“All the Lovely Ladies” and “Celestarium”

Danika Paige Myers

These poems are part of a larger manuscript that explores the poet’s lifelong engagement with knitting and sewing—and with the usually woman-centered communities that form around these crafts. The poems also respond to the cultural treatment of craft knowledge as frivolous or simple, highlighting the highly technical nature of such work and the mathematical, structural, and geometric knowledge required to successfully execute textile crafts. Densely referential, these poems invite the reader to play within their sounds and associations, making her own leaps and connections as she reads.

All the Lovely Ladies

Bless me, you Ladies of floss and

fiber who have bowed your heads

over tricky tapestries, crossed Xs in red

silk as I cannot write, pricked testaments to 1

wicked design or ill-use, rage

subsumed in rags cut to patches or pale

stitches satining smooth scenes

from The Turkish Embassy Letters.2

Bless my hands and make them cunning

let me twist and knot as you have shown.

Give me counting to button my lip

and friction to join together

lickety-spit and slip me down beneath

the notice of those whose notice

I do not need, let me front

and back into mathematically doubling

ruffles fluffed and fussy gathered

camouflage over my breast, make one,

pick up and

Careful Ladies,

I have pledged my thumbs to picot-edge

hems, I have dedicated these two millimeter double

point needles to turning round

heels. Bind me off into the serenity

of work and deliver me unto

idleness, blocked stockinette, heat passed

from one body to a hotter

sweater,

Oh Ladies of quiet coverlet

bless me; I consecrate my hands to

your samplers your silence

your what will become of my soul.

1 italicized text is from the Elizabeth Parker Sampler, ca.1830

2 written by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in 1716-18 and published after her death in 1763

Celestarium

A fixed point is a fiction, yet sailors and children

still feel the attraction—and a course that’s plotted

to follow a star or a yarn is usually able to guide

for a while at least, before winding out. Look,

I’ve already set one in place, just here. A bead drawn

over my center stitch with this slender crochet hook

my mother gave me. It’s steel, sharp as a needle,

and tiny enough to knit through a bead; I usually

keep it in an old wooden tube with some fine knitting wires

my great-grandmother used. Now the bead is in place

so it’s safe to unspool the whole afternoon around a pattern

or two. Settle into the pleasure. Memorize the repeat,

then chant it back as you knit; see your catechism

captured in inches of stitches. The first bead

stands for Polaris, a silver fancy of constancy

knotted at the heart of the fabric. The pattern’s a version

of Zimmerman’s Pi Shawl, one of many constructions she wrote

down for knitters. She called her discoveries unventions; said

they were really more realization than design, and yet—no one

had knit these until she wrote them down. Pi Shawls are a constellation

of creations, all predicated on the properties of a circle

in the Euclidean system of geometry. Euclid, you’ll note,

was a man, and did not call his various realizations

and equations describing spaces and shapes un-anythings.

Well. The thing to remember when planning

your Pi Shawl is that all dimensions grow

by the same factor and at the same rate. The shape

is a circle and the factor is double. Of course, a cape made

with beads that are charted like stars only locates

or means if we take this planet, now as an assumed

perspective. A parsec shifted or spun and the work

that you’ve done in your hours of knitting

is wasted: so much un-navigable galactic gibberish.

(But go on!

It’s still pretty!) Half the stars I’ve strung along

are ones that burned out years ago (not that years are meaningful

in any way to stars in other galaxies, or even long enough

to be a useful ticking length around a clock the size

a star would need). Still, here and now are often reasonable

assumptions. And these days when a snarl knots the working skein

the answer is to twist around and switch the yarn.

Change your hero’s colors. Perhaps you cried

when Icarus lost wing and died, but, kiddo, hush,

you can’t believe it. Instead let’s say his name was Felix

and he was happy in his fall. It’s what the corporate

sponsorship was paying him for, after all! And to assist

in his descent his Faerie Scientist invents a special

pressure suit of crocheted net to cushion

all his squashy bits and save him from hypoxia—

oh, I know you heard some flap of wax

and melting, but that’s distorted tattle.

Those who’ve seen him say it’s more a case

of candle-lighted tête-à-tête with this admiring fan

and that, a model first, a playmate next,

or maybe in between there was a former beauty

queen? They flicker in and out since Felix’ fall

to sudden fame. Wait, I need to count.

Okay, right.

Zimmerman’s unvention allows a new story to begin with every increase round.

But! There’s a catch Scheherazade would hate, unless it’s one

she would appreciate? I’ll grant that it’s a rule

bound to make a Sultan beg for sleep within a week

if he’s to hear a tale in full and start a new one every night

before he blinks. But then again, it’s safe to bet Scheherazade

was clever with a well-placed cliffhanger, and why not wind

each story out in sequels, season twos, perhaps a wacky

spinoff? Here’s the rule: each story must be told on twice

as many stitches as the last, and lasts for twice as many rounds.

Other than that, your hands may loop as they like,

plumping bobbles or dropping steeks, or, sure, passing

hours every day and eve slipping silver-lined seed

beads into place to shimmer like the stars some sailor

once remembered by making up this constellation, this Cassiopeia,

this Ursa Some-or-Other. Stars have always been straightforward

lies, haphazard blips of time and wave, a random cross

of stars and galaxies from myriad assorted times, most

of which reside in completely different parts of the universe

from their apparent neighbors. But wanderers persist

in yearning; a woman names her child Astrolabe,

or learns to use one, and every tale would seem a random happen-

stance if it were poorly woven.

Stitch whatever structure

long enough, eventually it’s hard to see beyond it. Finish it

tonight you think or find yourself without a stitch

that’s fit to wear tomorrow. The wool in your hands becomes

the only cloth in the world that matters. Everything beyond

unravels. You cannot see it. Those other stories have been told,

and are dead.

Hook a bead over a stitch to stand for Orion’s

Alnitak, knit twice around before you place

another one for Alnilam, or, no,

go back.

Unknit and place them once again, but better name them

Freya’s Distaff. There’s a terrible website that draws children just like me and you

into our doom. It’s called howmanytimeswillyouseeyourparents

beforetheydie.com. I don’t know why, but none

with living parents can resist it. After the inevitable shipwreck,

seek comfort in repair; try teaching yourself to darn

your fraying garments. Good luck! For this to work,

you must focus only on the worn elbows of your favorite

cashmere sweater. The stiff new threads are woven, stretchless,

into the sleeve. Above, below, above, below, then back

the other way. Don’t think of your heart harbored in the eye

of a tapestry needle. Know it’s wearing out, and that means

it’s alive. It’s a tiny horizon, all stitched up and everywhere:

keep your eyes inside it. This is a different kind of telling—I’m sorry,

did you think we were still sailing towards Orion? keep up!

The hour’s turned, the sky is late, the row’s increased, and now

our heading is The Lion! Azimuth is meaningless in flat

coordinate systems, but let’s not let such points

constrain us. It’s one more chance to break the yarn

and join a story in that men

of science never thought

of picking up, the kind your grandmother would tell

her friends: a formula for crochet booties, a brave campaign

for voting rights, perhaps a throbbing cock and to go with it

some anachronistic British duke who read bell hooks and loves her

very much. By now you realize I’ve gone awry, I’ve

botched it up, I’ve missed a stitch or skipped

a row, I need to frog it back at least a chart. I cannot

bear it. No matter what that rocky website says, today

there’s still a hope for when I’ve made mistakes the scope

of which entice me to give up and quit:

I call my mother.

She’ll take the work of ripping out and hand me back

a second try at getting all the strands aligned.

It’s not the added work that sometimes leads to UFOs,

it's the debriding.

Thank heavens we’re the lucky few whose moms

can do this work another time or two before they die.

But, dear, when you’re alone, I’ll kindly, lovingly

rip out your work, or if you’re far away a lady at the local

knitting shop will almost always walk you through it. It’s not

so bad, you’ll see, here, hand it over. For comfort

while we work, I’ll tell my favorite tale again: pressure suits

for astronauts

are made by hand. A thousand individual pieces

a physicist designed are sewn together on old Singer

sewing machines and wrapped around a human

form and fired into space and somehow snug inside

the lungs can still inhale. If sturdy wooden tables

in an old tailor shop in New England are where they drape

what’s all the rage to wear in space I guess it’s scientific fact

that when you face the void, a stranded yoke, some plaited

6-stitch cables, perhaps a brioche cowl in tweedy wool? These

garments are best suited to protect you. They’re twined

and tough. You taste the horror vacui? Here, I’ve torn it back,

the stitches that were missed or twisted are unknitted; there’s

the dish of beads. Hook one in. There’s still time. Begin again.

“Celestarium,” “All the Lovely Ladies,” and Craft Rhetorics

Celestarium

“Celestarium” is the name of a knitting pattern available for purchase on ravelry.com, a social networking site for knitters and crocheters. My poem “Celestarium” adopts the same title because the poem was initially drafted over the course of the year it took me to knit the shawl, and in part explains how the shawl is made.

The knitting pattern is for a circular shawl based on the Pi Shawl, which was designed by knitter and designer Elizabeth Zimmerman (perhaps best known for her 1971 book Knitting Without Tears). The Pi Shawl pattern is loved by knitters in large part because the increases are worked so as to allow enormous design freedom for customization. To knit a Pi Shawl, you work outward from a center stitch, knitting, say, three rounds even, then doubling the number of stitches, then knitting six rounds even, then doubling your stitch count again, then twelve rounds even, and so on; each concentric section of the shawl is thus knit on twice as many stitches as the previous, for twice as many rounds. But between the increase rounds, you are knitting on a stable number of stitches and don’t have to work constant, incremental increases which can make patterned stitches like lace or cables difficult to manage. Many Pi Shawls are essentially lace samplers, with each section used to perform a different lace design: a rose, a leaf, a slanting lattice.

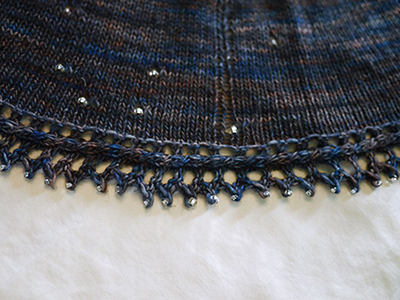

In “Celestarium” as I knit it, however, apart from the increase rounds, all stitches are knit—no yarn overs, no purls, no complex lace patterns. Most of the shawl is the easiest sort of knitting there is, save for one thing: seed beads are periodically crocheted onto stitches so as to reproduce a star chart of either the entire northern hemisphere, or, if you prefer, the southern hemisphere. My own version of the shawl, then, is based on the principals of the circular shawl Zimmerman originally identified, and on the star chart Audry Nicklin created for “Celestarium,” but adds my own variations: first, Nicklin’s pattern does include “yarn overs” next to each bead. When included, the yarn overs create a small hole next to each “star,” and I eliminated these.

Second, Nicklin’s border is simple, just five rounds of garter stitch. I wanted something more elaborate—I had in mind something that would evoke the points of a compass rose on an old map—and ultimately ended up with a combination of a cable and a picot lace worked back and forth, where each picot point is tipped with a bead. However, this border was considerably less elaborate than the one I originally envisioned, and that was mostly because I was running out of yarn: I actually had to swatch several versions, measure and weigh each one, then calculate against the total weight of my remaining yarn to see if it would reach around the circumference of the finished shawl.

Knitting “Celestarium” thus brought me into collaboration and community with the technical knowledge and design sensibilities of many women: Zimmerman and Nicklin, knitters whose patterns I combed through for border ideas, and knitters who had already worked the pattern in various yarns and with various alterations and posted their experiences on ravelry.com. It also brought me into conversation with natural constraints created by my materials.

Celestarium border

Such communities, collaborations, and interactions with the material world are central to not only my own creative work, but also to the concerns of a growing body of contemporary scholarship on craft rhetoric. In their article “The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power,” Heather Pristash, Inez Shaecterle, and Sue Carter Wood argue that though women’s traditional textile crafts—sewing, knitting, embroidery, and so on—have historically served and can still serve to imprison women within the home and symbolically chain women to the domestic sphere, crafts and the time spent making them also function as a space for woman-centered stories to be framed and shared among (and beyond) communities of women. They draw on Joan Radner and Susan Lanser’s (1993) descriptions of the “coding strategies” used by women and other marginalized groups, identifying textile work as a medium that can communicate with subtlety to other knowledgeable crafters in ways that are invisible or seem irrelevant to outsiders, and thus name it a “frequently coded practice” (Pristash et al., 2009, 15). Pristash et al. acknowledge that “[h]istories of needlework demonstrate that the needle has been a vehicle for women’s construction by the dominant discourse,” and histories, literature, and popular culture have all used needlework in a variety of ways to associate the domestic with “womanliness” and femininity.

However, they go on to argue that because of its capacity for coding, “the needle has also been a vehicle for women’s own construction of alternative discourses, discourses with the potential to expand women’s discursive worlds and the power they wield over their own lives” (2009, 13). That is, working with textiles is an inherently creative endeavor, and as such cannot help but simultaneously give women a rhetorical space for speech, though that speech may be deeply encoded.

Scholarship further suggests that traditional textile craft continues to serve as a “vehicle . . . for construction of alternate discourses”—as a medium that allows artists and activists to produce counternarratives and push back against stereotypes—in contemporary craft and craft activist movements. For example, Jack Bratich and Heidi Brusch (2011) have argued that public knitting has potential as a component of civil disobedience because it is both visibly nonviolent and yet, because it is usually associated with the home rather than with public space, visibly disruptive when performed in such spaces.

Additionally, Nicole Dawkins (2011) has explored how traditional craft and “DIY” practices in Detroit were routinely spoken of by young artisans and crafters moving to the city as choices made individually, for reasons of personal pleasure and fulfillment. Members of the crafting community spoke of how their bohemian lifestyles formed a vibrant maker movement in the wake of the financial crisis—but Dawkins also shows that this way of talking about their work allowed them to form an exclusively white community within a historically black area of Detroit. Their claims of personal pleasure and fulfillment also relied on neoliberal labor narratives and obscured the precarious and arduous nature of craftwork as a livelihood in contemporary urban America.

Fiona Hackney (2013) perhaps most directly connects Pristash et al.’s analysis of historical craft rhetorics to contemporary craft practices, as she, too, sees craft practices and discourses as deeply gendered, and argues that nuanced gender performances continue to be central to what and how traditional textile craft communicate both within and beyond the craft communities where they are produced. Also like Pristash et al., Hackney argues that both the time for contemplation provided by needlework and other crafts traditionally practiced by women, and the knitted, embroidered, and otherwise crafted items produced have been and can be valuable to women in allowing uniquely feminine voices to develop and speak from within patriarchal structures.

This scholarship resonates with my own experience of both knitting and sewing, the two textile crafts I have most consistently practiced throughout my life, and the concerns are central to the poems I have been working on over the past two years. I am fascinated by the way language is incorporated into textile crafts by the various codes and communities that form around and about craft practices, the stories that are told or that form in the course of creating craftwork, and the way textile craft itself functions as a language. “Celestarium” and “All the Lovely Ladies” are both pieces in a larger poetic project that incorporates these languages and stories from multiple directions.

In the case of “Celestarium,” the structure of the poem loosely imitates that of the shawl itself, and while each section does not double the length of the previous section (a formal element that would grow unwieldy rather quickly), it does periodically “change design” by switching to a new topic or introducing a new theme. My hope is that these shifts, in addition to mimicking the Pi Shawl’s potential to change and collage multiple designs, also reproduce the type of discourse I have experienced when sewing or knitting in company with other women, where stories are shared in turn to pass the time: one story leads to another, sometimes a period of silence is ended when the meditative quality of the work at hand leads someone to a thought or memory worth sharing, and questions of design and technique punctuate personal narrative or political discussion.

My methods for engaging textile craft and the surrounding discourse are further influenced by those of other women poets who have interrogated both poetic form and language itself as systems that have historically devalued or dismissed woman-centered stories and experience. Megan Simpson argues in her book Poetic Epistemologies that “linguistic innovation offers many women writers ways to pose questions and suggest possibilities about issues of knowledge, subjectivity, language, and gender that more conventionalized modes of writing might obscure or take for granted” (2000, 5). The inclusion of quotations or text collaged from other sources is one such method of undermining any sense of narrative—or even speaker—as singular and entirely authoritative.

Marianne Moore, for example, often incorporated unmarked quotes from non-literary sources such as magazines or popular non-fiction texts—issues of Scientific American and The New York Times; Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler; Alan Trachtenberg’s Brooklyn Bridge: Fact and Symbol—into her poems in a way that suggests to the reader that the language and content of poetry need not derive only from familiarity with the classical tradition or Greek literature. Alice Notley, in poems such as “White Phosphorous” and Descent of Alette, uses quotation marks surrounding short phrases—none of which seem to be actual quotations from other sources—to suggest a patchwork text that complicates any sense of a single or coherent speaker.

My own work is informed by such means of “suggesting possibilities.” I do borrow language from non-literary sources. In “All the Lovely Ladies,” quotes from the stunning Elizabeth Parker Sampler, an early nineteenth-century cross-stitched autobiography that documents Elizabeth Parker’s assault by an employer, attempted suicide, and subsequent spiritual crisis. The sampler begins with the phrase, “[a]s I cannot write . . . ,” a rhetorical move with complex implications for Parker’s comprehension of the term “write” relative to “speak,” “read,” or “communicate.”

Where “Celestarium” attempts to capture some of the process of crafting and elements of the experience of knitting, “All the Lovely Ladies” more directly engages sewing, knitting, and embroidery as gender performances, attempting to both suggest and question ways domestic textile work might protect women (of certain classes and abilities) by making them appear innocuous, quiet, dainty, demure, and submissive—qualities long associated with the feminine and used to categorically marginalize women, but which can potentially be subverted and exploited as cover for rebellion and organization.

I also attempt to, in some sense, “collage” or “quote” from material objects in my work. My focus on craft items rather than the high art forms typically associated with ekphrastic poetry mirrors Moore’s use of popular sources. Through mentions of mending and of work “torn out,” I further attempt to introduce gaps, shifts, and the echo of other voices into “Celestarium,” using the association with the processes of craftwork to complicate any sense that the poem’s narrative is singular, inevitable, or permanent. As I have reworked myth, history, and design, readers are invited to play within the sounds and retellings that surface in the poem, making their own associations and leaps as they read, and perhaps even finding a pattern worthy of further alteration and reinvention.

Danika Myers is a member of the University Writing Program faculty at George Washington University. Her work has previously appeared in journals including Beloit Poetry Journal and Forklift, Ohio. She lives in Baltimore, Maryland, and spends her free time starting more knitting projects than she finishes and running very, very slowly.

References

Bratich, Jack Z., and Heidi M. Brush. “Fabricating activism: Craft-work, popular culture, gender.” Utopian Studies 22.2 (2011): 233-260.

Dawkins, Nicole. “Do-it-yourself: The precarious work and postfeminist politics of handmaking (in) Detroit.” Utopian Studies 22.2 (2011): 261-284.

Hackney, Fiona. “Quiet activism and the new amateur: The power of home and hobby crafts.” Design and Culture 5.2 (2013): 169-193.

Pristash, Heather, Inez Schaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood. The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power. na, 2009.

Radner, Joan N., and Susan S. Lanser. “Strategies of coding in women's cultures.” Feminist messages: Coding in women’s folk culture (1993): 1-29.

Simpson, Megan. Poetic Epistemologies: Gender and Knowing in Women's Language-Oriented Writing. SUNY Press, 2000.