Clothes Make the Lesbian

by Carrie Kosicki

Lots of gay women wear dresses. It became pretty clear early in life that I'm not one of them. The earliest incarnation of this essay was born of an assignment for a class I took six years ago. The prompt: Write an essay about the first time you were aware of your sexuality. The result: After some soul searching and some digging through family photo albums, I had to wonder why it took me as long as it did to figure things out. Clothes don't necessarily tell us much about a person, but they can. I freely admit that they can tell you a thing or two about me.

Mr. Wolfe’s voice rose like a slide whistle, climbing two octaves after he reported the previous evening’s football score and transitioned into the next announcement: “Now something for our newest students. The seventh-grade autumn dance is scheduled for one week from tonight,” he said. “And now, please rise while we recite the Pledge of Allegiance.”

Invitation

As I stood there with my hand over my heart, I flashed back to three weeks earlier when I was still a sixth grader playing touch football in the middle of the street with the boys in the neighborhood. Even then I had some notion that there would be dances in my future, but in my child’s mind, it had been the kind of hazy future that I associated with getting a job or moving out of my mom’s house. Now, sitting in a new school with a new pool of students, most of whom knew nothing about my twelve years of grass stains and softball trophies, I could clearly see that future. I could picture the first kisses I’d seen acted out by characters about my age on my favorite television shows and the cases of makeup that my older cousin was always trying to get me to play with, and I wasn’t ready.

The feeling of dread in my gut didn’t match the emotions I observed in the other girls around me as we retook our seats. While they wriggled around on the apparent brink of wetting themselves with excitement, I shrunk myself into as tight a ball as I could and tried not to throw up. No matter how much I wanted to be the kind of girl who looked forward to her first dance, I just couldn’t see myself going through with it.

That afternoon, when I got home from school, my mom rushed to meet me at the door. Without saying hello, she flashed a piece of paper in front of me. I barely had time to register the pirate emblem on my school’s official letterhead before my mom asked, “Do you want to go to this?” I grabbed the letter and skimmed it while my mom watched my face for some sort of reaction.

Without thinking I said, “Yeah, I’ll go,” and handed the notice back to her. My mother, like all mothers, is omniscient. After years of driving me to basketball practices and taking me to the toy store the day after Christmas so that I could return whatever Jem doll or My Little Pony my grandmother bought me in exchange for toy guns or He-Man figurines, “yeah, I’ll go,” was not the answer she expected. After a day of listening to my classmates talk about what they would wear and whom they would dance with, it wasn’t the answer I expected either. I attempted to explain away the confused look on my mom’s face. “If I don’t go to at least one, how will I know for sure that I don’t like them?” I’m not sure I convinced either of us.

"Misery, Thy Name is Dress"

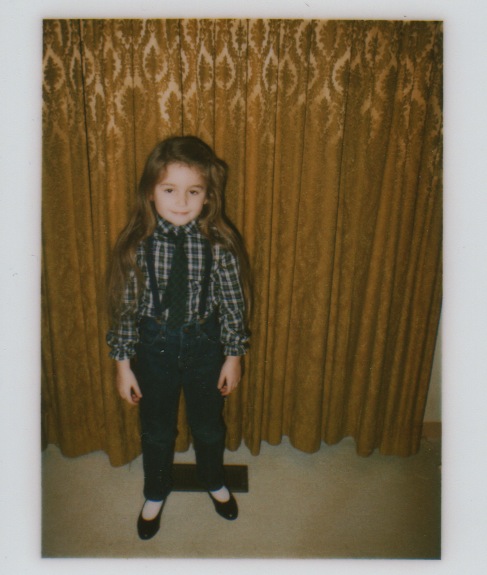

I was six and it was Easter. As was typically the case, my father recorded the event with the 35 mm camera that always hung around his neck. My mom still has the picture. In it, I’m standing with the Easter Bunny outside my grandparents’ country club where we were having brunch. I’m wearing a sleeveless pastel dress with a somewhat frilly, slightly puritanical white collar. My hair is long and pulled back in the same braid I wore it in every day of the year. Keeping my hair out of my eyes while biking through the woods or hunting in the creek for salamanders was the only sort of thing that informs my sense of style. My mother likely decided that letting me wear it back on this day was easier than getting me to submit to the amount of time it would take to brush through the tangled mess. My head is tilted down, but my eyes gaze up, not quite in the direction of the camera. I look uncomfortable, unhappy. Perhaps I feel like someone who’s being forced, against her will, to exist outside of her comfort zone. A girl who is trying, and failing, to pass herself off as someone she isn’t. Or maybe, as someone looking at the picture now and finding the scene wholly unnatural, I’m projecting.

In the days preceding the dance, I tried to talk myself into being excited but all I could think about was that picture of myself, costumed and miserable. Something happened during the transition from elementary school to junior high. Before, no one seemed to care that I never wore skirts or that I played on the boys’ basketball team. Now, everyone needed to fit into one neatly defined camp or the other. The grey area between boy and girl that I’d always found so comfortable no longer existed, and this dance felt like a time when I’d have to pick a side. I thought about the picture again and realized that this idea was why I was so nervous about the dance. What I would be expected to wear and what I would be comfortable wearing were two completely different things. I knew it and my mother knew it and as such, we did what we always did when we found ourselves in an uncomfortable situation: We avoided it until the last possible moment.

The day of the dance, my mom and I finally went to the mall. My mom seemed to be under the impression that implied within my decision to go to the dance was the simultaneous decision to present myself in a more traditionally feminine fashion. “Well, this is the sort of thing that the other girls are going to be wearing,” she said nervously, holding up a dress.

“Mom, I’m not wearing that crap,” I said. Taking my nerves out on my mother was the only way I could get through the situation.

“I’m just trying to help,” she said.

I turned away and headed for a friendlier section of the store, a section with separates and inseams. My mom followed without saying anything else. She must have known that the dress issue was a lost cause. Her suggesting it at all was surely some last attempt to save me from the judgmental stares of my classmates later that night. What my mom didn’t realize was that her holding up the dress that helped me make the decision I’d been putting off for two weeks. There was no way I could see myself in that thing or anything like it. It was pants or nothing.

"Harbinger of Things to Come"

Once the decision was made, the rest of our trip to the mall was easy, enjoyable even. It turned out I knew exactly what I wanted. I just had to tell myself it was okay to want it. I left with a pair of hunter green trousers, a green and white striped silk shirt, and the article of clothing about which I was most proud. Eastland boots were as ubiquitous as acne in my midwestern junior high school, and the occasion of my first dance was the perfect opportunity to talk my mom into buying me a pair. With my new outfit, my new boots, and nothing but the jeans-and-oversized-sweatshirt-clad image of myself that I was used to seeing in the mirror against which to compare myself, I felt naively confident in my appearance and excited about the dance for the first time since Mr. Wolfe made his announcement.

The sounds of the early ‘90s bounced off the concrete walls and crashed into my eardrums with a force that made my insides shake. The country stylings of Garth Brooks followed Boyz II Men’s R&B without the courtesy of a transitional buffer. The stench of cologne and pubescent sweat was so thick I could taste salt and rubbing alcohol every time I inhaled. There were streamers and balloons hung sparsely throughout the room, but the stickiness of the floor, left over from lunch that afternoon, served as a reminder that the room was still just a cafeteria.

As I looked around, I took a quick inventory of my classmates. The boys all looked the same in their black or tan pants, white collared shirts and clip-on ties. I remembered my father teaching me to tie a Windsor knot when I was in the third grade and the Saturday mornings when he would squeeze a dollop of shaving cream into my palm and hand me a razor with the protective cap still on so that we could shave together, and I felt superior to these boys in every way. Then I noticed the girls. They all fell into one of two categories. Some looked like they were dressed for a family portrait, all dark velvet and lacy collars. The others, wearing too-short skirts and dark, heavily applied lipstick, looked more like the kinds of women my grandmother had warned me about when she took me to New York City. “They’re prostitutes,” my grandmother had whispered. I wondered whether these seventh graders’ mothers had been as involved in their wardrobe selection as mine had. I pictured a girl’s mom in a department store holding up a sundress and asking for some sign of approval.

"Practice Makes Perfect"

“God, mom, do you want me to grow up to be a nun?” the girl would say as she stormed off in another direction. I hadn’t seen a little whores’ department in the store, but then again, I hadn’t been looking for one either.

I had been in the cafeteria-turned-dance-floor for a couple minutes but still hadn’t made eye contact with anyone, not because no one had looked my way, but because I hadn’t had the courage to look back. The moment I saw those girls, the prudes and the whores alike, any confidence that I had felt, the kind of confidence that only a girl like me could feel in that ridiculous outfit, was gone.

I leaned against the cafeteria wall so hard that an outline of the painted-over cinderblocks pressed its way into my skin. I looked out onto the dance floor, hoping at once to go completely unnoticed and that someone would come up and talk to me because no one sticks out quite as much as the girl all alone off to the side of a dance. “Hey, Carrie.”

I looked up, and Rachel Anderson was standing right next to me. Rachel looked much like you might imagine Jennifer Aniston would have looked at twelve. This must have been both a blessing and a curse for her since this was right about the time that the television show Friends was becoming popular. She had long, sandy hair with blond highlights, blue eyes, and she laughed at my jokes. “Hey, Rachel,” I said.

That’s the extent of what I remember of our conversation, and even that is probably not verbatim. What I can say is, seventeen years later, remembering that she came up to me at the dance still makes me smile a little.

When Rachel walked away, I fought the urge to follow her and instead pressed myself deeper into the wall. As I stood there watching my classmates, I continued doing the only thing that came naturally, the thing I’d been so afraid that everyone would do to me. I silently criticized all of them. I thought of 12-year-old girls as whores because they had the nerve to wear skirts that fell two scandalous inches above their knees. I attacked little boys’ masculinity because they couldn’t tie their own ties. Then there was Christie Jacobs. Christie Jacobs wore pants too, and though we did have some other things in common, we were on the same basketball and softball teams, Christie Jacobs also happened to be the loudest, most obnoxious person I had ever known. I didn’t care if everyone in that cafeteria thought I was a dyke so long as they didn’t think I was anything like her.

As the other seventh graders fumbled their ways through this early phase of growing up—the boys awkwardly placing their hands on their dance partners’ shoulders, trying to maintain eye contact, shifting weight from one foot to the other in time with the music; the girls wrapping their hands around the boys’ waists, following along, giggling nervously—I watched not willing or not ready to participate.

It was a few years before I was able to pinpoint what I had learned that night. I didn’t understand my feelings at the age of 12 any more than I did when I was 6 and I presented my friend Ryan’s babysitter with a hand-drawn picture of a fish in the hopes that she’d want to babysit me too, or any more than when I was ten and I rewound and re-watched again and again the nightclub scene in The Rocketeer where a 21-year-old Jennifer Connelly, with her thick black hair, sea green eyes, and bright red lipstick, looked into the camera and sang, it felt like, right to me. Then one day it all seemed so obvious. I was 16 and alone in my room. Quietly, so that only I could hear, I repeated the phrase, “I’m gay,” over and over until the sound of the words no longer frightened me.

Carrie Kosicki has one of those liberal arts degrees that's hard to put to good use. She occasionally blogs at http://www.carriekosicki.blogspot.com.

This work has some rights reserved under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License.