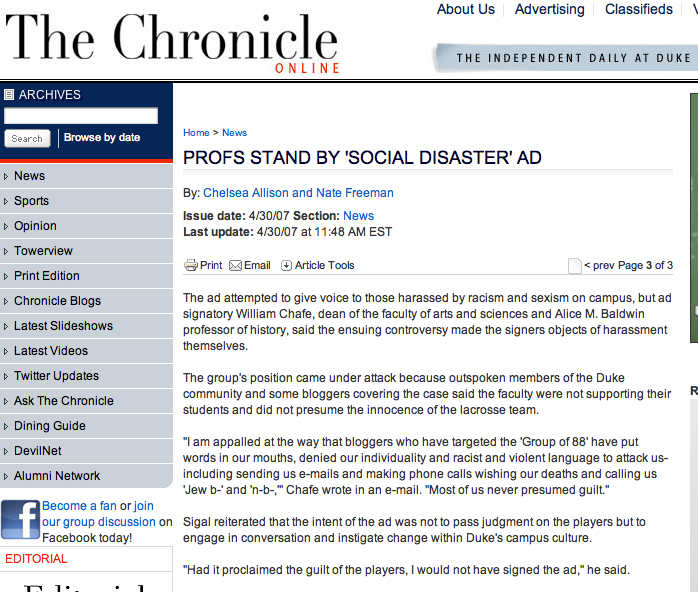

As the Duke student newspaper has reported, in an article titled "Profs Stand By 'Social Disaster' Ad," the faculty members who endorsed the ad came under severe criticism from many fronts, and have even received threatening emails and phone calls from those who did not read the ad in such a charitable manner (more information about this phenomenon can be found here). Anyone who now talks about this case in a way that aligns with the perspective of the Group of 88, especially people who teach at the college-level, also become new targets for criticism and charges of "reverse racism." Why is that? Because the ad failed to acknowledge the perspective of the lacrosse players' side of the binary, those who aligned with them felt unacknowledged and hurt. As a result, they felt like the Group of 88, who supposedly stood for social justice, were hypocrites. Because the ad aligned with the accuser's side of the binary, those who endorsed it were, by association, guilty of also accusing the lacrosse players. Thus, advocates of the lacrosse players found the ad to be evidence of the professors' presumption of the lacrosse players' guilt, regardless of whether or not that was the intention.

Feeling Blamed for Crimes You Didn't Commit:

The Perspective of the "Everyday White Guy"

Why does it matter whether or not the Group of 88 professors and other advocates for social justice (i.e., Rev. Jesse Jackson) may have presumed the guilt of the lacrosse players when the justice system won out in the end and found them innocent? Why would it matter whether or not the court of public opinion rushed to judgment (or might have thought that it was irrelevant whether or not they were actually guilty)? To those who identified with and personalized the lacrosse players' point of view, it mattered because everyday white guys feel like they get blamed all the time for things that they didn't do. Who are these "everyday white guys" I'm talking about? These are the white men who believe that it is not fair that a university campus has a Women's Center and not a Men's Center (and who fail to acknowledge the point that historically, the whole university has been a Men's Center). These everyday white guys are the ones who feel like advocates of social justice in the university are indoctrinating their students in "white male bashing." These are the guys who feel like they have been held personally blameworthy for the fact that historically, white men have been born into privilege and so get blamed for things that aren't their fault, especially when said white men do not, themselves, belong to a privileged economic class (or have access to the kind of cultural capital that usually coincides with economic wealth). They feel as though advocates for social justice too often dismiss the cries of those who feel as though it is open season for attacks on white men. These righteously angry White-Male-Americans are often perfectly nice people, not inherently racist, or misogynist, and they usually are not rich. If they have monetary success, they believe that they earned that success through their own hard work, whether or not that is actually true. "I can't help it that I'm a white man," they say, "why should I shoulder the blame for a politicized identity that I didn't choose, based on my race and gender? Isn't that racism itself? Isn't that sexism at work?" This might be where I would respond, "well, yes, systemic racism, classism, sexism, and homophobia hurts everyone, including you."

Okay, but there are two items that are key to understanding the perspective of those who aligned with the side of the lacrosse players and their families, and it is important to understand these points if we are to recognize the forces at work here.

- Since the wave of new social movements that swept through America during the 60s and 70s (i.e., the civil rights movement, women's movement, and gay liberation), people who are heterosexual white males—the everyday white guy—have felt their historical power slipping away, and they feel intimidated and worried about this. Why? When you let everyone into the country club, it's not a country club anymore. As a result, they worry that they are increasingly becoming shut out of the kind of access to power and economic prosperity that people who were both white and male enjoyed during the years previous to the movement of movements (and, as I believe, continue to enjoy). That's the obvious part.

- The part that is more nuanced is this: the terms "white" and "male" are, to some degree, obscuring the picture. They matter, on the one hand, because they are the most visible markers of identity. And these visible markers, according to our binary logic and pattern-seeking brain, usually accompany privilege. That is—usually people who are white and male are comparably better off, socio-economically, and because they have held the power historically, a whole host of advantages goes along with that. On the other hand, white men alive today were not personally responsible for the creation of the pre-existing system from which they benefit. Because there are so many different axes of oppression and so many different axes of privilege, it is almost impossible to sort out earned from unearned privilege, and so these White-Male-Americans believe that they are not getting justice in the court of public opinion. Poor white men and gay white men also get pulled into the mix, even though they are not benefiting from the pre-existing system in the same way. It is not a coincidence that the everyday white guy, who is not necessarily privileged economically, would particularly identify with the lacrosse players' plight—these everyday white guys perceived the lack of initial acknowledgement that these guys might not be guilty. And it mattered to them.

So, how did this pattern play out in the discourse circulating around the lacrosse case? Well, for one example, we can look back to the media's widespread reports that those on the other side of the binary should be found guilty, whether they deserved to be or not. In the Newsweek article, we find the fuel for this fire located in the comments made by Rev. Jesse Jackson and one or two of the NCCU students quoted at the end of the article. If we look again to the "social disaster" ad above, we see how the professors claimed to be listening to their students, but they did not feature quotes by anyone who appeared to share the perspective of the lacrosse team members. Thus, the professors and university programs who endorsed the social disaster ad of the Group of 88 (and, as far as I can tell, other feminists, anyone who works toward ending racism, or anyone teaching race, gender, or sexuality studies in the academy) become hypocrites, uninterested in "real" social justice because they ignore and fail to acknowledge the plight of the innocent everyday white guys.

So who, specifically, involved in the lacrosse case discourse, are representative examples of these White-Male-Americans who identified with and advocated for the lacrosse players? Those who are curious can check out "KC" Johnson's blog Durham in Wonderland. Johnson, a professor himself, has been a very vocal voice throughout the Duke lacrosse scandal. Johnson and his readers are deeply embedded in the legalistic details of the case and have also identified the prosecutor as one of the main perpetrators aligned on the other side of the binary. There are many other blogs like his, which Johnson links to on his website. In the aftermath of North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper's announcement that the lacrosse men were innocent, Johnson also released a book which he co-wrote, titled Until Proven Innocent: Political Correctness and the Shameful Injustices of the Duke Lacrosse Rape Case. Other books, basically arguing the same points, appeared around the same time. One is titled, A Rush to Injustice: How Power, Prejudice, Racism, and Political Correctness Overshadowed Truth and Justice in the Duke Lacrosse Rape Case and another's title reads, It's Not About the Truth: The Untold Story of the Duke Lacrosse Case and the Lives it Shattered. In these titles, we see the focus on victimhood and the displacement of blame onto the side of the binary aligned with the accuser. The real victims are these lacrosse players not getting a fair hearing—they are victims of "shameful injustices," racism, political correctness, and those who are resentful of privilege. A glance at these titles alone tell us how the lacrosse players' lives have been "shattered" by identity politics, feminism, and playing the race card. These blogs and books provide good representative examples of the broader social and cultural forces available for the mainstream media reporters. The reaction from the perspective of the White-Male-American celebrates the fact that the real victims of the case turned out to be the lacrosse players and not the poor black woman from Durham. Thus this side of the narrative also has the benefit of artistic and emotional appeal—it is a satisfying end to the story for the everyday white guys who identified with the lacrosse players. For Americans who shared this perspective, the scandal provided a concrete and very visible instance in which straight white men were victims of those advocating greater "multiculturalism."

In their response to the case, however, some of these everyday white guys have also provided a very tangible example of this righteous anger taken to an extreme and unfortunate level, which makes it almost impossible to even attempt a dialogue. Historian blogger, Tenured Radical (aka Claire Potter), attempted to do so and encountered coercive intimidation tactics, ad hominem attacks, and general web nastiness. "Dr. Radical" has written about her difficult attempt to engage in reasoned dialogue in the interest of understanding those with whom she disagreed. Dr. Radical also offers what I interpret as a charitable attempt to understand the perspective of those who identify with Johnson and the lacrosse players. Her post, "The Sally Hemings Perplex; or, What Do We Know When White Men Need to Be Protected from Black Women?" has influenced my thinking on this case, primarily because she guesses that there might be more complex social class anxieties at stake, as she analyzes the narrative of the Duke lacrosse case, with special attention to this phenomenon of coercive web metadiscourse.

Why are these guys relying on such tactics? Many white men feel indignant, hurt, and victimized, because their perspective is not acknowledged by those who are advocates of social justice. And then when the White-Male-American perspective does get acknowledged, the everyday white guys often fail to recognize it (or admit it), either because they are so caught up in the emotional binary clustering, or because they feel desperate and worried that their path to economic prosperity will be closed off by affirmative action and university professors and departments who are indoctrinating their students in the art of white male bashing. According to those who identify with the lacrosse players, the Duke professors and university departments who endorsed the "social disaster" ad were blaming the wrong people. As a result, these everyday white guys believe that the other side is resentful of them, and some of them certainly are. Since the civil rights era new social movements also enabled gender studies and critical race studies, some of these everyday white guys have taken to nicknaming them professors of "angry studies." (Let me also just insert here that these guys have probably also not actually taken a class from an "angry studies" professor, although Johnson does provide selective readings with interpretive commentary over at Durham in Wonderland.) Obviously, this perspective is not limited to those who are white and who are also men; one can find many defenders of the White-Male-American identity who are not, objectively speaking, white men, and one can also find many white men who are vocal advocates for women, minorities, and queers. And even though these White-Male-Americans now feel like an ethnic minority, it is difficult for advocates of social justice to validate the concept of "reverse discrimination," of course, because the concepts represented by the terms white, male, middle-class, heterosexual, able-bodied, etc., remain the default categories in this country, the "neutral."

And yet, as the everyday white guy response to the Duke lacrosse case and its construction in the media shows, many white males and their advocates are already engaging in the same kind of rhetorical strategy that they believe advocates of social justice have been using. That is, those who I would call White-Male-Americans feel like feminists are always "playing the gender card" and members of the black community are always "playing the race card." Because they feel victimized by "angry studies," however, they are angry right back at them and the perpetual narrative construction as it plays out in mainstream media helps make it incredibly difficult to understand the perspective of advocates for social justice. Because these everyday white guys feel as though their perspective has not been acknowledged, they continue to feel victimized and so they have begun to co-opt the strategy of other oppressed ethnic minorities in order to achieve the same discursive end—to argue that white males themselves also might be considered an oppressed ethnic minority. Of course, people like me, and other advocates for greater social justice for all people, see this strategy as a parody, because the White-Male-Americans believe that "angry studies" professors and other advocates for social justice are blaming white men personally. But the everyday white guy is not necessarily personally blameworthy, aside from being complicit in the maintenance of the pre-existing social order. That is, those who would belong to the ethnic category of White-Male-Americans did not personally create this system that gave them their privilege, regardless of the fact that many of them continue to benefit from it. And some feminists and critical race theorists actually do blame them personally. Nevertheless, the white-guy-as-ethnic-minority strategy still appears parodic because those who were sympathetic to the lacrosse players are reacting to our reaction to the continued and systemic white male privilege. Wait, what was that I just wrote? That's right, the "angry studies" professors would respond that white men and others who complain that they are victims of reverse discrimination are, in fact, victims of themselves.

What's more, White-Male-Americans who claim to be victims of reverse racism also lack the vocabulary to discuss the injuries done to them. They feel that they have been stripped of the ability to speak about their plight, lest they get accused of racism, sexism, etc. Why do they feel this way? In part, it is because advocates for social justice have made such a persuasive argument that the problem is itself white male privilege, and they have implicated White-Male-Americans in the argument as benefiting from it and helping to maintain it. In a way, those who feel that they have been the victims of "reverse discrimination" lack a tangible villain, and yet they also do not feel that they can proclaim "white male power" (again, because they would be accused of racism and sexism). Instead, they have chosen to embrace the strategy of other ethnic minorities—in doing so, they too, can be victims and thus earn the entitlements (sympathy, innocence, and righteous anger) that such a title bestows.

Conclusions: Possibilities for More Productive Future Discourse

We are currently embroiled in a useless pattern of communicating with one another, and I worry that we might all be too angry at one another to come up with a solution. So my purpose here was to describe that useless pattern and the cultural possibilities that help to keep it going. The pattern, found in the media formula of the sensationalized construction of polarized discourse that lumps everything together into binaries is a big part of the problem. Of course, it is difficult to make this problem go away because it is at the heart of our brain's learning process—we categorize everything according to either/or and this/not that, as opposed to recognizing multiplicity. We see the more visible markers of race and gender, and fail to distinguish that the pre-existing socio-economic conditions and worries about future economic prosperity mean that people do not often neatly align on one side of the binary. And yet we persist in our failure to recognize that economic status is often more influential than race or gender (but which inevitably get pulled into the picture). These factors couple with the fetishization of victimhood and the emotional patterns of hurt-turned-to-blame/anger and displaced onto the "other side," which then becomes incredibly difficult to empathize with.

Because better communication requires better dialogue, which requires listening, which requires empathy, we need to figure out how to hear one another better and then construct new patterns that benefit our shared interests. As we can see by analyzing the two perspectives that this media formula has tapped into, the fundamental problem is that the systematic socio-economic incentives of the two perspectives do not line up because the pre-existing system continues to create victims out of both sides while continuing to privilege one. And as long as white males also benefit from such pre-existing socio-political conditions, they remain invested in the maintenance of the current power structures. Thus social justice advocates feel victimized because their side has historically been aligned with poverty, but the most visible markers of that poverty lead them to associate the white man with their pain. White men are also victims because they feel personally blameworthy for a system they did not personally create, even as they continue to benefit from this system and thus remain invested in its maintenance. Meanwhile, both sides displace their righteous anger onto the other, instead of recognizing the bigger problem.

I'd like to close by pointing us toward possibilities for the future. It seems to me that if we take several very tangible steps, we can eventually overcome this apparent impasse. First, we have to let go of our anger by recognizing why the binaries in our discourse fit together and then figuring out how they also work to obscure difference. This recognition can help us to stop personalizing the discourse and rejecting the feelings of blame, and anger. In doing so, we might better hear the perspectives of others, recognize where they coincide, and engage in real dialogue to sort through our differences.

What might be the outcome? If the "everyday white guy" didn't blame those who are culturally or socially progressive for their condition, they would find that their rhetorical strategy in fact, can potentially be seen to occupy the same position, oriented against a bigger villain. If the advocates for social justice would better recognize the economic incentives at stake, then they could better articulate how the lack of more systemic change at the socio-economic level victimizes all races, genders, and sexualities. Maybe then more everyday white guys would help make it happen. I have tried to demonstrate how a fresh perspective on the Duke lacrosse case becomes a helpful way to see that we are all victims of the same enemy; and this enemy is white male privilege (but not necessarily privileged white men personally) as it has been institutionalized in our systems of government, the media, and capitalism, all of which remain invested in resistance to change. With better communication, we might better understand a shared perspective and might hope to adjust these systems so that they better respond to that shared perspective. The creation of this new narrative structure—two rivals coming together to fight a greater evil—would lead to an even more satisfying ending, both artistically and emotionally.

Acknowledgements

Thank you so much to Risa Applegarth, Sarah Hallenbeck, Chelsea Redeker, Stephanie Morgan, Erin Branch, and Jordynn Jack for reading and responding to earlier drafts of this article.

I am a doctoral candidate, teaching fellow, and graduate assistant director of the writing program, in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at UNC-Chapel Hill. I specialize in rhetoric and composition, especially collective invention, women's historiography, public memory, theory, and queer rhetorics.