Writing in the Moment: Social Media, Digital Identity, and Networked Publics

Jacob Babb

Why do we post to social media? What leads us to withold some aspects of ourselves and share others? This article emerged from a moment of disruption that led the author to these questions. The article addresses different examples of social media usage, such as the recent Internet outrage regarding Cecil the Lion, to explore how to be more thoughtful writers and more considerate readers in an environment that thrives on writing done in a moment.

Figure 1. A status update from BuzzFeed on September 24, 2015, after a Facebook outage.

The Update Not Posted

In the summer of 2015, I composed a Facebook status update about a fairly mundane occurrence in the life of a young parent. I had just coaxed my infant son to sleep when my dogs began barking at nothing. Naturally, the sound awakened my son, and it took another half an hour to get him back to sleep. As I stood perfectly still in his room, waiting to hear his steady, soft snores, I felt the need to express my outrage. I did what many of us do when we need an outlet for our raw emotional responses to life. I turned to the Internet. I typed out the status update on my smartphone: "Dogs barking at nothing waking up the baby = thoughts of dogicide."

Figure 2. Roch, a 10-year-old German pinscher

and an admittedly

photogenic

menace to naptime.

No dogs were harmed following the composition of that status update. I reread the status update draft and promptly deleted it, opting not to post the update to my Facebook timeline. And I began to wonder why. That moment became the source of this article.

Although I was pleased with my verbal play on homicide—sonically, dogicide seemed so much more satisfying than canicide, a word that for some undoubtedly horrific reason actually exists—I was not eager to display my brief spurt of parental rage and frustration. The notion of “dog murder” did not align with the digital identity I have sought to craft through sharing snippets of my life in the form of wry remarks, anecdotes about academic life, and photos of previously acknowledged dogs and children. Of course, I have undone my own efforts to curate my digital identity and conceal my outrage by choosing to publish about my writing in that moment.

I suspect that my Facebook friends would generally be sympathetic to how I felt in that moment of burning parental fury and would probably understand the need to share that frustration. But even though I anticipated understanding among my readers, I still deleted the update. I’m not afraid to share that I am an imperfect parent or that I feel the occasional impulse to violence, especially when I don’t actually act on that impulse. These are all aspects of being a human being. However, I chose not to share that moment because the anger in that moment was directed toward animals in my care, and I didn’t want to present myself as someone who would hurt dogs.

In general, I don’t aim for the most carefully curated, polished identity on social media. I find brief glimpses into people’s lives appealing, and I get to offer others glimpses into my life as well. Such displays of our everyday lives might satisfy our voyeuristic tendencies without leading us to become Jimmy Stewart, sitting in a wheelchair at our windows and watching the comings and goings of all of our neighbors. In fairness, his snooping did pay off in the end.

Figure 3. Jimmy Stewart in Alfred Hitchcock’s

Rear Window (1954).

Photo: Robert Burks.

As a social media user, I try to write with intention, to control the extreme edges of what I may put out there in the social spaces of the Internet, either in the relatively secure platforms like Facebook, the more public platforms like Twitter and WordPress, or even the ostensibly anonymous platforms like YikYak. I attempt to control the circulation of texts that define who I am, personally and professionally, in relation to the digital communities I participate in.

Of course, we do not control how texts circulate, especially in digital environments where text can be forwarded, reposted, and retweeted. The circulation of online texts is so rapid—the term “viral” refers not only to a significant number of people viewing a text but also to the astonishing speed with which that text spreads—that the moment we submit something online, it is out there, available to be viewed by others in our digital communities.

Navigating Self-Representation in Digital Communities

We have not yet advanced (or is it regressed?) to the level of Tron or The Matrix and abandoned our physical selves for digital environments, but those of us who engage in social media put a great deal of and about ourselves out there in the cloud. Social media users share writing, images, videos, and music to write the moment—to capture their present feelings and, through the composite act of sharing those bits over time, to construct their digital identities.

The immediacy of social media and the importance of display in its use makes social media a form of epideictic discourse, one of the three discourse types identified in Aristotelian rhetoric. I argue that framing social media as epideictic discourse encourages us to be more intentional writers and more sympathetic readers. When social media is used in intentional ways, individuals can exert more control over their digital identities. Framing social media as epideictic discourse helps to emphasize the importance of writing with intention, even if such control is not always possible.

Our understanding of what epideictic discourse is and what it does has evolved since Aristotle wrote about the three types of discourse: forensic, deliberative, and epideictic. Forensic discourse is characterized as speech connected to the past, generally associated with the legal process of making judgments about the guilt or innocence of individuals. Deliberative discourse is associated with political action, and is thus connected to the future. Epideictic discourse, however, is oriented toward the present because those who give ceremonial speeches “praise or blame in view of the state of things existing at the time” (I.3.18-19).

Social media is epideictic not only because of its powerful emphasis on the present and on display—what could be a better example of discourse focused on the present than a photo of someone’s meal or a beautiful cup of coffee (as in Figure 4) uploaded to Instagram?—but also because it provides space for people to praise or blame others and, most importantly, because it enables individuals to create and participate in multiple communities.

Figure 4. Coffee Porn. Photo: Jeremy Keith.

If we look at social media as a type of epideictic discourse that frames digital identity in relation to different digital communities, then we must ask: Who controls that identity? Do those of us who use social media have full control of our own identities?

Of course not. Identity is ultimately a socially constructed concept; someone’s identity is built from fragments and shards of their personal preferences, their experiences, and their interactions with others. So while we may desire to control our digital identities through the epideictic act of displaying particular aspects of our lives, the very nature of digital networking means that individuals cannot control every aspect of how they interact with others, nor can they control what others may say about them in digital spaces.

For an example of how epideictic discourse shapes digital identity, let’s take a look at the recent controversy surrounding the case of Minnesota dentist and largely reviled hunter Walter Palmer.

The Lion, The Dentist, and the Internet

In July 2015, reports of the killing of Cecil, a lion in Zimbabwe, flooded the Internet. Shortly thereafter, Palmer was revealed to have killed Cecil, having paid others to lure Cecil off of protected land.

Figure 5. Cecil the Lion in Hwange National Park in 2010.

Photo: Wikipedia.

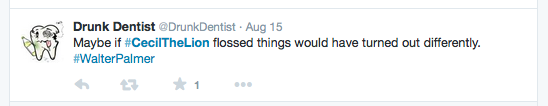

The social media response was, and this is a real understatement, intense. Atlantic writer James Hamblin characterized responses on the Internet as an “outrage singularity,” a “perfect storm” of condemnation and hatred from Internet users. On Twitter, #CeciltheLion trended as outraged users first lamented the lion’s death, then assaulted, parodied (as seen in Figure 6 and later in Figure 10), or defended Palmer, and then attempted to demonstrate that some outrages are more important than others (as seen in Figure 7).

Figure 6. A tweet from Drunk Dentist on August 15, 2015.

Figure 7. A tweet from UnbornLivesMatter on August 14, 2015.

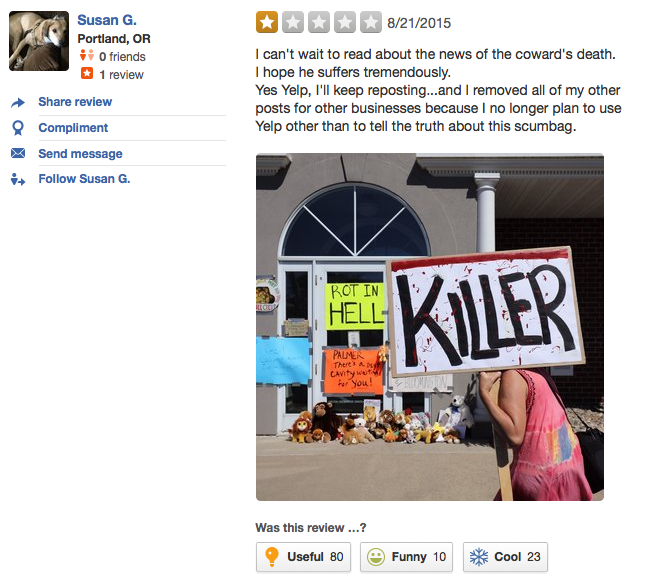

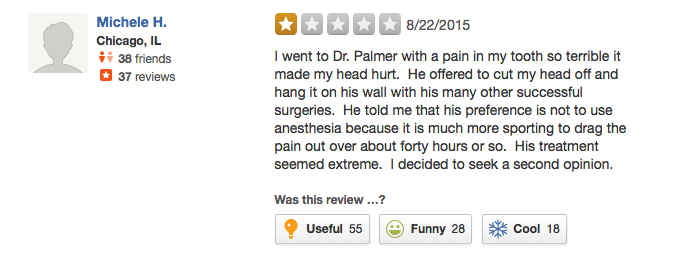

On Yelp, a site consumers use to review businesses, users bombarded Palmer’s dental practice with negative feedback. The posts range from calling for Palmer’s death, as in the first example below, to parodying Yelp’s original purpose to criticize Palmer, as in the second example.

Figure 8. Yelp review of Palmer’s dental practice, posted on August 21, 2015.

Figure 9. Another Yelp review, posted on August 22, 2015.

In both cases, the rating system for the reviews indicate that others viewing these posts found them “Useful”—roughly a “Like” equivalent for Yelp—indicating how intensely people want to harm Palmer’s reputation. Walter Palmer’s digital identity has been destroyed through social media, and that damage will have a long-term material impact on the despised dentist. It is too soon to know how permanent an impact social media has had on his practice, but at the very least, Palmer will spend a significant amount of time, and probably money, rebuilding his reputation within his local community.

Someone’s digital reputation can be influenced by what the person posts or by what others post about them, but either way, how one is portrayed online contributes to their digital identity. In the broader digital communities, Walter Palmer’s reputation is likely unalterable at this point. He could employ a company such as reputation.com, a business that works to wipe a person’s digital identity clean and give them a clean start. (For more on the business of reputation, listen to “Silence and Respect,” an episode of Reply All, a really worthwhile podcast about Internet culture.) But the outrage surrounding Palmer’s actions was so intense that such rehabilitative efforts would likely prove ineffective.

What the example of Walter Palmer demonstrates is that social media can have a profound impact on an individual’s personal and professional life, even if that individual isn’t the one actually using social media.

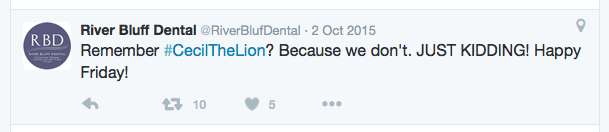

Additionally, social media provides a means in some cases for others to hijack digital identity, which can negatively contribute to the construction of digital identity. Note this tweet, ostensibly from River Buff Dental, Palmer’s practice in Minnesota:

Figure 10. A tweet from RiverBlufDental on October 2, 2015.

A quick perusal of this Twitter handle’s previous tweets offers a plethora of photos of lions in comical circumstances that would never help to rehabilitate Walter Palmer’s digital identity. And unlike the Drunk Dentist Twitter handle from Figure 7, the River Bluff Dental handle appears genuine at first glance, employing the logo from Palmer’s business to imply that this is the official voice of Palmer’s dental practice, but it isn’t. It’s a parody account.

The example of Walter Palmer offers an example not only of how individuals can influence the digital identities of others but also how those same individuals are constructing their own digital identities by posting about someone like Walter Palmer. For instance, UnbornLivesMatter’s tweet in Figure 7 demonstrates how people can use moments of Internet outrage to attempt to redirect attention in other directions. But social media also has the capacity to blur lines between parts of our identities that we typically want to keep distinct. Or indeed, how we use social media may simply acknowledge more fully our digital identities than other forms of digital communication can do.

Writing with Intention and Reading with Empathy

To assert that we are in control of how anything circulates online is difficult to defend, what with invasive technologies that observe and record our behaviors, the ability of viewers to capture screen shots of tweets or status updates no matter how fast we try to delete them, and the human capacity for interpreting words and images differently than we intended.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t seek to write with intention—to contain some of the edges of our thoughts, like wanting to murder our dogs. After all, what we write in social media can have very real consequences. For example, recall Justine Sacco, who in 2013 tweeted, “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” The Public Relations representative for InterActive Corp was fired for the tweet.

But most of us do not face such extreme circumstances. Since most of us aren’t dentists who have killed beloved animals or executives who insult the populations of entire continents, our lives on social media are generally fairly banal. We share pictures of what we are eating, brief anecdotes about amusing things at home or work, or articles we find interesting. We live-tweet television shows and conference presentations or use status updates to generate to-do lists or set accountability goals. If you’re the parent of two young children like I am, you may be guilty of sharing too many photos of your children.

Or if you’re this guy, you may don a mask to make your ordinary suburban life extraordinary.

Figure 11. Tweet from BatDad on September 20, 2015.

Thinking about social media as epideictic discourse—as rhetoric that routinely constructs and displays small pieces of our digital identities—encourages individuals to consider the ramifications of what we share. We can be more aware of what we display for the world to see. The moment of consideration that determines whether or not my online friends will question whether I am a dog murderer or not is the moment when I decide how to display myself in my networked publics. It’s the moment when I write with intention.

But the flipside of writing with intention is reading with empathy. After all, we know how easy it can be to post something to Twitter or Facebook that we later regret. In the digital world, where so many individuals seek to express so many complex emotions and experiences in short status updates, tweets, and images, we could all stand to be more empathetic readers.

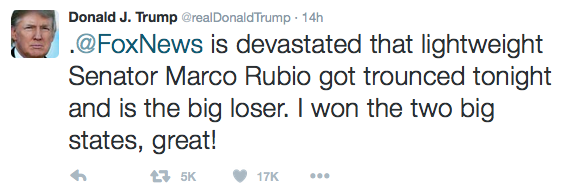

Reading with empathy doesn’t mean accepting what others say or allowing wrongs to go unaddressed. After all, we are currently living in a world where American politics looks like this:

Figure 12. A tweet from Republican presidential hopeful Donald J. Trump on March 6, 2016.

Reading with empathy means that we can and should take a moment or two to think before we respond on social media. Reading with empathy is the necessary precursor to writing with intention, and we need a good deal more of that as we move forward in this political climate.

The rise of social media has changed how we interact with others. We must all be more mindful of how we present ourselves in digital spaces, but we also must be more forgiving that people sometimes make missteps and commit faux pas in social media. At the least, we must pause and consider our responses to make sure that we are displaying ourselves as we would want to be displayed. We need to continue exploring how our digital identities interact with the networked publics we participate in, and framing social media as epideictic rhetoric can help us to do that.

As comedian Paul F. Tompkins reminds us, everything is digital now. Even you are.

References

Aristotle. The Rhetoric and the Poetics of Aristotle. Trans. Rhys Roberts. New York: Modern Library, 1984. Print.

boyd, danah. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. New Haven: Yale UP, 2014. Print.

Chase, J. Richard. “The Classical Conception of Epideictic.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 47 (1961): 293-300. Print.

Consigny, Scott. “Gorgias’s Use of the Epideictic.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 25 (1992): 281-92. Print.

Duffy, Bernard K. “The Platonic Functions of Epideictic Rhetoric.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 16 (1983): 79-93. Print.

Hamblin, James. “My Outrage is Better than Your Outrage.” Atlantic. 31 Jul. 2015. TheAtlantic.com. Web. 9 Oct. 2015.

Harpine, William F. “Epideictic and Ethos in the Armana Letters: The Witholding of Argument.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 28.1 (1998): 81-98. Print.

Perelman, Chaim and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca. The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Trans. John Wilkinson and Purcell Weaver. Notre Dame: U of Notre Dame P, 1969. Print.

Sullivan, Dale L. “A Closer Look at Education as Epideictic Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 23 (1993): 70-89. Print.

Jacob Babb is Assistant Professor of English at Indiana Universtiy Southeast. He publishes on composition theory, writing program administration, and rhetoric. He teaches courses in writing, rhetoric, and science fiction. He is pleased to report that he has still not committed canicide and doesn't plan to in the future—not that he would publish his plans to do so here.