The “Hatting” of the Clock: Crafting Juniata’s Knitting Community through Yarn Bombing the Clock Tower

Hannah Bellwoar and Scarlett Berrones

This piece explores how knitting creates community. We’ve found that the materiality of knitting, by which we mean the physical making of knitted objects, creates a feeling of community that connects people across physical and digital spaces. We discuss how the authors’ personal knitting experiences with a college knitting club and yarn bombing the clock tower on campus relate to theory about the materiality of making knitted things. We argue that crafted rhetorical actions such as the yarn bomb enable knitters and non-knitters to connect more broadly around central community spaces.

Introduction

“DIY citizenship potentially invites us to consider how and when individuals and communities participate in shaping, changing, and reconstructing selves, worlds, and environments in creative ways that challenge the status quo and normative understandings of ‘how things must be.’” —Ratto and Boler, DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media, 2014

Yarn bombing, once called “guerrilla knitting” and sometimes considered illegal, has been making headlines. The activity of covering public objects with knitted or crocheted pieces may, as Ratto and Boler express, be challenging the status quo. At the very least, knitting—an activity that once was the private, personal activity of women—seems to be intersecting with public spaces in interesting ways through acts of yarn bombing.

We, the co-authors of this article, participated in a yarn bomb in November 2014. We are both active in the college knitting club. Hannah has been knitting for 13 years. She is an English professor at Juniata, and she is co-advisor of the knitting club. Scarlett has been knitting for 3 years. She is a student at Juniata, with a Program of Emphasis in Integrated Media Arts, and she is Vice-President of the knitting club.

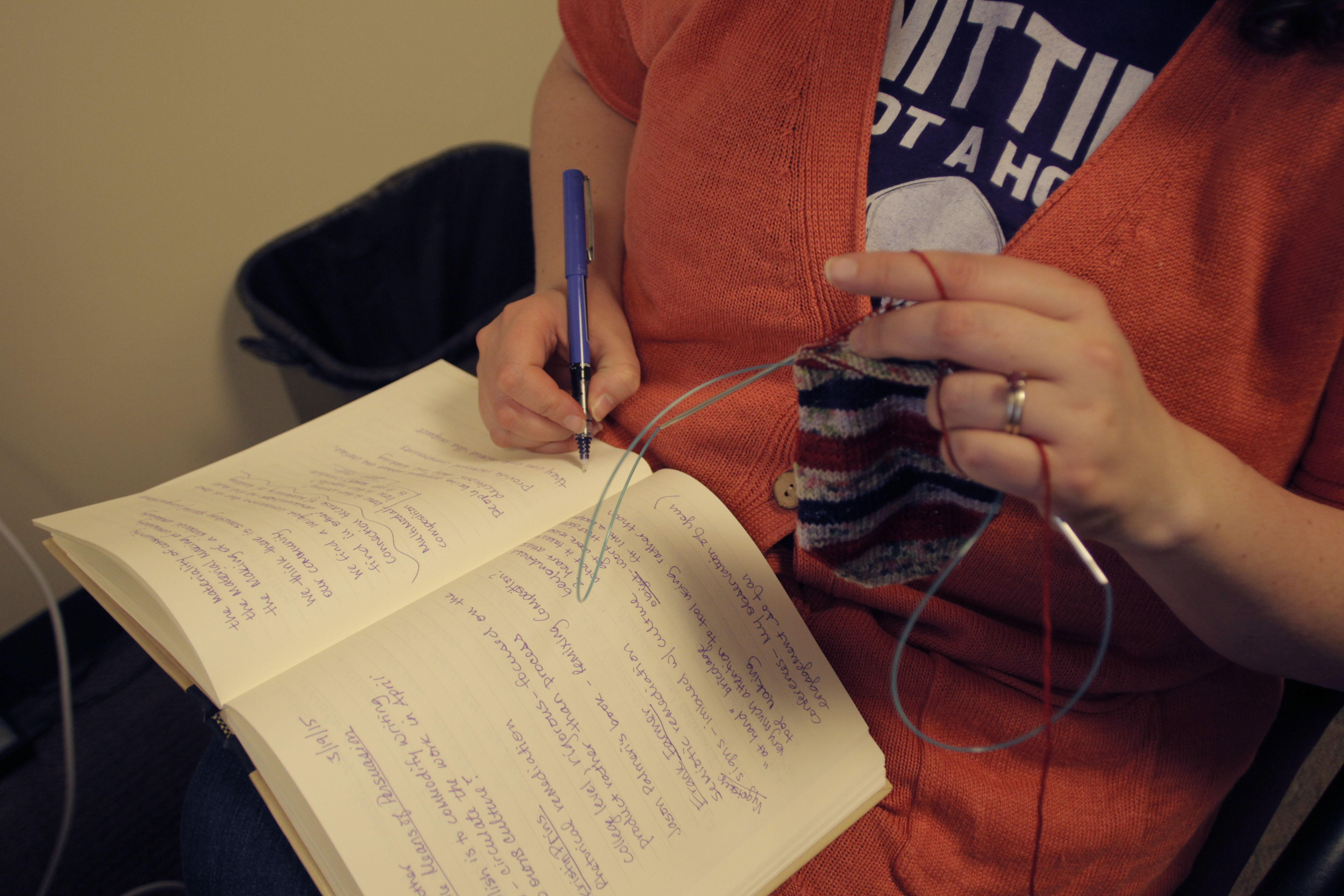

Scarlett and Hannah talking and knitting together

Through our participation in knitting club and the yarn bomb, we find something unique: the materiality of knitting that brings communities of knitters and non-knitters together. We define materiality as the process by which the objects are made, one stitch at a time, as well as the product of knitting, the physical hat and scarf and sweater that comes out of the knitting process.

Knitters know the importance of the materiality of knitting because they experience the making that's involved. Knitters don’t like to knit for non-knitters for fear they won’t appreciate the hours of work that went into it, and they’ll just put it in the dryer.

In what follows, we discuss the materiality of knitting, particularly yarn bombs and other public knitting practices that make connections between personal and public spaces that are not easily articulated through language. Hannah has tried to use language to articulate what is unique about knitting communities before, and she’s talked to Scarlett about it in depth, but we both struggle to communicate it. Words don’t seem to be enough, so for this article, we decided to communicate it through words, pictures, and videos.

Materiality

To better communicate the materiality of knitting in the process of making knitted objects, we start with a story, told by Hannah:

It's a story of materiality in one particular moment, as I knit, listen, write, and think at a conference presentation. While the knitting might seem obviously material because it is both object and action, it can be easy to forget that thinking, listening, and writing are also material practices. This narrative shows how my thinking, listening, and writing are inseparable from the materiality of my knitting.

I am at at the 2015 Conference on College Composition and Communication, a professional conference for people who work in Rhetoric and Composition, sitting in an uncomfortable hotel chair. I’m listening to a panel on Jody Shipka’s work on multimodality, which is communicating through different modes, such as the language, images, and gesture on this website.

I have my favorite Paperblanks journal open across my crossed legs, and I use my purple Pilot pen to take notes and write musings about whatever resonates with me as I listen. I love the way the words look on the page, written in color, and I often turn the pages of the journal, thinking about what I’ve written before.

On the floor next to me, on my left, is a small project bag, made with Alice in Wonderland fabric. While my right hand holds the pen, wrapped around my left hand is the yarn from the sock project I am currently knitting. I periodically put the pen down, knit a few stitches, and pick the pen back up to write something else down in my notebook. I love the way the partially finished sock looks as it rests on the pages of my notebook.

Hannah writing in her notebook and knitting

The speaker, who is currently Jason Luther, is talking about his students publishing zines and distributing them as a community on a particular day. I immediately think about the materiality of knitting communities, and it occurs to me that perhaps what is unique about knitting communities is the fact that we are all making something. And then, I start to play with these three words on the right side of the page: material, making, community.

I put down my pen and knit. The red stripe is complete, and the yarn color changes to pale purple speckled with green. The speaker, who is now Kristin Prins, references a story in the introduction to Shipka’s book Toward a Composition Made Whole, where Shipka discusses a teaching assistant's reaction to a student project, a pair of pink ballet shoes on which a student had “transcribed by hand a research-based essay” (2).

I’ve heard this story before. However, this time, I hear it differently, as a story about making visible the processes of making.

Frank Farmer is speaking now, and he says that we pay more attention to tool using than tool making. I think about my knitting needles, the tools I’m using to knit my socks. They are metal, smooth, and the stitches glide across them rhythmically. I think about the talk I went to about 3D printing at my college last year.

I left that talk wondering how the world would change if we could use 3D printers to manufacture things completely differently. I also wondered how knitting would change if I made my own needles using a 3D printer.

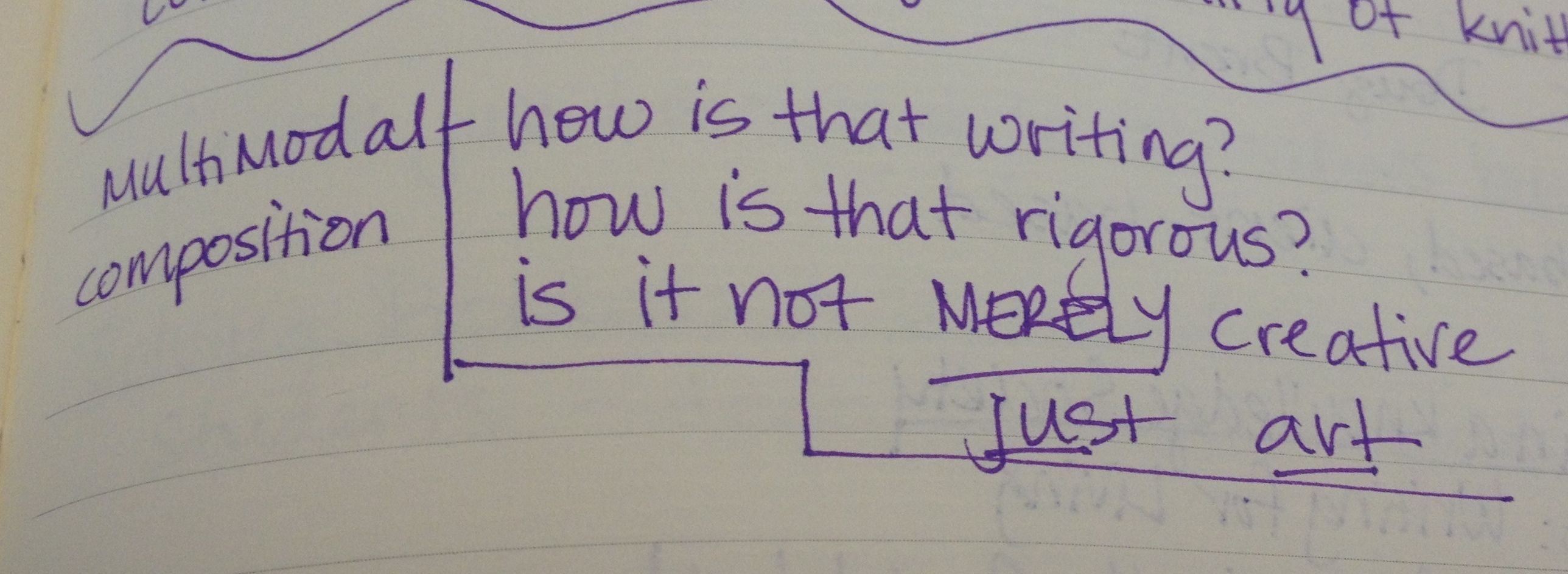

Shipka is now responding to the speakers, and she says something about multimodal composition that resonates. The assumptions of the teaching assistant when he sees the pink ballet shoes—

Assumptions about multimodal composition

In the book, Shipka says,

“My sense is that his attention was focused primarily on the final product, while I was positioned—by having created the assignment, the course itself, and having worked closely with the student over the month she spent working on the shoes—in ways that allowed me to see, and so to understand, the final product in relation to the complex and highly rigorous decision-making processes the student employed while producing this text” (3).

Shipka ends this talk by referring to a recent class of hers where students brought in yarn and knitting needles. One student took a picture and posted it to Instagram with the hashtag #college. Shipka calls attention to how we might feel if we were given a set of needles and yarn and told to just knit. Frustrated, confused, and annoyed with the teacher come to mind. How is the teacher going to give me the tools and materials, but not teach me how to actually knit?

I am humbled. I wonder how often as a teacher I do the same thing. How often do I put tools and materials in front of my students without teaching them to use the tools?

By bringing yarn and needles to class and telling the class to “just knit,” Shipka’s students were making a profound statement in a simple way to their audience of the class. However, like the ballet shoes, the yarn and knitting needles are part of what Shipka calls more “complex and highly rigorous decision-making processes.” These processes draw on knowledge of the materiality of knitting.

Making Something

In the previous example, knitters and non-knitters see the knitting needles and yarn completely differently. For a non-knitter, these tools might be frustrating, confusing, and annoying. For the knitter, these tools might be calming, creative, and centering. The same tools represent very different emotions depending on the audience member’s knowledge and experience. In a sense, the process of knitting itself becomes something that divides knitters and non-knitters.

Arm knitting

If you are a non-knitter, what follows in this section may not make sense to you. This is because the process of knitting can be a text to the people who have the skill to read it, and who understand the language, where the language is physical as much as something intellectual.

Here is an example of the “complex and highly-rigorous decision making” that goes into the processes of knitting, told from Hannah’s perspective:

My decisions included color (striped red, white speckled with green, purple, light purple speckled with green) and blend (75% wool – warm, wicks away moisture, 20% nylon – sturdy, makes the socks last longer before developing holes, 5% other – sparkly, 'cause it looks pretty). Also, this yarn was dyed by the company Desert Vista Dyeworks (DVD) in the colorway “Zombody loves the Knitgirllls.” DVD dyes many Zombody colorways, and they are cool—the speckled stripes look like zombie splatter.

The Knitgirllls are some of my favorite knitting podcasters, creators of one of the first video podcasts about knitting. I’ve spent many days alone watching their podcasts, knitting along, and feeling a part of a community. Podcaster Leslie’s favorite color is red, and Laura’s is purple. And incidentally, my husband and I chose red and purple as our wedding colors because when we play board games, he likes to play red, and I like to play purple.

Two knitters enacting a material process

My process for choosing needles was complex—I first started knitting socks with four double-pointed needles, but they are fiddly because you have to switch from needle to needle, and it’s hard to not poke myself a lot with the ends. I switched to two circulars, but when knitting in public, I was always hitting people with the ends of the needles I wasn’t using.

I switched to magic loop on one long circular, and once tried knitting two socks at a time, but I hated that. Too fiddly—my two balls of yarn kept getting tangled.

Now I do one sock at a time magic loop. I prefer metal needles because the yarn glides quickly over them, and knitting is faster. I prefer addis or hiya hiya sharps because the pointy tips make it really easy to get into the stitches. And I typically knit with size 1/2.25mm needles because they make a fabric that is dense enough to hold up to wear with most sock yarn.

Choosing the pattern also involved complex processes, and I’ve finally settled on knitting socks toe up, using Judy’s magic cast on, the fish lips kiss heel, 1 inch of 1 by 1 ribbing, and Jeny’s surprisingly stretchy bind off. I’ve tried a million different cast ons and bind offs, but these make what I consider the neatest toe and the stretchiest cuff. Neat isn’t that important, but a stretchy cuff is or otherwise some folks can’t stretch them enough over their ankles to get the socks on.

Circular knitting

I bought the fish lips kiss heel pattern on Ravelry, a social networking website for knitters. I love the fish lips kiss heel because it’s easy, fits nicely, and is durable. I don’t read and follow patterns for socks anymore; I’ve got this one memorized, and it’s become a part of how my hands work now.

How much of what I just said do you understand? Did you think knitting involved such complex processes?

Most non-knitters look at knit objects and see the thing—maybe the color and how it will match with their wardrobe, possibly the pattern if it’s fancy. When knitters look at knitting, we see the stitches. We see the pattern in our heads. We compare it to other things we’ve made.

For knitting, like other crafts, we use more than our hands, our eyes, our minds—we use our bodies, the fingers attached to our wrists, attached to our arms, attached to our shoulders, attached to our backs, attached to our necks, attached to our heads, attached to our eyes. We make something with our physical selves. We concentrate on counting the stitches, following the pattern; we relax our bodies and move to the rhythm of completing each stitch.

Knitters know not only what knitting looks like but what knitting feels like. These aspects of materiality might separate knitters from non-knitters, but they also help form community amongst knitters who understand the process of knitting.

One place where we’ve observed this happening is in the space of Juniata’s knitting club. In Scarlett’s video, we hear club members talk about the ways they’ve connected through craft in the knitting club.

Our knitting club meets weekly in a dorm lounge. As Henry says, he found knitting club because it met in a public space that he walked by regularly. Knitting club is a place, according to Kim, where we can be productive with our hands. Wendy says that knitting club allows us to come together and bounce ideas off of each other so we can learn better ways to do things. For Lexi, knitting club is a place where club members can bond, because knitting gives them a strong feeling of camaraderie.

For Scarlett, knitting club is a space where it doesn’t matter what you study or what year you are in college. Despite our differences, we all have this physical, material practice in common, a practice that is important to us.

For Hannah, it’s a time to spend with students that isn’t constrained by evaluation, a space where we can commune over something that we love that doesn’t have any stakes in our work lives—nobody gets graded or evaluated, we can just be who we are and make mistakes, sharing the making of something we love with other people who get it.

Sharing Material Communities

In the previous sections, we have shown how our shared understanding of process and how knitting together can bring knitters closer together. In this section, we discuss our yarn bomb project in more detail to show how the physicality of knitting can also bring knitters and non-knitters together.

Yarn bombs can be shared in two ways: in physical spaces where spectators view everyday objects like staircases or statues that have been covered in yarn, or in digital spaces through photos or videos of the yarn bomb. These material practices that knitters share in physical and digital spaces bring what was once considered private and personal (knitting) into the public sphere, which can be an act of DIY citizenship.

DIY citizenship is grassroots organization of community that can possibly challenge the status quo. The story of our local knitting club collaborating across campus challenges the status quo in multiple ways—across gender lines, across lines of privilege between faculty, students, and staff. What we know through the materiality and making of knitted objects is more important than the lines we find drawn seemingly arbitrarily around us.

Knitting Club knitters at work

Here is the story of our yarn bomb, told from Hannah’s perspective:

When my friend Belle came up with the idea to yarn bomb the clock tower on campus, five of us, both faculty and staff, came together to knit a hat for the clock tower. Kim, a math professor, was tasked with figuring out how big the clock was and writing a pattern for it.

I could never make it to the meetings, but Kim took notes and emailed me a picture of them taken on her iPad. Belle ordered the yarn in blue and gold, our school colors, and we each got started knitting a wedge of the hat.

It was truly a collaborative effort. Val and Genna, staff members in HR and Marketing, and Belle, Kim, and I each knit a wedge, and we passed needles and yarn around from person to person. Kim and Belle knit wedges with the letters “J” and “C” on them, using a technique called intarsia, to stand for Juniata College. Kim knit my ribbing for me since I hate to knit ribbing. Belle sewed all five wedges together.

I tried to make a really big pom pom to put on top, but instead it ended up being rather small compared to the size of the clock. Meg, the educational services assistant, organized facilities to come safely put the hat on top of the clock for us.

About 10-15 student club members met each week and knit squares for the yarn bomb as part of a service project. The knitting club has completed several projects together, from donating hats and scarves to a local women’s shelter to making knitted hearts to sell on Valentine’s Day. They sometimes take field trips to local yarn shops to enhance the club atmosphere. For this project, knitting club students knit squares and sewed them together to make a scarf to go with the clock tower's hat.

On a rainy day in November, a group of us armed with cameras and a large knitted hat and scarf trekked out onto the central quad to watch, participate in, and record the yarnbombing. The hat that once swallowed Belle up looked a lot smaller once placed on top of the clock. The scarf blended into the background once weaved into the “neck” of the clock. Once the hat was stretched out, it covered the clock tightly, and the letters “J” or “C” were visible no matter from which direction you approached.

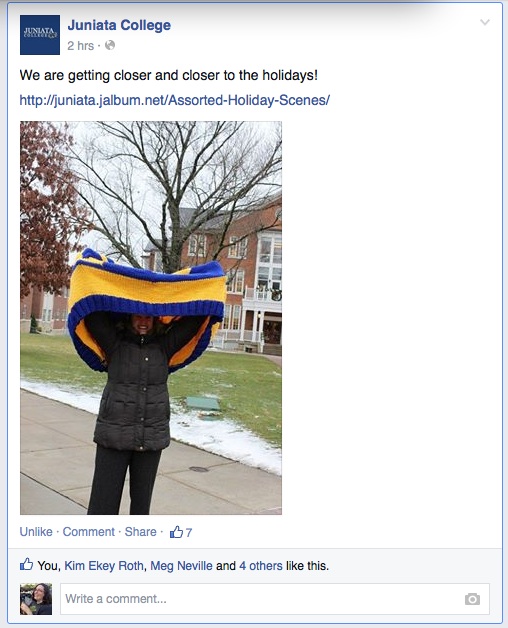

From the main street on campus, you could see the hat as you drove by. The pictures were shared centrally on digital spaces as well—on social media such as Facebook and Instagram, and on Juniata’s website. And we share the yarn bomb again with you here, too.

The yarn-bombed clock tower

Orton-Johnson calls the sharing of knitting on digital spaces “digitally mediated maker identity” (145). She says,

“At the level of online community involvement, this shared sense of experience, belonging, and identity is of course nothing new. However, these forms of materiality and connectivity enable community members to present their identity as ‘maker’ and to express their creativity in ways that provide a sense of meaning and value through and in craft-specific online communities, again connecting the identity of creative maker with wider community networks of DIY citizenship” (147).

The yarn bomb was truly a collaborative effort that challenged the status quo between students, faculty, and staff. In our everyday lives, each group completes a lot of individual work, but rarely do all groups work together. Additionally, knitting club has several male club members who knit squares for the yarn bomb. Knitting has been seen as women’s work, but in this case, our collaboration crossed gender lines.

However, the community’s primary purpose in coming together wasn’t to challenge the status quo. It came together to knit something big and display it in a public space. In Scarlett’s video, she asked club members why they participated in the yarn bomb and what they thought of it.

Henry said it was a perfect representation of Juniata—goofy and weird in a good way. Ramsay said it was a cool thing that showed our school spirit and brought us together. And Scarlett said everyone can see the yarn bomb; it brings awareness that knitting club is not just there, but is actively doing stuff, actively participating in the community through making knitted objects.

Thus, Orton-Johnson says though examples such as these are less politically oriented, this “highlights the need to understand motivations that articulate around alternative definitions of participation and citizenship as a form of leisure and pleasure of collaborative connectivity” (151).

Facebook post about the project

In cases of DIY citizenship motivated by craft rather than political change, the connections made across digitally mediated spaces such as Facebook and Ravelry and the identities of “maker self” that are constructed online create what Orton-Johnson calls “a new form of materiality and connectivity” (152).

Hannah and Scarlett have found this to be true in our sharing of material making with each other and with you. The complex decision-making processes that went into making this essay and documentary came about through many hours of meeting, thinking, developing questions, shooting and editing video, writing and researching material practices and digital representations of these practices. In our time together, Hannah and Scarlett also spent time thinking about knitting club.

We thought about what is important to us about knitting and being a part of a knitting club and participating in a yarn bomb. We thought about what we like to knit, and who we are as knitters, our maker identities.

At the end of every project meeting, Scarlett would bring out knitting, and Hannah would be excited to see her progress, her experimentation with new projects, and her purchase of new beautiful yarns. Scarlett would ask questions about some new technique she’d never tried before. Hannah hated to see her knit alone, so she would bring out knitting, too, and we’d take a few minutes to chat and knit together, enjoying each other's company, a welcome respite from the hard work of this writing and video project.

Hannah Bellwoar is an Assistant Professor of English at Juniata College. In addition to knitting, she enjoys crochet, spinning, and cross-stitch. She loves knitting socks especially, showering approximately 150 pairs on friends, family, and perfect strangers. She collects yarn wherever she or her knitting proxies go, including Alaska, Hawaii, the Florida Keys, Hungary, and the Philippines. She suggests you can tell a lot about the local culture by the kind of yarn they have, so wherever you travel, scope out the local yarn stores first!

Scarlett Berrones is an undergraduate student in Multimedia Communication at Juniata College. If there’s anything you need to know about her, it’s that she spends way more time looking for patterns to knit than she spends actually knitting. Hats and monsters are her specialty, but she loves an occasional scarf or pair of socks. She is endlessly searching for opportunities to include knitting in her daily activities, schoolwork, and multimedia projects to show this craft's significance in every aspect of life.

References

Orton-Johnson, Kate. "DIY Citizenship, Critical Making, and Community." In DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. Matt Ratto and Megan Boler, Eds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.

Ratto, Matt and Megan Boler. “Introduction.” In DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media. Matt Ratto and Megan Boler, Eds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.

Shipka, Jody. Toward a Composition Made Whole. Pittsburgh, PA: U of Pittsburgh P, 2011.

Wolan, Malia. “Graffiti’s Cozy, Feminine Side.” New York Times, May 2011. Web. 22 Aug 2015.

Yarn Bombing Bolardos by Teje La Araña 2, Wikimedia Commons