Crafting Change: Practicing Activism in Contemporary Australia

Tal Fitzpatrick and Katve-Kaisa Kontturi

This article brings together thoughts and practices of two Melbourne-based women working across the fields of craftivism, practice-led research and contemporary art history. While introducing and analysing Australian craft(ivist) projects, this article also suggests new concepts useful in tackling the contemporary phenomenon of craft activism.

When understood conventionally, activism is regularly associated with loud and ardent messages, outspoken charismatic leaders, and forms of protest such as mass demonstrations, processions, rallies, strikes, and sit-ins. These actions are often seen as too confrontational and antagonistic, as well as futile, as they are understood rarely to result in the outcomes hoped for (Corbett, 2013). Simultaneously, online activism has exploded, with great numbers of people turning towards digital strategies such as e-petitions, social media awareness-raising campaigns, crowd-sourcing, and online fundraising for acting on their values. However, while these forms of digital engagement attract a significant number of people, some question how well online activism translates into real-world action. The growing skepticism around the possibility of driving real-world change using online strategies alone has given rise to terms such as “clicktivism” and “slacktivism” (Parks, 2013). These terms further emphasize the need to activate activism anew, to find novel ways to engage people with issues of social, political, and environmental justice.

In the context of this shift away from both antagonistic and entirely digital forms of activism, we have witnessed the emergence of a new form. This peculiar form of activism looks to affect real-world change through a movement that combines the principles of social, political, and environmental justice with individual creativity, the act of making by hand, the power of connecting with other like-minded people, and a spirit of kindness, generosity, and joy.

The movement we speak of is craftivism!

Over the past ten years craftivism has gained global traction: individual creations, craft collectives and large-scale projects have received a lot of attention both within and outside the world of activism. The movement encompasses different entanglements of craft and activism, from knitting scarves for the homeless (SWAP; Knitting for Brisbane’s Needy; KOGO), making quilts for children in hospital (Inspiration Quilts, 2014; Quilts for Kids, 2015; Victorian Quilters Inc. Australia; Blanket Lovez, 2015), claiming the streets for women (Just, 2014), and yarn-bombing tanks (Moore & Prain, 2009), creatively reusing marine waste in order to drive a thriving social enterprise in Kenya (Sole, 2015), or making fluffy toy vaginas and flinging them over power lines as a strategy for challenging the censorship of female genitalia (Corbett, 2014). Driven by the notion that sustainable change comes about as a result of the compound effect of many small actions and ideas that over time become a groundswell of opinion, craftivism looks to engage with anyone and everyone in conversation and reflection around critical issues and wicked problems.

Margaret Mayhew with her rugs at the Refugees Are Welcome rally, October 2014. Photo: Katve-Kaisa Kontturi

Our essay situates itself in contemporary Australia, where questions of postcolonialism and multiculturalism—especially the treatment of Indigenous people, asylum seekers, and immigrants—are burning. Other popular craftivist issues encompass gender and climate change. These are the issues around which the craft projects we introduce in this essay have been created. Our contribution is both practical and theoretical. It draws on personal experience with and participation in a selected set of craft projects, and, using these as case studies, rethinks and widens the concept and practice of craftivism. This approach means that any theoretical or conceptual suggestions we offer grow from the practices of making.

Also, our positions within the field of craftivism are multiple and thus offer us a rich starting point for evaluation. Tal Fitzpatrick is a textile artist, craftivist, and community development worker currently undertaking a practice-based PhD on Craftivism and the Political Moment. Katve-Kaisa Kontturi, for her part, is a research fellow and curator interested in how fabrics—including knitted, crocheted, and stitched ones—can facilitate cultural relations.

To locate our work in the political landscape of Australia and to illustrate contemporary craftivism, let’s start with a practical example. Knit Your Revolt is a voluntary, Australia-based network of crafters that aims to raise awareness around issues relating to gender and the treatment of asylum seekers by the current right-wing, neoliberal government headed, until very recently, by Tony Abbott (Australia’s Prime Minister at the time of writing. He was deposed this month in a leadership spill). Knit Your Revolt operates as a loose network of “rad crafters” who are not aligned with any political or other organization, but instead get organized via social media. Over the past two years their knitted protest banners, public performances, and crafty interventions have been causing a stir in several major cities across Australia, including Canberra, the nation’s capital.

Two craftivists from Knit Your Revolt hold up knitted banners in front of Parliament House in Canberra, February 2015. Photo: Knit Your Revolt, https://www.facebook.com/KnitYourRevolt

In March 2015, on International Women’s Day, Knit Your Revolt infamously crashed an official Women’s Day even—hosted by then-Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who was also the Minister for Women—bafflingly held at a men’s-only club in Brisbane (SBS, 2015, Mar 6). The activists organized a creative parade to turn up at the venue. Women and men adorned in colorful knitted balaclavas, beards, and chains held up signs that read: “Minister for Women: Not in my name!” and “Knit Your Revolt: Chain Gang of Broken Hearts and Dreams” (SBS, 2015, Mar 6). The protest achieved national media coverage and resulted in a broader debate around misogynist politics.

Through their integration of craft and adversarial political activism, Knit Your Revolt has been able to create a space where dissenting voices are not so easily closed down or dismissed by the media. Indeed, the group has been repeatedly successful in gaining positive media coverage and support for their campaigns. The ability to use craft to soften the blow of dissent is a unique strength of the craftivist movement. As UK artist, activist, and craftswoman Inga Hamilton (2010) explains, “All over the world, activists take a stand against moral injustice and social inadequacies. The very nature of fighting for justice can lead to aggression and tense situations, and artwork can bring powerful, positive messages to the community, but when craft gets involved, it seems to soften the blow so the message is both more heartfelt and quick-witted” (p. 27).

The craftivist projects introduced and analyzed in our essay are concerned with this softening, engaging power of materials and processes of making. Some are more outspokenly political than others. However, all rely on the idea that small and soft actions can lead to political change.

Tal will begin by introducing some of her symbol-filled soft wall hangings and continue by drawing a connection between her grandmother’s textile art and her own current craftivist practice, as well as discussing their specific means of political action. Then Katve-Kaisa will reflect on her experiences of participating in two different craft-based workshops that perhaps exceed the boundaries of traditional activism. In this way, our essay widens the understanding of craftivism, both in terms of its history and as a mode of activist practice.

Tal Fitzpatrick at the Black Friday rally, Melbourne, March 2015. Photos: anonymous via Black Friday Rally Facebook page.

Making Space for Opinion | by Tal Fitzpatrick

My craftivist practice is strongly grounded in the feminist history of using textile art as a strategy for political action. Like countless women before me (Perry, 1999), I use textile-based craft practices such as appliqué quilting and embroidery to create objects and artworks with a message. For me, the power of these craft objects lies both in their aesthetic, tactile qualities and in the fact that they are, in many ways, everyday functional objects. This power is amplified by the subversive use of crafts, and their association with feminine domesticity and private life, to comment publicly upon politics, power, and public life—all of which are traditionally associated with masculinity (Parker, 2010).

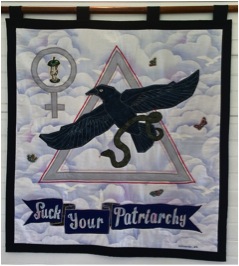

Recently, I made two quilted wall hangings: one with the words “No Justice No Peace” appliquéd onto it as a response to the #BlackLivesMatter campaign, and the other with the words “Fuck your Patriarchy.” I was compelled to make these works because of an overwhelming sense of outrage and despair in the face of current world events. As a maker, creating these works provided me with an avenue for addressing my own feelings of helplessness. Through the process of making, I find that I’m able to channel my rage into something constructive that can be shared with others who may (or may not) feel the same way. Since making these hangings, I’ve used them as protest banners that I take to public rallies in Melbourne, Australia, where I live. For example, in March 2015 I used them in a Black Friday rally against the forced closure of rural Aboriginal communities in Western Australia.

While walking in public with these works, I notice that they attract special attention because of their materiality and the obvious amount of time that has gone into making them. People regularly stop me to ask: Did you make these? What do they mean? While some people come up to tell me why they like them, even more share a personal story about their own connections with the practice of craft. On the other hand, when these works were hanging in a community gallery, I observed people being very offended by the use of bad language. Others politely asked around as to what the word “patriarchy” meant. Whatever the response was, these moments where strangers feel compelled to interact and reflect can be understood as points of rupture where a kind of political space is opened up, if only briefly.

For Betsy Greer, writer, maker, and editor of Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism (2014), the very essence of craftivism lies in “creating something that gets people to ask questions; we invite others to join a conversation about the social and political intensions of our creations. Unlike more traditional forms of activism, which can be polarizing, there is a back-and-forth in craftivism … It turns us, as well as our work, into vessels of change” (p. 8).

An important strategy for inciting people to start asking questions through my practice is sewing together different layers of meaning, associations, and cultural references. I do this using not just written language, but also visual cues, metaphors, and symbolism, combining different textures and materials to form an enticing tactile surface. This way, rather than glancing over the written words and responding only to the text, people are enticed to engage with other senses and ways of knowing: they are compelled to touch and feel with their hands, to dwell with their eyes. In this manner, the crafted works trigger memories, emotions, and associations that provide multiple entry points to the work.

This strategy of layering meaning in order to make a political work more intriguing is something I learned from my grandmother, textile artist Dawn Fitzpatrick. Over a period of thirty years, starting in the mid-1970s, Dawn made large-scale figurative textile wall hangings, a practice she referred to as “cloth art.” Her work, which was often political and almost always incorporated symbolism relating to her own faith, combined quilting, patchwork, machine embroidery, appliqué, and drawing and painting techniques.

Dawn Fitzpatrick, The Slide, Ein Karem (1992)

Photo: Tal Fitzpatrick

One of Dawn’s many politically intriguing works is known as The Slide, Ein Karem. This hanging depicts the unique sculptural slides at a playground in Jerusalem, where two Jewish mothers were stabbed to death by an Arab while waiting for their children. This piece was her “soft” response to a situation in which authorities refused to erect a memorial plaque for the murdered women, as “innocence must prevail, not bitter memories” (Fitzpatrick, 2010). Dawn depicts the children on the slides as butterflies, writing: “The butterfly can be a symbol of rebirth, an emblem of the soul fluttering free.” By way of cloth art, she was able to create a different kind of memorial to the memory of this tragedy. This hanging acts as a touchstone, a memory device for sharing a story that was too traumatic and too politically fraught to enshrine into words on a plaque. Yet at the same time, depending on how many of the symbols and clues you can read in the work, the full story it tells is likely to entirely escape you.

Tal Fitzpatrick, Fuck Your Patriarchy (2014),

90cm x 100 cm, machine-quilted wall hanging made

using new and recycled materials and fabric marker.

Photo: Tal Fitzpatrick

Like Dawn, I look to create hangings that patch together different symbols, textures and significance in order to allow audiences to weave their own meaning into the work. In my “Fuck Your Patriarchy” hanging, there are, among other things, biblical symbols—such the apple (core), the snake, and the “unclean” raven, which Noah sent out from the ark, but which never returned—and butterflies. It is here, in this space of ambiguity, confusion, and conflict, that the potency for discussion inspired by the work is found: What does this mean? What is the story behind this work? Why did someone take the time to make it? These are questions that can only be resolved through conversation.

Philosopher and political theorist Jacques Rancière’s (2009) thinking can help us to articulate how such an approach to activism might be effective. According to Rancière, the goal of the activist is to open a space for inquiry where anyone can speak as long as they are aware that whatever they say can and will be questioned and challenged by others. These open spaces for conversation are those where we feel empowered to share our opinion. Rancière describes these temporal spaces as political moments: “A political moment occurs when the temporality of consensus is disrupted. It occurs when a force is capable of exposing the imagination of the relevant community and of contrasting it with a different configuration of the relationship of each individual to everyone else” (p. ix).

However, these political moments, where political debate and what Rancière calls “dissensus” are tolerated, are becoming increasingly hard to come by in societies fixated on consensus. Furthermore, political moments are further delegitimized because they are centered around opinion, and since Plato, “opinion” has largely been understood as the opposite of thought. To reclaim the importance of opinion, Rancière argues:

Opinion is actually the space in which the possibilities of thought and the mode of community these possibilities define are determined. Opinion is not a homogenous space for the lowest form of thought, but rather a space in which to debate what can be thought under particular circumstances and what the consequences of this thought might be. (p. ix)

For craftivists, the implications of this celebration of creativity and individual opinion are that there is great power in creating engaging spaces where a diverse cross-section of people can express their opinions and contribute to a broader debate. As Greer explains, “The creation of things by hand leads to a better understanding of democracy, because it reminds us that we have power” (p. 8). So while some might criticize craftivism for being too “nice” or too gentle, for me, craftivism is effective precisely because it avoids antagonism in its preference for physical and material-based processes for exchanging opinions.

As a craftivist, I’m not so much interested in trying to convince people to think or behave in a specific way. Rather, I’m more concerned with how my material practice can trigger political moments—or spaces where opinions can be expressed, stories told, and dissensus explored. For me, at its core, craftivism is about reclaiming and restoring our own political agency through a process of making opinionated works that encourage people to ask questions and engage with different ideas and with each other. It is an imaginative and creative force capable of bringing about real-world change, however small it may be.

Katve-Kaisa Kontturi knitting with Tjanpi Desert Weavers and working on the Big Knitted Welcome Mat community project. Photos: Katve-Kaisa Kontturi (left) and Kate Just (right)

Crafting Relational Activism | by Katve-Kaisa Kontturi

In this section, I continue to widen the conventional understanding of contemporary craftivism by reflecting on two projects that, in their own ways, made me rethink what can be thought of as activist practice. In July 2015 I took part in a basket-weaving master class run by Tjanpi Desert Weavers at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. TheTjanpi Desert Weavers are a group of Indigenous Australian women from the Central Desert, the so-called Red Center. Like people who are invited to give master classes usually are, these women are masters of a certain technique: basket-weaving. They excel in fiber art.1 They held the class just before the opening of the Tarrawarra Biennial, a contemporary art exhibition organized in cooperation with the prestigious Melbourne Art Fair, in which they were likewise invited to participate alongside major Australian artists. This year, their work was also presented at the Australian Pavilion during the Venice Biennale.

Tjanpi Desert Weavers with their work at the completion of the Tarra Warra Camp. Front left to right:

Niningka Lewis, Yangi Yangi Fox, Roma butler, Molly Miller, Rene Kulitja. Back left to right: Fiona Hall, Mary Pan, Nyanu Watson, Angaliya Nelson. Photo by Jo Foster. 2014. Copyright Tjanpi Desert Weavers, NPY Women’s Council.

When we as art students and teacher-researchers entered the class, we didn’t quite know what to expect. The briefing was very brief indeed: we learned that our teachers were in Melbourne for the first time and that for our teachers, Melbourne felt as outback as their desert was to us. They had travelled thousands of kilometers, and they didn’t speak much English. Also, they had brought all the materials we needed with them: the grass we would use had grown in the red desert ground.

There were no verbal instructions or concrete illustrations of how to proceed and no technologies involved, other than the needles passed to us, and grass and fiber ubiquitously piled around us. I sat next to a teacher called Molly, and without many words, she grabbed some fiber and started a basket by making the first knot. Then she began to integrate the grass by weaving the fiber around it: there was a basket silently in the making.

Fiber art in the making. Photo: Katve-Kaisa Kontturi

To learn how to weave, we couldn’t but follow our teacher’s skillful hands—her body moving with the basket in becoming. Observing Molly and other students around me, I learned a lot. We worked in almost complete silence; we didn’t chat, we didn’t make friends as one often does when crafting together. In fact, I don’t even remember the faces of my fellow crafters very well. Individuals were not really the issue: all we did was to focus on learning to work with the fiber, to feel the fiber, and to add the grass filling to make the basket beautifully round. We learned by making and following each other and our teacher weaving fiber. By doing that, we learned more than just how to make baskets. Working side by side, elbow to elbow, rhythmically repeating the phases of basket-making, we wove not only certain fiber objects, but each other, closer together.

Of course, inequalities dividing Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians could not possibly be overcome during one or two master classes. But still, something happened: the sensation of possibility through collaboration was felt as our bodies worked closely together, learning from each other. This is what I would call a subtle sort of relational activism, one based not on grand gestures or loud demands, but on bodily relatedness (Manning, 2009; Massumi, 2011) and hence on the increasing feeling of communality.

Some weeks after participating in the Tjanpi Desert Weavers’ master class, I participated in another community-based craft project led by Kate Just, a US-born contemporary artist living in Melbourne, who specializes in knitted sculptures. The project took place in and was funded by the City of Greater Dandenong, which, since 2002, has been one of Australia’s official “refugee welcome zones.” The aim of this public project was to bring together local people of multiple ethnic backgrounds by collaboratively producing a Big Knitted Welcome Mat (the title of the project).

Knitting the big welcome mat. Photo: Kate Just

I joined the project when it had already begun, so I benefitted from being surrounded by people who already knew what they were doing. I hadn’t knitted for years, and my sole language of knitting was Finnish. Therefore, I struggled a bit to get going and became all the more confused when I realized that knitting terms also differed according to American and Australian/British conventions. But soon the confusion transformed into an invigorating discussion of how “knit” and “purl” were expressed in different languages, and when and how it was that we had learned to knit—whether the process took place in Australia, Chile, Finland, Malta, Italy, Singapore, Russia, or China. Side by side and each in their particular way, we knitted together, and also learned from each other. But this time, we were not silent. As we sat and knitted, we chatted about our everyday practices and differences in our lives. The giant doormat, with its more than 100 squares of multiple textures and different stitches, bore witness to this process of discovering our differences.

A close-up of the welcome mat. Photo: Kate Just

When I thought about how the mat had come to embody diversity, difference, and close connection, I remembered how we had received clear instructions of what to do. Indeed, in comparison to the Tjanpi Desert Weavers’ master class, we were provided with a detailed how-to: the red squares were supposed to be 20 x 20 cm in size, and 104 of them were needed to construct the mat. Although there were clear rules, I didn’t feel restricted. Later, I understood that knitting instructions worked as “enabling constraints.” In Erin Manning (2013) and Brian Massumi’s (2010) relational philosophy, “enabling constraint” means something that triggers action and does not restrict creativity, but rather, encourages it within certain limits.

It was through these enabling constraints that our knitting project brought together bodies of women of different ages and of multiple ethnic and social backgrounds in a way that wouldn’t have been otherwise possible. It was when we were putting the mat together and attaching the letters to form the word “welcome” that we worked closest together. We had to climb to the table, stretch our arms, and twist our necks. Without the project, and its material restrictions, we would never have worked in such close bodily proximity. That is, we wouldn’t have learned to relate our bodies to each other in such an intimate manner while remaining relative strangers to each other. This comes close to Joanne Turney’s (2009) claim in The Culture of Knitting that “knitting is a great leveler: the one activity or practice that can bring people together and overcome difference, creating harmonious environments in which sociability is at the forefront” (p. 144).

Working in close proximity. Photo: Kate Just

Although I share Turney’s genuinely affirmative understanding of what communal crafting can do, there are significant differences in our thinking. I would not claim that crafting can overcome differences or create harmony. Rather, if a greater extent of communality is achieved, it is because people have learned to open their individual bodies and to feel how their relation to other bodies is both constitutive and indispensable. This does not erase differences, but rather, teaches us how we can cope with them, relate to them, live with them towards the future. This is how craftivism as relational activism works.

Brief Moments, Slow Processes, Subtle Relations: Craftivism as Micropolitics

In this essay, we have provided a glimpse into some of the diverse forms of craft-based activism currently being practiced in Australia. As practitioners and participants, we have taken part in rallies, created visually complex wall hangings, and attended a basket-weaving master class and a community knitting project. While the adversarial style of criticism typical of many “rad crafters” is not present in the projects we have introduced, we nevertheless understand them as craftivist practices. The reason for this is that they all create space and possibilities for change, and therefore for the imagining and making of a better world, by means of crafting.

From Knit Your Revolt’s media-attracting activism that bursts with witty slogans highlighted by bright colours to the quiet process of being taught to weave baskets by the Tjanpi Desert Weavers, what brings the projects together is their ability to open up political moments. Whereas for Rancière, political moments are first and foremost temporal spaces for opinions to be expressed and debates provoked, we want to emphasize that the material-physical practice and tactile materials of craft-making are indispensable for these moments to occur. However, as we have described, in crafting and thinking with craft objects, we are dealing with a very specific kind of materiality: a materiality that is felt as it triggers memories and opinions as bodies open up for collaboration, and as sensations of possibility for mutual futures arise between bodies closely relating to one other.

In our understanding, the repetitive, rhythmic, and time-consuming movement indispensable for crafting—whether communal or individual, or involving machine-sewing, embroidery, basket-making, crocheting, or knitting—is not only thoroughly material, but relational. This sort of conception of materiality as (micro)movement is characteristic of new materialist thinking. Instead of grand-scale and calculable transformations in society, new materialism looks for tiny or almost imperceptible actions, and believes in their potential to produce change (van Dolphijn & van der Tuin, 2013; Kontturi, 2014). This focus and belief in the transformative power of brief political moments, slow repetitive processes, and subtle yet sensible relations is called micropolitics.

What we want to suggest is that craftivism as micropolitics is as political as any macro political action such as large-scale demonstrations or the implementation of a new law. Its political efficacy lies in its ability to engage with diverse groups of people and provide them with a sustainable way of interacting, communicating, and taking action with one another.

Tal Fitzpatrick is a Melbourne-based textile artist, craftivist, and community development worker who is currently completing a PhD with the Centre for Cultural Partnerships at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. Having taken up her paternal grandmothers’ figurative approach to appliqué quilting Tal’s practice-led research explores the intersections between socially engaged art, activism and feminist and new materialist approaches to craft. For more information on Tal’s latest projects, please visit: www.praxialpractice.wordpress.com

Katve-Kaisa Kontturi works as a postdoctoral fellow in the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne. She is a founding member of the European New Materialist Network, and has devoted her academic career to the study of relational materialities of art and the body. Kaisa enjoys curating affective exhibitions, the bodily rhythm of crafting, and dressing in beautifully patterned vintage frocks.

1. In addition to painting, fiber art is one of major sources of income for Indigenous Australian communities, which is, understandably, a controversial issue in itself; they have no choice but to produce art that sells well, that looks Aboriginal enough and is of economic value on the art market. However, Tjanpi Desert Weavers art is said to be truly innovative, therefore exceeding any presumptions of what their art should look like. See Tiriki Onus and Eugenia Flynn and Diane Moon. ↩

References

Blanket Lovez. (2015). Blanket Lovez. Retrieved from www.blanktlovez.com.

Corbett, Sarah. (2014). Interview with Sarah Corbett of the Craftivist Collective. In Greer, Betty (Ed.) Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism (pp. 203-212). Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Fitzpatrick, Dawn & McGorman, Lee. (1975). Cloth Art [24 slides] Sydney: Crafts Council of Australia.

Fitzpatrick, Dawn. (2010). Inside the gates of Jerusalem. Unpublished Manuscript. Tal Fitzpatrick’s personal archives.

Greer, Betty. (2014). Knitting craftivism: From my sofa to yours. In Greer, Betty (Ed). Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism (pp. 24-36). Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Hamilton, Inga. (2014). Daily narratives and enduring images: The love encased by craft. In Greer, Betty (Ed.) Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism (pp. 24-36). Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Inspiration Quilts. (2014). Inspiration quilts. Retrieved from www.inspirationalquilts.com.au/donations.html

Just, Kate. (2014). Just’s Hope and Safe project. Retrieved from http://www.katejust.com/hope-safe

Knit One Give One. (n.d.). Knit one give one. Retrieved from www.knitonegiveone.org

Knitting for Brisbane’s Needy. (n.d.). Knitting for Brisbane’s needy. Retrieved from www.knittingforbrisbanesneedy.com.au

Kontturi, Katve-Kaisa. (2014). Moving matters of contemporary art: Three new materialist propositions. AM: Journal of Art and Media Studies. 5.

Manning, Erin. (2009). Relationscapes: Movement, art, philosophy. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Manning, Erin. (2013). Always more than one. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Manning, Erin & Massumi, Brian. (2014). Thought in the act: Passages in the ecology of experience. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Massumi, Brian. (2010). On critique. Inflexions 4 Retrieved from www.inflexions.org/n4_t_massumihtml.html.

Massumi, Brian. (2011). Semblance and event: Activist philosophy and the occurrent arts. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Moon, Diane. (2009). Floating life: Contemporary Aboriginal fibre art. South Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery.

Moore, Mandy & Prain, Leanne. (2009). Yarn bombing: The art of crochet and knit graffiti. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Onus, Tiriki & Flynn, Eugenia. (2014, Aug 13). The Tjanpi desert weavers show us that traditional craft is art. The Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/the-tjanpi-desert-weavers-show-us-that-traditional-craft-is-art-30243

Park, Andy. (2013 Nov 18). Clicktivism: Why social media is not good for charity. The Feed, SBS online.

Parker, Rozsika. (2010). Subversive stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine. London: I. B. Tauris.

Perry, Gillian. (1999). Gender and art: Art and its histories series. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Quilts for Kids. (2015). Quilts for kids. Retrieved from http:www.quiltsforkids.org/volunteer/

Rancière, Jacques. (2009). Moments Politiques: Interventions 1977–2009. New York: Seven Stories Press.

SBS (2015, March 6). Female protesters dressed as men try to crash LNP event. SBS Online. Retrieved from www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2015/03/06/female-protesters-dressed-men-try-crash-lnp-event.

Scarves with a Purpose. (n.d.). Scarves with a purpose. Retrieved from www.scarveswithapurpose.com

Sole, Ocean. (2015). Cleaning beaches, creating masterpieces. Ocean Sole. Retrieved from www.ocean-sole.com.

Tarrawarra Biennial 2014: Whisper in My Mask. Tarrawarra Museum of Art. Retrieved from ww.twma.com.au/exhibition/tarrawarra-biennial-2014-whisper-in-my-mask/

Turney, Joanne. (2009). The culture of knitting. New York: Berg Publishers.

van Dolphijn, Rick & van der Tuin, Iris. (2009). New materialism: Interviews & cartographies. Open Humanities Press.

Victorian Quilters Inc. Australia. (n.d.) Victorian Quilters, Inc. Australia. Retrieved from www.victorianquilters.org.