Undo It Yourself: Challenging Normalizing Discourses of Pinterest? Nailed it!

Morgan C. Leckie

This project explores the resistant rhetorics of online environments through site discourse analysis and person-based research of participants on popular social media scrapbooking and crafting website Pinterest.

They tell us from the time we’re young

To hide the things that we don't like about ourselves

Inside ourselves

I know I'm not the only one who spent so long attempting to be someone else

Well, I’m over it

– Mary Lambert, Secrets

Entering the Pinterest Conversation

“I sent you some pins for the wedding,” my older sister announces over the phone late on a Wednesday evening. “Are you still looking at Pinterest for research?”

“Yeah… I think I could spend a lifetime looking at Pinterest. I don’t know why, but I can’t let it go…” I trail off and reassure her I will check out the maid of honor dress ideas and DIY centerpieces when I get home and hit end call in a rush because, as usual and like most working single moms, I am in the middle of something else. That something: driving my seven-year-old daughter across State Route 101 into Indiana for her weekly guitar lesson. She is singing Mary Lambert at middle volume and kicking the passenger seat, of course. And as she sings I mull over the lyrics: They do tell us from the time we’re young to hide things… and they—that nebulous collective heteropatriarchal someone?—also tell us as women and girls what we ought not to like about ourselves, what we ought to hide.

For Pinterest users, 85% of whom are women (Smith), what we “ought to hide” often includes our failed attempts at perfection—our sagging pineapple upside-down cakes, un-toned arms, and, as Lindsey Harding notes, children’s birthday parties with which we are forever “disappointed.” But who defines this “perfection” on Pinterest and within the larger context of our culture matters, and very often what the social media site asks us to hide, what it hides itself, are the class, race, sexuality, and gender identities—the lived and embodied experiences—that fall outside the default Pinterest search results.

One has only to read through recent Harlot issues to see evidence that legitimates my musings. Lindsey Harding reflects on her own experience of Pinterest to reject the “box” the site reinforces for mothers, arguing that “Pinterest captures the attention of mothers through the curation and appropriation of domestic content means that the site does more than captivate mothers; it contains them, locking them into a series of behaviors and a single maternal identity: mother as domestic housewife.” Writer Matthew A. Vetter aims at queering the site in order to “to critique social networks by calling attention to their implicit ideologies,” arguing that his project is “a disruption of consumer referrals via displacement of normative gender production.”

These conversations are not contained to Harlot: Katherine DeLuca says Pinterest users “engage in rhetorical community shaping, challenging the dominant narratives that shape the online space they inhabit.” DeLuca, Harding, and Vetter—along with bloggers Amy O’Dell, Amelia McDonall-Parry, Bonnie Stewart, and Rob Horning—are interested in thinking about the site in order to challenge, disrupt, and yes, reject the lies it perpetuates about gendered experiences of consumption, craft, and composing the self online.

It seems that many writers recognize what I have spent over two years trying to understand: the paradox of Pinterest. In one sense, it is a much-needed safe space for women on the internet, a place—unlike say, Reddit or Wikipedia—where to claim a female body does not mean risk of trolling rape threats and systemic silencing (Gruwell). But Pinterest is also a mechanism—one that polices and normalizes—that yes, “contains” and “produces” reductive notions of our lived experiences as women.

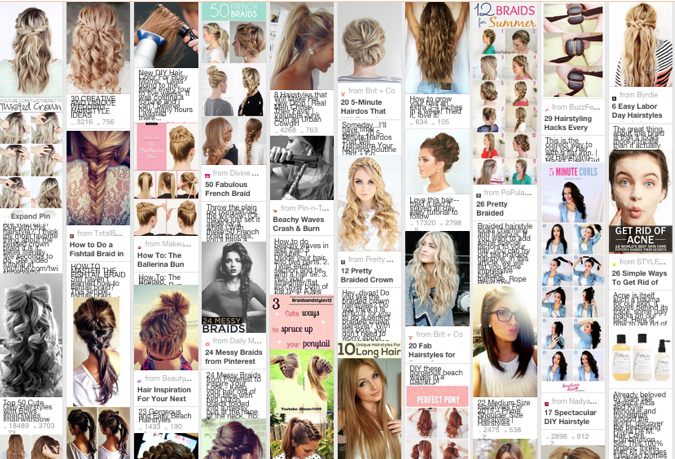

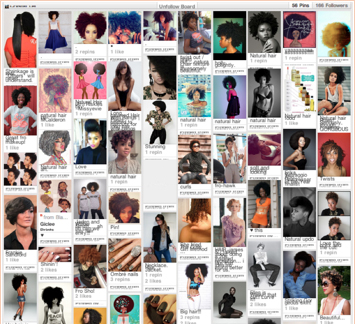

Don’t believe Vetter, and Harding, and me? Hop on Pinterest right now and search for “hairstyles.” This is what you will find:

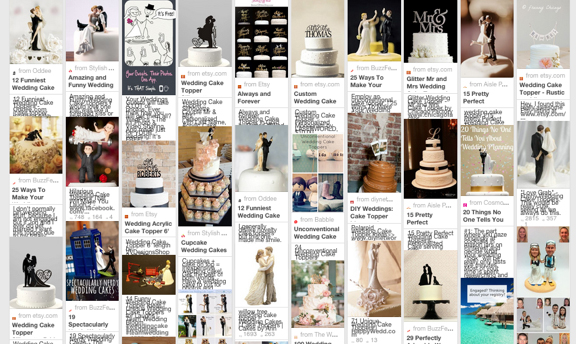

Now try searching for “wedding cake toppers” or “spring fashion ideas.” Go ahead, I’ll wait. Let me guess, your results look something like this:

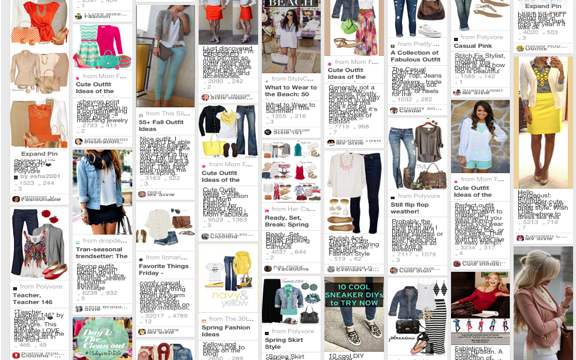

Or this:

And perhaps now you are asking, Do only white women have hair to style? Are white heterosexual couples the only people who get married? Must I be a size 0-2 white woman with unlimited access to money in order to wear fashionable Spring ensembles? Of course, the very real answer to these questions is No.

And if, like most Pinterest users, you do not see the “social and political contradictions” of your own real body and life and finances reflected across the ocean of images that blanket your screen after you perform such a search of pins, you understand exactly what the site is asking you to keep secret, to consider outside the default. That is your curly hair, your dark skin, your cellulite, your low income, your queer sexuality, your mature age—the “imperfections” or failures at idealized womanhood, motherhood, partnership that, let’s face it, all of us experience in one way or another. It is absolutely unsurprising then that nearly all 15 of the female Pinterest users I surveyed and interviewed in my long year of person-based study of the site noted frustration with these (as Vetter calls them) “implicit ideologies.”

That’s right: ask women using Pinterest to reflect on the site, and you will, I promise, begin to understand (as I have) that the larger cultural and scholarly projects of feminism and queer critique are not only for academics and are not at odds with the knowledge making that happens on Pinterest. Here I share the practices and observations of a handful of Pinterest users, my own and those that were so generously shared with me in order to make the case that sites like this one—for all its oppressive and restrictive programming—are not outsmarting the real women who shape and change and undo them.

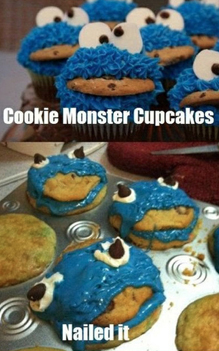

The real DIY project of Pinterest is not to emulate or aim for perfection—but to think instead about how that “perfection” invites challenge. As one astute study participant notes, “I actually really like the ‘Pinterest fail’ culture that has emerged that emphasizes that it’s ok to try these ideas, fail, and then laugh about it. I think we could use more of that honesty on the site.” More honesty and more laughter—that’s what my research helped me uncover.

Check out this Pinterest fail (figure left). Are you laughing? Because those cupcakes are hilarious—both the impossibly “perfect” Pinterest original and the hot-mess, honest result overlaid with the obviously ironic “Nailed it.” This trend to tell the truth is a refusal to “hide the things that we don’t like about ourselves,” and the humor it uncovers is a refusal to “not like” those things in the first place.

Hold on to this Cookie Monster cupcake image as you continue to read. In so many ways it works as the perfect epigraph for and instance of the smart, empowering, queer resistance against normalizing discourses on Pinterest that I learned about through my research of pinboards and users. This project, which I find so much joy in detailing and discussing here, helps us see that we—women, Pinterest users, writers, and bloggers interrogating dominant discourses—are “not only one[s] who spent so long attempting to be someone else,” and we are certainly not the only ones who are “over it.”

Why and How I Came to a Qualitative Study of Pinterest

I love talking about myself. Really—ask me anything. But that’s not why I’m about to tell you the very self-reflective story of why and how I began studying Pinterest. I’m talking about myself “strictly,” in the words of Harry Potter’s Professor Slughorn, “for academic purposes, of course.” You see, feminist social science researchers have made and tested the claim that ethical feminist research cannot pretend to be objective (Haraway 1988, Harding 1987, Hill Collins 1990), and many composition scholars agree that our own subject positions as researchers, as well as our experiences as women, are important factors that must be considered in the knowledge we produce (Kirsch 1995, 1999, Ritchie 1995, Royster 1996, Sullivan 1992, Jarratt 1998).

In my imagination these feminist thinkers are secretly members of a badass motorcycle mafia—one that will fly down a two-lane highway to my front door if I forget that “it is a delusion… to think that human thought could completely erase the fingerprints that reveal its production process” (Sandra Harding 57). Therefore I should tell you a bit about my position as a researcher, because these scholars are right: my particular standpoint—that is, who I am and how I approached Pinterest when I initially signed up as a user—are the “fingerprints” of the “truths” I see within the site, the study of it, and the participants who shared their ideas and pinboards.

And so in the interest of responsible feminist research and putting my money where my Mary Lambert epigraph is, it’s confession time: I hide a lot of secrets. Not very well, given my visible and visibly poor white trash tattoos, mind you—but I try. Because unlike the “traditional” or “ideal” PhD candidates I meet, I came to academe pretty rough around the edges. I worked as a food and cocktail server, childcare worker, and hairdresser for the ten long years it took me to finish my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. I’ve never been to Europe. I don’t even have a passport. I do, however, have a seven-year-old child whose father I never married and mountains of student loan debt. I’m the first of my immediate family to finish a graduate degree, the second to complete college.

In so many instances, I have closeted these very working class experiences of my past. In doing so, I have been “attempting to be someone else”—the perfect middle class academic, I suppose. Think back to that Cookie Monster cupcake meme; in my own life those perfect cupcakes with their bright eyes and uniform smiles are the “perfect PhD scholars”—twenty-something white women with pearl earrings, accomplished fiancés, parents who send money, and ten-year plans to make tenure and rule the field. I am the hilarious, lopsided reality—all runny icing and unpaid bills. Perfect academic woman? Nailed it!

This confession of my working class identity and my anxious attempts to affect middle class cultural norms helps makes clear why I initially felt disinclined to use Pinterest. In 2012, when so many of my “respectable college friends” urged me to join the site, I bristled a bit. I did not feel that I belonged there. Pinterest seemed unappealing to a woman like me: I was not crafting jewelry to sell on Etsy or sewing a burlap diaper bag to give to a friend; I was not planning a wedding or special, heart-shaped, and nutritious meals for my children. As a single working mother, trying to claw my way into the middle class by way of graduate scholarship, simply feeding myself and my child is a victory. I saw perfection on the site—and I have yet to attain anything that comes close to perfection. Ever.

But then I began to find compelling comments from friends and acquaintances on my Facebook newsfeed. “Pinterest and I have a love/hate relationship. Somedays I love the inspiration. Other days I feel like a total mom failure,” wrote a Facebook friend, Reina,1 in a casual status update. She asked friends if she was “the only one” who feels this way and received a number of responses voicing similar disempowering feelings. “No! It’s overwhelming and unrealistic,” “Nobody’s house looks like any of that stuff,” and “I know a lot of people who feel fat and poor when they’re on there [Pinterest],” are examples of the comment feedback to Reina’s post that initially piqued my curiosity and commitment to participating in Pinterest. I realized that I was not alone in the anxiety I felt when I tried to join the site. I wanted to know how and why Pinterest made some women who used the interface feel so negative.

In response, I created a user account on Pinterest in the spring of 2013. Mostly because Jen Almjeld and Kristine Blair call for “establishing a technofeminist research identity” that participates in using as well as theorizing the technologies we examine (103). They urge the digital feminist researcher to approach the site of her inquiry as a user in order to “bridge the gap between researcher and participants” (103).

Step one: sign up for Pinterest and use the interface. I noticed right away that this new digital DIY space enabled me to be “just another middle class white woman” who could fantasize about the economic and cultural capital—the power, essentially—I might one day embody. I could, in some small way, imagine myself one day fitting in at the graduate department parties, the definitions of “good mom” and “perfect academic woman.” It was fun.

Playing on Pinterest was less about the crafts I would do with my daughter or the ways I might repurpose the tables and bureaus undergraduates toss out each spring—I would do those projects, sure. But the greatest, most important, and most insidious project I found on the site was the project of refinishing the self, sanding and painting and polishing the woman I am—the crooked Cookie Monster always outside some better, cleaner person’s door—into the middle class woman I thought for so long that I was supposed to become.

This class anxiety caught me off guard. And it made me look for ways to understand how the act of appropriation and aspiration might be empowering, not simply an act of reinforcing and stabilizing the kind of social “boxes” from which I had been trying my whole life to escape. Appropriating and circulating—“re-pinning” as it is called—is the visual and textual images of other users is essentially the sharing of reality. For comp/rhet scholar and potential motorcycle mafia member, Kristie S. Fleckenstein, “Appropriation is the process by which a community takes as its own perception, articulation, or shared vision, making it a part of its taken-for-granted reality, its construction of the real” (8). She complicates this by considering the notion of community when she claims that any “construction of the real (including “the reality of the body”) gains validity only when it is shared” (8).

So, as I shared and circulated and appropriated within the middle-class-white-lady landscape that is Pinterest, I began to realize that I was reinforcing the oppressive class boxes I wanted to transcend, change, obliterate. I was, after all, willingly sharing the vision of “perfection” and helping to construct the reality that these dominant definitions of womanhood, of craft, of class matter in our material lives. In wanting and gathering and sharing the false notion that there is only a white middle class definition of what happiness and success and beauty looks like, I was doing my part in making that falsehood seem true.

But before you run to your own Pinterest page and rethink every pinboard you’ve ever constructed, keep calm and pin on, reader—because appropriation and articulation that occur on Pinterest often challenge “visible cultural beliefs about the places and representations of class, gender, ethnicity, and other identities and embodiments” (Wysocki 37). And those moments of challenge are what kept me pinning and reading and thinking. If Kirsch and Ritchie have taught me anything, it’s that “claiming our experience” as feminist researchers “may be as inadequate for making claims to knowledge as traditional claims from objectivity are” (10). My own experience of and perspective on Pinterest was not enough; listening to other women—with their varied positions and perspectives—helped me understand the site through the knowledge we produced after the IRB application was approved and the survey and essay responses rolled in.2

In the sections that follow, I will share a few of the participant experiences and pinboards I found inspiring. They tell stories that, like my own, support the position I argue here about Pinterest and Web 2.0 more broadly: that is a landscape that often regulates and restricts, digitally reconstructing dominant discourses and identities. But those regulating representations are only waiting to be challenged, changed, undone by each of us. Pinterest, like so many other feminized social spaces on the Web, offers users the chance to tell our truths against even the most dominant discourses.

Participant and Site Data: Pinning Challenge and Change

Carla: Undoing Assumed Whiteness

Carla3 uses Pinterest like most of us do—to imagine her possibilities. Like many other users, her boards include pins of workout routines, recipes for family dinners, and interior decorating ideas. And yet, she is what I would call and “oppositional user” of Pinterest. Carla describes herself as “an African American woman, 29, married with no children” and notes that the one thing she would change about Pinterest is the lack of “African American posts on black hair and fashion of the black community.” While looking for images of hairstyles to take to her stylist, Carla noticed the same phenomenon that plagued my own searches for pins. She searched “hairstyles” only to find pages of pins featuring almost exclusively white women. Carla added the modifiers, “black” and “ethnic” in order to find hairstyle ideas for her “type” of hair.

In response to this discovery, she constructed the above pinboard and tagged it as simply “hairstyles” to deliberately resist the Pinterest assumption that black, natural hair belongs in a separate or marginalized search. She pinned original photos—what is called “user generated content”—of her own hair and body. In this way, Carla demonstrates how visual, embodied rhetoric can produce and appropriate in order to resist and “un-do” practices that normalize certain and dominant representations and values. Carla is noticing, as I have, that the Pinterest user is assumed, and that assumption includes whiteness. More importantly, all that the “right” kind of whiteness implies about body type and income level is reflected and repeated across thousands of pins.

Ruby: Undoing Normalized Thinness

It is this repetition of limited representation that leads participant Ruby, a self-described “full-figured” and “working poor” woman who works outside the home but is the primary caregiver to her three small children, to express anxiety about the possibility she can imagine and look at on Pinterest. In order to find women who look like her, who wear clothes that she can fit and afford, she must attach modifying search terms to “fashion”—terms like, “plus size” and “inexpensive”.

This is how Pinterest polices user self-perception; we enter the site as embodied women, but must disembody—must use language and text to find ourselves, piece ourselves together—within the nexus of visual and consumable data. When those of us whose needs and bodies are not immediately and readily available as means to construct and communicate our reality, we must look for it by identifying ourselves against dominant and idealized womanhood.

Considering the negative cultural implications of such words as “inexpensive,” “non-white,” and “plus size” is crucial for understanding any feminist critique of Pinterest. The search terms to find the margins of Pinterest remind a user like Carla or Ruby that she is “not normal”; she is “a different kind of” woman than the majority of pinners with whom she connects through the site. But it is too simple and too, yes, “cursory” to paint Pinterest as an environment of anti-feminist and oppressive constructions. After all, Ruby notices and critiques and ultimately rejects the Pinterest notion that her body and class subject positions are something she needs or wants to hide. The study survey gave Ruby the opportunity to express how “over it” she is while she pins and explain that she now primarily uses the site to search for recipe ideas.

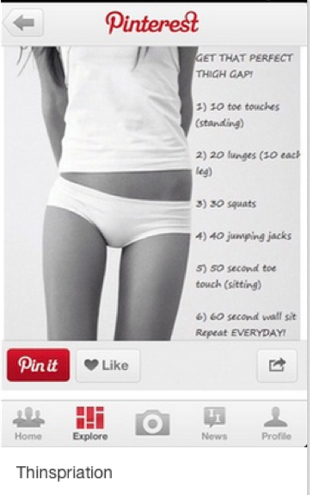

Ruby is not alone; nearly every research participant listed “Thinspiration Boards” (or “bullshit,” as one user called them) as among the most-irksome content on Pinterest. Typing the term “thinspiration” into Pinterest’s search bar yielded hundreds of boards and countless individual pins—many user-generated and many re-pinned from other internet sources such as Tumblr and Facebook. These pinboards are dedicated to inspiring users to lose weight or stay “skinny,” and their message (seen in the example shown above), as in all thinspiration textual/visual pins, is clear: perfection is thinness; idealized thinness is possible through hard work and restraint; and the idealized thin body is usually, in fact it is almost always, white. For Ruby and for so many of the women who shared their perspectives, thinspiration discourses are like so many of the DIY projects posted on the site; they are an idealized standard to interrogate, to fail at, to laugh about.

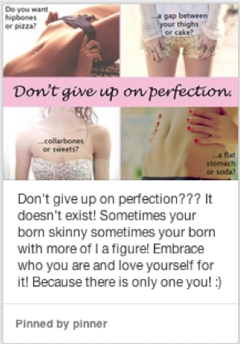

They also exist as an opportunity to resist and challenge normative ideas about femininity many users. On countless pinboards across the site, I discovered user-generated content that appropriates thinspiration pins to add commentary—to talk back to the “bullshit” of body shaming. The example in the figure to the left demonstrates one user’s intervention into—and literally over—popular thinspiration messages. This pinner has added text to a thinspiration pin inviting her fellow Pinterest users to question the notion that “hard work” and diet can lead to “perfect” embodiment. She rejects the concept of “perfection” and dismisses it in her construction and communication of reality, encouraging others participating and existing within the site to do the same.

Emma: Undoing Heteronormativity

Another example of a pinner rejecting the hegemonic messages the site promotes is Emma. She reveals the heteronormativity of the site and arrives at the conclusion that there are ways that she can change and challenge the aspects of Pinterest that marginalize and exclude her lived experience as a “lesbian woman.” Emma notes that she loves Pinterest for how the site helps inspire her ideas for her upcoming wedding. But she resents that she has “to make detailed/specific searches when planning [her] wedding, since [she is] in a same-sex relationship. For instance, [she] can’t just search ‘cake toppers’ [she has] to search ‘same-sex’ or ‘lesbian’ cake toppers.” Emma also complains that she “CANNOT find ideas for a wedding day outfit for [her] fiancee” who does not fit gendered assumptions about the site’s female users (Emma, survey short answers).

Emma laments these limitations of Pinterest, because she earnestly likes the site so much, calling it “visual” and “fun.” Like Carla and Ruby, Emma understands her own wedding and relationship with her partner as somehow on the margins of womanhood. She cannot “find” herself within the boards and pins through which she scrolls. But also like so many of the participants and pinners I observed, Emma refuses and rejects the notion that the reality reflected on Pinterest is unchangeable:

Obviously I’d like more lesbian couples that reflect my life—and to not have to specifically search for it. If I search “wedding” I should see ALL couples, not just straight couples. Straight people don’t have to search “straight” or “hetero” wedding after all. And not all lesbian couples are femmy dress wearing types… But this makes me think, if I can't find couples like me on Pinterest, I should/could search the Internet for those things and then create my own pins, right? I’ll get on that! (Emma, survey short answers)

Here Emma’s commentary notes an invisible mechanism of exclusion in the web environment of Pinterest and yet expresses why that environment cannot be read as wholly oppressive.  After all, Pinterest is part of “the Internet”—the networked and nearly infinite knowledge production project of Web 2.0 that can offer Emma resources to appropriate and challenge heteronormativity within the pinboards and pins she surfs.

After all, Pinterest is part of “the Internet”—the networked and nearly infinite knowledge production project of Web 2.0 that can offer Emma resources to appropriate and challenge heteronormativity within the pinboards and pins she surfs.

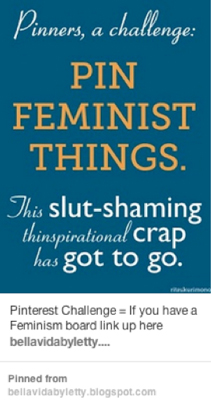

When Pinterest users like Emma, Ruby, Carla, and others notice and challenge the politically-loaded representations of “perfection” within the site, they are participating in activist and intervening rhetoric. And they are not alone. Take a look at two of the numerous examples of subversive pins I found while researching (left and below). These pins were generated and re-pinned by self-proclaimed “feminist” users. Dozens of pins like these help to trouble and question normalizing discourses of Pinterest and call users with resistant agendas to communicate and connect by circulating pins that ask women to “link up” and pin positive and empowering messages.

This can be understood as a resistant movement from within a heteropatriarchal and consumerist digital environment, meant to perpetuate and quite literally promote white, Western, middle class value systems. Pinners who reject the perfection, who laugh at the site’s often invisible hegemonic messages, work to reveal and undo-them for other users.

Final Thoughts: Keep Hopeful and Pin On

When I think about why I am, yes, still and perhaps forever, “looking at Pinterest for research,” I am brought back always to the small girl, the future woman singing unapologetically in the back seat of my car. At this point, my seven-year-old daughter is not at all afraid to reject the things she has been told by our culture to “not like” about her body, her mixed-racial identity, her working class roots, or her emerging sexuality. Examining and understanding how digital cultures work and can be worked against to make feminist and empowering knowledge of the self and others can help the larger project of building a sense of agency, strength, and truth-telling in all “future women.”

After all, as our lived experiences and bodies are increasingly mediated in digital spaces and for “public” consumption and circulation, we are charged with the important work of mediating ourselves—advocating for the kind of public to which we want to belong. And as cyberfeminist scholars like Yvonne Volkart claim, “new technologies and their hybrid outcome are the privileged places of power and resistance today” and that even in the face of “cyborg” or technologically-mediated communication of self—“body, gender, technology, and the fantasies about them are the most important zones where cultural, symbolic and real power take place” (115). Dismissing female-dominated sites like Pinterest as “banal” or “bullshit” or “anti-feminist,” or even simply without invisible mechanics of oppression, takes a far too cursory look at the potential they offer to teach us a thing or two about how “cultural, symbolic, and real power” work, Web 2.0 style.

For me, and for the women who both participated in my study and posted resistant content on the site, Pinterest asks us to keep secrets, sure—but it also invites to truth-tell. Many of us both aspire to be better women, and to participate in what counts as “better” or “perfect” within and against the boards and pins and practices of digital knowledge construction. A project like this research, like the larger DIY project of constructing and remaking or even remaining oneself, particularly in the face of exclusionary discourses—is never really over.

So I encourage you, pin your truth and your secrets; I guarantee you are “not the only one” who cannot make perfect Cookie Monster cupcakes or afford couture-inspired couch covers. Moving our real, messy, queer, ethnic, working class lives from the margins and to the pinboards that reflect the realities to which we aspire as women? Let’s nail it.

Notes

- Facebook user cited with fictionalized name to protect user privacy.

- This project was deemed IRB exempt. Participants were recruited and surveys and consent forms were circulated via Facebook in March of 2014.

- All participant names have been fictionalized for this project to protect user privacy.

Morgan C. Leckie is a Ph.D. candidate in Composition and Rhetoric at Miami University of Ohio, where she teaches courses in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Professional Writing. Her current dissertation research examines rhetorical resilience in reproductive justice and fertility discourses, both historically and in online digital spaces. When she is not researching and teaching feminist rhetorics, she is engaging in the lived feminism of raising her daughter and advocating for women’s access to birth control, abortion, health care and sexual assault recovery and prevention.

References

Almjeld, Jen and Kristine Blair. “Multimodal Methods for Multimodal Literacies: Establishing a Technofeminist Research Identity.” Composing (media) = Composing(embodiment). Eds. Kristin L. Arola and Anne Francis Wysocki. Logan, UT: Utah University Press. 2012. 97-109.

Deluca, Kathrine. “Can we block these political thingys? I just want to get f*cking recipes:' Women, Rhetoric, and Politics on Pinterest.” Kairos 19.3. 2015.

Fleckenstein, Kristie. “Testifying: Seeing and Saying in World Making”. Ways of Seeing, Ways of Speaking: The Integration of Rhetoric and Vision in Constructing the Real

. Eds. Kristie S. Fleckenstein, Sue Hum, and Linda T. Calendrillo. West Lafayette, Indiana: Parlor Press, 2007. 3-30.Gruwell, Leigh. “Wikipedia's Politics of Exclusion: Gender, Epistemology, and Feminist Rhetorical (In)action.” Computers and Composition 37. 2015.

Harding, Lindsey. “Super Mom in a Box.” Harlot. No. 12. 2014.

Harding, Sandra. “Rethinking Standpoint Epistemology: What is ‘Strong Objectivity’?” Feminist Epistemologies. Eds. Linda Alcoff and Elizabeth Potter. New York: Routledge, 1993. 49-82.

Horning, Rob. “Pinterest and the Acquisitive Gaze.” The New Inquiry. 2012.

Lambert, Mary. “Secrets." Heart on My Sleeve. Capitol Records. 2014.

Kirsch, Gesa and Joy S. Ritchie. “Beyond the Personal: Theorizing a Politics of Location in Composition Research.” College Composition and Communication 46. 1995. 7-29

McDonald-Perry, Amelia. “Oh Please, Pinterest Isn’t Killing Feminism,” The Frisky. 2012.

O’Dell, Amy. “How Pinterest is Killing Feminism,” Buzzfeed. 2012.

Smith, Craig. “By the Numbers: 90+ Amazing Pinterest Statistics.” Digital Marketing Resources. 2015.

Stewart, Bonnie. “Pinterest: Digital Identity, Stepford Wives Edition.” The Theory Blog. 2012.

Vetter, Matthew A. “Queer-the-Tech: Genderfucking and Anti-Consumer Activism in Social Media.” Harlot. No 11. 2014.

Volkart, Yvonne. “The Cyberfeminist Fantasy of the Pleasure of the Cyborg.” Cyberfeminism. Next Protocols. Eds, Claudia Reiche and Verena Kuni. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia. 2004. 97-118.

Wysocki, Anne Frances. “Drawn Together: Possibilities for Bodies in Words and Pictures”. Composing (media) =Composing(embodiment). Eds. Kristin L. Arola and Anne Francis Wysocki. Logan, UT: Utah University Press. 2012. 26-42.

Images Used

Screencapture of “hairstyles” search results, Pinterest. May, 2014.

Screencapture of “wedding cake toppers” search results, Pinterest. May 2014.

Screencapture of “spring fashion ideas” search results, Pinterest. May 2014.

lovelyish. "Cookie Monster Cupcakes? Nailed it." Photograph. “The 34 most hilarious Pinterest fails ever. These people totally nailed it!” Justsomething. nd. Web. 12 March. 2015.

Screencapture of participant Carla’s “Hair Ideas” pinboard, Pinterest. May 2014.

Screencapture of “fashion” search results, Pinterest. May, 2014.

Screencapture of “thinspiration” search result, Pinterest. May, 2014.

Screencapture of “thinspiration” search result, Pinterest. May, 2014.

“Pinterest Critique E Card.” Sociological Images Pinboard. Pinterest. May, 2014.

bellavidabyletty. “Pin Feminist Things.” Feminist Pins Pinboard. Pinterest. May, 2014.