Bits and Pieces: A Sculptor's Reflection on Meaning

Christina West

This piece is a reflection on intention and meaning in my figurative sculptural installations. Examples from specific pieces illuminate my decision-making process.

“A story that is any good can’t be reduced, it can only be expanded. A story is good when you continue to see more and more in it, and when it continues to escape you,” declared Flannery O’Connor, a writer close to my heart (102). She also has written, “People have the habit of saying, ‘What is the theme of your story?’ and they expect you to give them a statement . . . and when they’ve got a statement like that, they go off happy and feel it is not longer necessary to read the story . . . but for the fiction writer himself the whole story is the meaning because it is an experience, not an abstraction” (73). If she were alive, I’d want to be her friend. And when she’d make such statements, we’d give each other that knowing head nod and then bump fists.

Speaking, writing, communicating about my work doesn’t necessarily have to translate to a reduction of it to words or abstract ideas.

O’Connor speaks specifically about writing, since that is what she knows best, but as a sculptor making work that flirts with narrative, I find it easy to look beyond the boundaries of medium and embrace her thoughts. So, hell yeah, Ms. O’Connor: I too think of my work as an experience that’s impossible to reduce to an explanation — impossible because the visual and verbal, spatial and cerebral, imaginative and empirical are inextricably linked and are at play within the experience of the work.

But the dilemma that quickly surfaces about work that “can’t be reduced” is: how do I talk about it? (And oh, do I ever have to talk about it! I was the shy kid who wouldn’t say a word in public unless bribed, and now it’s common for me to give public lectures about my work. Thank god I’m pretty good at picturing people in their underwear, or whatever). I’ve decided that the best way to deal with this conundrum is to adjust my attitude: speaking, writing, communicating about my work doesn’t necessarily have to translate to a reduction of it to words or abstract ideas. Rather, I try to think of it as a way of giving people entry into the work, a way of providing some orientation that allows viewers to access the complexity or layers of meaning that are potentially there. I hesitate to talk about meaning in the work as an equation — “this means this” — and instead find it useful to simply discuss my thought process. How do I make decisions about things such as imagery, color, scale, placement in the gallery? Together, these elements create the content of the work.

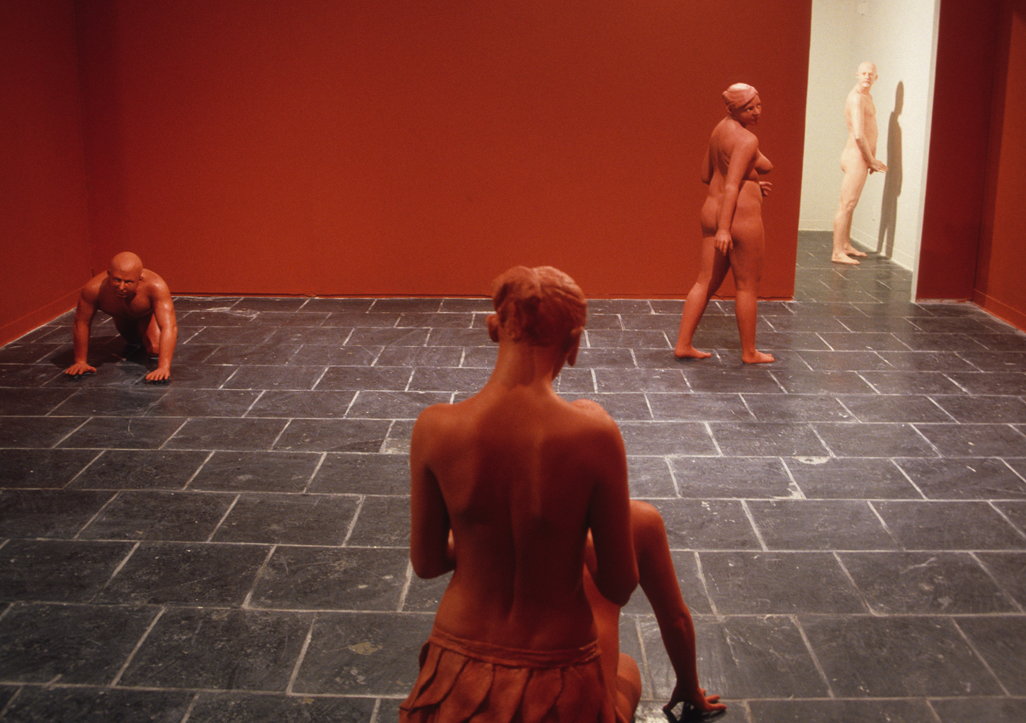

Figure 1

The accompanying images illustrate the installation format that is common to my work. Multiple large-scale sculptural figures are strategically grouped in a gallery space. A suspended moment is presented sculpturally — a moment freed from the context of previous moments or common mythology. The figures rely on proximity to each other and their placement within the gallery space to generate inklings of narrative and encourage audiences’ projections about the nature of the fictional situation. There is no single narrative to be gathered from the work, but a few potential stories dependent on how individuals respond to the imagery.

It is common for people to ask me “What is he doing?” or “What is going on here?” when looking at my work. And then they glance at me suspiciously when I say that I’m not sure.

For example, in the untitled sculpture of the two gray-colored women (Figure 1), the relationship between the women is uncertain. Responses to the piece range from people thinking that the interaction between the two figures is playful, or spiteful, or sexual. In my mind, none and all of those responses are “correct.” I consider a piece successful if it has the ability to oscillate among a few responses while remaining a nagging question in the audience’s mind. It is common for people to ask me “What is he doing?” or “What is going on here?” when looking at my work. And then they glance at me suspiciously when I say that I’m not sure. But truthfully, I choose poses exactly for their potential to circumvent such narrative clarity or conclusion.

For me, this ambiguity mimics reality, with its layers of uncertainty and mystery shrouding the psychology, or interiority, of those we encounter; as many clues as the body may give through its language, we never can know with certainty the inner workings of those around us. (This is reinforced every time I find myself thinking about the aesthetic and conceptual possibilities of play dough during a faculty meeting. If I’m thinking about play dough while we’re voting on unexploited opportunities in the university, what could my colleagues be thinking about as they smile and nod?)

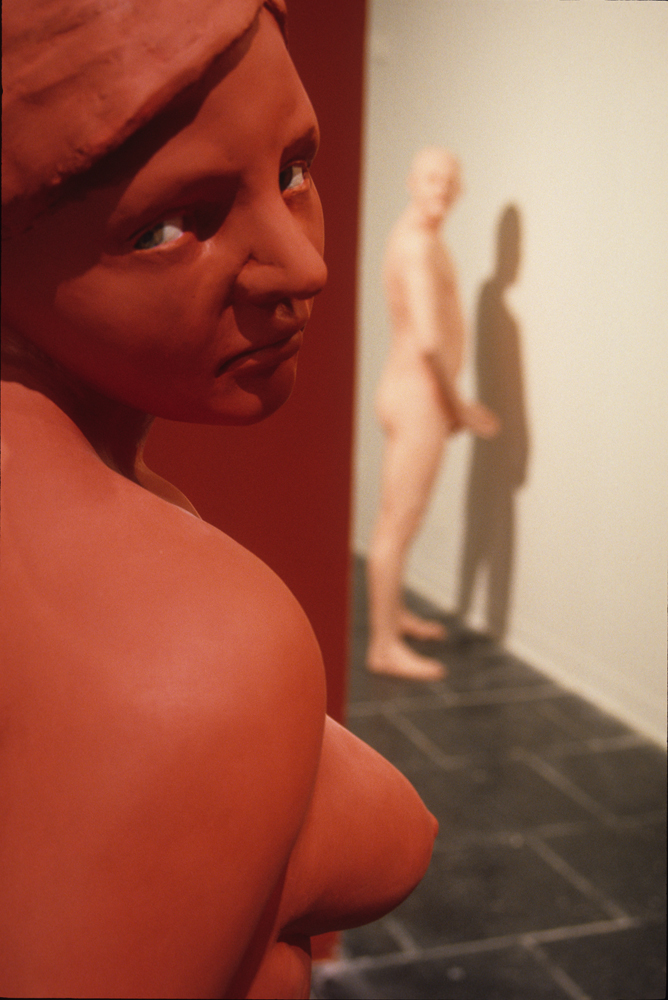

Figure 2

Each figure is the result of numerous formal decisions: amount of clothing, degree of realism, body type. Ultimately the representation of each figure contributes to the piece as a whole. In this piece, titled Red, the initial view upon entering the gallery reveals the backside of a naked male figure standing close to the back wall (Figure 2):

His hands and the front of his body are out of view as he intently peers to his right through a doorway. His lack of clothing functions as an instant hook. Regardless of assumptions that art spaces are governed by different conventions and codes of conduct than most other public spaces, unclad bodies successfully pique the curiosity of the voyeur within most of us. (Admit it, we all want to peek at the “bits,” don’t we?)

Figure 3

The degree of realism with which his body is rendered enhances the effect of his nakedness because it makes it easier to suspend disbelief and see him, momentarily, as a palpable human presence. The type of body represented is equally important because it contributes to the tone of the piece. His body is rather ordinary . . . not handsome, but not ugly either; not muscular, but not overweight; his head is a little small, and his butt is a little large. He’d more likely be a character out of Of Mice and Men than the Iliad.

All of the figures in the installation, because of their rendered realism and specificity, are immediately recognizable images. They are sculptural objects that can be readily identified and described, creating an expectation of transparence or clarity. I purposely strive for such expectation because it becomes an effective foil for the lack of narrative clarity or conclusion: Anticipation highlights its absence.

When planning Red, I also considered how the piece would unfold as people moved through the gallery space. The wall to the right of the pink male figure — the wall with the doorway cut out of it — was my addition to the gallery space. This additional wall bisects the gallery into two rooms, allowing for the minimal initial view previously discussed. I desired the remaining figures to be concealed behind the wall as people entered the gallery space so that the piece would reveal itself more slowly. When first entering the space and only seeing the male figure looking through the doorway, one wonders what is in that other room. It becomes a question, a source of anticipation and suspense. One first approaches the male figure to see exactly what he’s up to (“Is he doing what I think he’s doing?”), and then enters the second room to see what has captured his attention.

Figure 4

This new room presents a jolt of color — the walls and all of the figures within it are entirely red — as well as a surge of implied activity since the remaining four figures are found there. A female sculpture, in a gesture of walking, is confronted at the doorway into the red room. Her immediate proximity to the personal space of viewers as they walk through the doorway contributes to the sense of intensity and urgency in this room. Such decisions about color and placement create a discernable and abrupt shift from the tone and cadence of the initial room.

Figure 5

In addition to potential emotive content, I think of color within the gallery space as a framing device; painting the gallery walls the same color as the figures is a gimmick common to my work. The figures are obviously art objects — and by association, anything in proximity to and displaying similar qualities as those objects is also considered art. So simply by adding a specific color to the walls, the gallery is appropriated into the fictional world of the figures. This helps give the figures visual and narrative cohesion even when there is a great deal of space between them. The whole room becomes the piece and people walk directly into the space, navigating around the figures and among the suspended narrative. The sense that the viewer is an intruder, or “other,” is highlighted in such a context, which is evident in photographs of the work that include images of viewers for scale reference. These images always seem more surreal because the work is juxtaposed with “reality” to a startling effect.

Figure 6

Color isn’t the only factor contributing to the surreal quality of the work. Scale is at work here as well. Typically about ¾ life-size scale, the figures are large enough to have a presence in the gallery comparable to that of another person but also small enough for it to seem odd that they are rendered as adults. Even my shortest friends tower over them. Viewers inevitably bend and squat to get a good look at the faces and inspect nuances of the bodies (a privilege unfortunately deemed offensive in most other situations). Larger work can seem confrontational as it towers over its audience, but this scale literally pulls people into the work. They can be right up in the figure’s business and still be able to take in the image as a whole.

Figure 7

But of course, all of this supposes that people come in contact with the work. Most people don’t have the chance to see my installments in person and, consequently, don’t get first-hand experience of the scale and spatial relationships that are so important to it. This is true for most visual art, actually. And that’s why articles like this, though they cannot replace the experience of encountering the work in person, are necessary and valuable. O’Connor would tell people to just go read her stories. I’d like to do the same — to urge people to just get to the gallery — and ideally, this reflection makes that an enticing invitation.

References

O’Connor, Flannery. Mystery and Manners. Eds. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1961.

Christina West is an assistant professor of art at Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA. Visit Christina’s website: http://www.cwestsculpture.com.