Sexual Disorientation

Anne Balay

Membership in the category of motherhood typically derives from sexual behavior; ironically, though, maternity excludes sexual expression, meaning that you get to be a mother by having sex, yet sex is anathema to mother-ness. As a lesbian, I make sexuality visible, thereby drawing attention to this paradox. Further, like any kids, my daughters negotiate sex, sexuality, and identity as part of their processes of growing up. In our queer family, everything is up for grabs, and the fun lies in seeing what someone will try next. This article tells stories about how that works and feels.

I used to wish for a lesbian daughter. Predictably, the joke’s on me.

In any group setting, you lose coolness points if you refuse to find teasing harmless, but in this context, being an adult and a mom carved out for me a space from which I could testify that words hurt, that they hurt me, and that I wanted them to stop.

My daughter Emma identifies with gay men. Not with lesbian women. She has always known she was a straight female. And she’s comfortable and confident with both these parts of her identity. But she likes gay men and wants to be included among their tribe. For Halloween, she dresses as a gay boy and poses romantically with another “gay” friend. She has all her friends and teachers call her Brian.

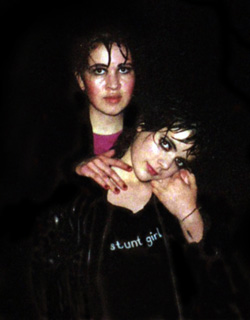

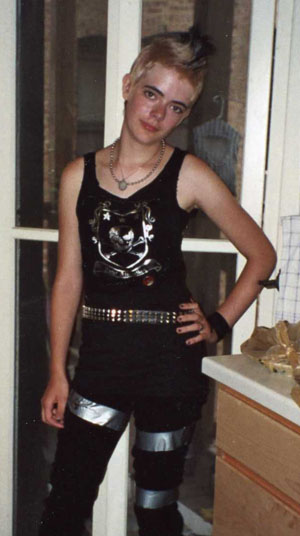

Often, teens try out new identities experimentally. Emma is experimenting with the gay male identity and does not feel that her body’s lack of conformity to certain parts of that identity poses a serious problem. She takes frequent “research” trips north to Chicago’s boystown neighborhood. She enjoys being with “her people,” testing how well she passes, and generally soaking up the vibe. The other day she and her flamboyant, 6’1” friend Hannah were returning by train from one of these trips uptown. Hannah wore a chiffon party dress, black 8” platform boots, and miscellaneous chains. She was made up, as usual, like a whore on crack. She was, not surprisingly, mistaken for a drag queen, and someone on the train propositioned her. I’m told her instant response was to look horrified and exclaim, “How could you say that in front of my boyfriend?” Emma, who was wearing tight corduroys and has 70s-style, feathered hair, does make a pretty convincing fag. There’s something about her bearing – the way she carries herself with confidence – combined with her thin-hipped, nearly breastless body and her pronounced eyebrows, that reads as masculine.

Recently, students in Emma’s 9th grade high school English class began to make anti-gay comments during class discussion, and the teacher either ignored them or laughed nervously. “Gay” or “that’s so gay” are ubiquitous insults in schools, and these students used that standby, as well as displaying mock horror at the vocabulary word homogeneous. Emma and several friends approached the teacher and expressed their outrage, and he agreed to attend to the issue. The students argued that these comments, while not explicit bullying, still make clear that gay people and perspectives are not welcome, and that by simply ignoring the comments, the teacher was contributing to that anti-queer atmosphere. Though the teacher agreed with them, the problem continued and Emma, who has a teensy tendency toward drama, alternately wept and raged about the injustice.

This all stopped when Leah delivered the line, “No. I do not look like a gay boy. I’ve been down Commercial Street in Provincetown, and I can tell you . . . .You look like a gay boy.”

I, then, found myself in the delicate position of approaching her teacher. Since Emma had tried to bring about change independently, I decided to contribute what adult authority I had to the problem. I am a lesbian and an English professor. Therefore, I have some feel for the delicate issue of policing class discussion, while encouraging speech and thought. But I work with college kids, who can be expected to navigate humor, sensitivity, and minority issues with some degree of grace. We can discuss stereotypes without employing them. We can assume that if someone is offended, they have the tools and the heart to say so. And we can discuss sex, desire, and fear without someone’s parent expressing moral outrage.

Identity politics assumes that people speak for and defend their own identity categories. Emma violates this norm in two ways: she defends identity categories not her own, and she believes identity categories are open and flexible. She – my daughter – has found herself by identifying with gay men. Not because she has or wants a penis which she would then use (or hope to use) in particular sexual practices. Not because she is “culturally” or stereotypically gay, but simply because that’s who she feels that she is. Her generation (at least parts of it) experiences gender identity as no more nor less than a game of dress-up, and she wants the rest of the world to accept this outlook as well. Instead, the teacher assumes that Emma is not straight, or that she’s questioning her gender assignment in some way. Emma doesn’t want to become male and thus gay because, to her, she already is gay. Her teacher couldn’t fathom that Emma identifies with gay without identifying as gay (i.e., non-straight), so he concluded that Emma was hiding something from me, or that I was shielding her secret from him. That I denied this, he took for protectiveness, or closeting, or naïveté.

I sat talking to this teacher for hours, as the only visible embodiment of a silenced gay minority. Numerous gay and lesbian people attend or teach at this school, yet if you’re not looking for them – if you don’t have the experience that makes them visible – you could easily miss it. I tried to convince him that girls named Brian are not gay, but other invisible people probably are. That I am. That nothing is certain. In any group setting, you lose coolness points if you refuse to find teasing harmless, but in this context, being an adult and a mom carved out for me a space from which I could testify that words hurt, that they hurt me, and that I wanted them to stop. My role here was to sit in the presence of this teacher and say that. Because sometimes you need to see a body before you believe what you already know.

Being a lesbian raising two daughters has been a series of such adventures. My sexual identity is inseparable from my maternal one. My daughters’ emerging identities is informed by my process of self-discovery. To some extent, this delicious, symbiotic nightmare is shared by all parents and children. But the circumstances of being a sexual minority in a culture that despises you makes sex more visible and draws attention to the fluidity of identity. Each member of a family unit, however constituted, then takes responsibility for their own experience as they come to understand that of other family members.

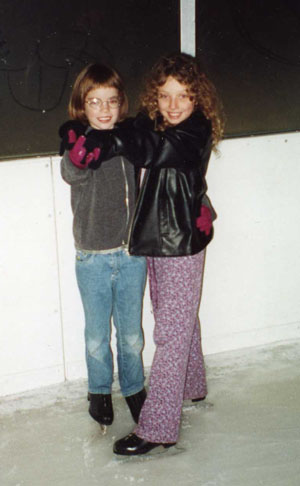

My younger daughter Leah made a new friend in second grade. Leah had short hair that she was in the process of growing out. It was still short in the front and sides, longer in the back – kind of mullet-ish, to be honest. I once overheard a conversation that began with her new friend Tenaya telling Leah that she looked like a gay boy. This comment sounded less like a flip insult and more like an exploration--as though she was testing what would happen if she said these words. Leah denied her allegation, Tenaya persisted, and the conversation went back and forth in that timeless, inane seven-year-old pattern. This all stopped when Leah delivered the line, “No. I do not look like a gay boy. I’ve been down Commercial Street in Provincetown, and I can tell you . . . .You look like a gay boy.”

And Leah was right. Tenaya then had long, blonde, frizzy curls with bangs that stood somehow up and out. To informed eyes, she resembled nothing as much as the queens scootering up and down Commercial Street promoting their drag shows.

Both my daughters have been “in the life” for so long that it seems somehow invisible and natural to them. They were 1 and 3 when I came out to myself, 2 and 4 when I went public. They’ve been to countless pride parades, attended gay and lesbian family weeks, and shared their lives with my numerous friends and lovers (and, as any experienced lesbian knows, the line between these categories is fragile and fleeting).

Before 9th grade English, there were very few instances where this caused trouble. We live in Hyde Park – an academic enclave within a liberal city within a very blue state. Words of acceptance, mouthed even if not always meant, are standard. And advocacy and community often go much deeper than that.

At one parent-teacher conference, I was sitting outside Emma’s classroom, chatting up another mom who I thought might be gay, and who I knew was fabulous. Rumor had it that the 3rd grade teacher we were waiting to see was gay, and he certainly looked the part. His gestures and diction had a slight campy edge to them – nothing you could put your finger on – just a little excess. But grammar school teachers, especially male ones, often avoid explicit self-identification, worried that it would make their work life uncomfortable, or even non-existent. When this teacher finished with his current parent, he checked his list, and announced it was my turn. Seeing Kristina sitting there with me, he said she should come in too and, naturally, she obliged. After our chat, he turned to her and asked if she wanted to add anything. Even as she identified herself as the next parent on the list, we all laughed, knowing that we had just fingered each other as members of a semi-visible tribe. If each one of us were not queer, we would not have understood his error. His assumption that we were a couple identified him as the type of person who might see couples like us as opposed to friends like us, even as it identified us as the type of people who might belong to this tribe. Because we were not confused, his words meant so much more than they said. Unplanned and mutual, this was a fun outing.

Unlike this teacher’s, my job is a comparatively easy place to be out. First of all, I’m a university professor, so I work independently and autonomously in classrooms where my only contacts are with people over whom I wield ultimate and arbitrary power. Of course, I don’t use this situation to punish bigots. Instead, I try to make my classes safe spaces to be gay, while also giving students opportunities to air, and ideally critique, their preconceived prejudices. Consequently, I tell who I want to tell, which amounts to all of my colleagues and about half of my classes. Some groups I don’t feel close to, or it just never comes up.

Ironically, that’s the same justification that Emma’s 9th grade teacher used for not explicitly raising the issue of homophobia in his classroom. He argued that if the topic grew out of readings or discussions of them that the class had shared, then he would address it, but without that connection, the conversation felt artificial to him. He argued that responding to tangential banter might legitimize rather than silence it.

Makes sense. At the same time, it seems to me that he (and the school system in general) has selected a curriculum in which that issue never appears. Not even close. Therefore, the conversation will never happen unless it’s raised artificially. The teacher seemed to accept this point, and asked me what I wanted him to do. My reply was that he needed to discuss the situation explicitly in class. I hoped he would explain that a hostile climate, even if humor supposedly renders it harmless, makes queer students feel unwelcome, even exorable. Thus, I hoped he would say the words gay and lesbian in class and even announce that there were probably gay and lesbian students present who were remaining silent for their own safety and sanity. These students deserved the same care and respect granted to other minorities. At a minimum, I suggested he might say the words gay and lesbian, thereby turning the classroom into a space where these were descriptive terms, and not insults – words that named reality.

The following day, I took Emma on a shopping trip. Unregenerate American that I am, I saw this as a prime way to get and hold her attention. My goal was to get her to see how hard this conversation would be for him, and thereby to lower her expectations for classroom transformation. Small steps come before big step, and impatience is unproductive.

And indeed, Emma seems satisfied. She announced that it was sweet to see him try. The word he chose to say was homosexual. This choice of clinical, rather than human language reflects the teacher’s discomfort with the topic, but he did personalize the conversation by telling the class that he had been discouraged from writing his master’s thesis on Oscar Wilde because of the notorious obscenity trial. Did he explain to the students that his advisor probably thought he might be found “guilty by association,” and therefore unemployable? Did he describe the process whereby boys learn to reject and despise the feminine in order to achieve unchallenged access to male privilege? Did he?

I’m guessing not, but he didn’t have to. He just had to accept that a female student named Brian, who is not a lesbian, needed to believe in a safe and noble world. A world where she, and everyone else, can love whoever they chose, and be whatever they want – a world of sexual disorientation.

And inevitably Emma is in love. As I imagine this boy being romanced by a very self-assured and assertive, absolutely gorgeous, long-limbed, sapphire-eyed and brilliant freshman he knows only as Brian, I feel new hope for gender justice in this world. Just don’t ask me who the gay boys are.

Anne Balay is an Assistant Professor of English at Indiana University Northwest, where she teaches children's literature, American literature, and gender studies. She is writing a book about gay and lesbian steelworkers.