Moms and Teen Daughters:

Make Room for the Internet

Jaqueline McLeod Rogers

In several short decades, computers have moved into the heart of our homes and lives. As mom to two older teenage girls, I have been intrigued by the question of how mother-daughter relationships have changed because of relentless internet connection. To begin answering this, I combined my experiences with responses provided by four other mother-daughter pairs. What surprised me most? Moms of my generation believe we are closer to our daughters than we were as teens to our own mothers, yet our daughters unsettle this by choosing anyone-but-mom as confidante. Not that they are internet addicted — they value friends, books, and TV as other windows on the world. Together in using technology more and more, mothers and daughters are growing resilient cyborg skins.

Contents

PART I

Examining the Mother-Daughter-Machine Triangle

PART II

Our Daughters:

Virtual Information, Actual Advice, and Mom for Money

PART III

My Generation:

Lost in the Nuclear Family

Ourselves:

Leaving Home to Learn about Life

Moms:

Remembering and Forgetting Growing Up

PART IV

Being Cyborg Together:

“We’re inside what we make

and it’s inside us”

PART 1

Technology: Moving in Closer

I don’t recall exactly when my family got our first big black and white TV — it was always just hugely there in the living room from the early 60s on. Likewise, I remember always having a family phone, but back then we had only one in the house, a fixture in the kitchen, black, with a circular dial for making calls. Like many families, we had rules to prevent any of us three daughters from “hogging” either device, but this didn’t prevent squabbling about getting more time. In my teen years in the early 1970s, we were well into what Marshall McLuhan called “the electric age.” Although there was a youth movement calling for a return to simpler more natural ways — with Joni Mitchell recommending we “get ourselves back to the garden” (“Woodstock”) and Neil Young protesting the plight of “mother nature on the run in the 1970’s” (“After the Goldrush”) — most of us remained thoughtlessly dependent on television and phones for entertainment and to connect us to the world outside our homes.

When home computers became popular household items (really not too long ago — around the mid 1980s), they were, like the first televisions, huge in size. A computer was often given a room of its own, named for it — “the computer room” — and designated solely for its use. Incrementally, year-by-year, the computer has become smaller and more mobile. No longer a lumbering box in a home-office, it moves from room to room in laptop or cell form, or takes up residence in the kitchen as part of a sleek built-in countertop. These changes, making the computer more accessible throughout our living space, raise the question of whether this machine has become a sort of “cy-mom” in many suburban homes — a smart machine, always at hand to provide information and advice that, unlike mom’s, comes free of judgment or unwanted followup.

For those of us who are parents of teens and young adults, the history of how the computer moved in with us is still easy to recall, but for many of our children, currency trumps history. Sometimes called “digital natives” for being the first generation to have grown up with computers, teens and young adults find it hard to imagine homes without computers and internet connections. Many of them struggle to remember a time before laptops. Yet even if my sense of history may be sharper than my teen daughters’, increasingly I have noticed myself becoming more like them in being a daily internet user and with this increased use more habituated to and non-critical of the computer. Also keeping apace with my greater reliance on the internet has been my decreasing commitment to regulating the hours my daughters spend on their computers. I seldom see them away from a glowing computer screen, yet it has been a long time since we have discussed regulations to govern either how much time they spend on the computer or how this time is used. They roam free in virtual space.

Of course, when they were younger, I kept a closer eye on where they went. It was when they entered their teens that I adopted the policy of trusting their judgment. Yet a question that begs to be answered is whether my new stance was based solely on their increased maturity or whether it developed equally from my non-critical adoption of computer technology into the home. When I was growing up as a teen, I remember frequently debating with my mother the rules she had set limiting television viewing and phone conversations. If my experience is common, it suggests that in the space of one generation we have abandoned parental vigilance in the face of information and communication technologies. Such non-intervention contradicts not only how we were raised but also the advice of regulatory bodies like schools and police, who remain on record recommending parental involvement. During the course of writing this paper, for example, one of my daughters brought home a flyer from school reminding parents about internet predators, and on a recent trip to the local police station to report a traffic mishap, I noted posters plastering the walls warning young and old alike of internet dangers. My point here is not that we should replicate our parents’ practices nor be guided by surveillance-oriented social agencies but that, rather than glibly accept computer intimacy, we need instead to reflect on how swiftly the computer has literally moved into the center of our homes as well as on how its presence may be affecting our lives and relationships.

Examining the Mother-Daughter-Machine Triangle

In Growing Up Digital, Don Tapscott argues that the computer has improved family dynamics by democratizing relationships. While there has been a loosening of parental authority, children have increased their domestic power because they have out-mastered their parents in the area of computer skills, which have intergenerational value (223). Whereas the current generation of parents were raised by authoritarian parents enforcing rules, Tapscott claims our children are used to participating in setting household standards.

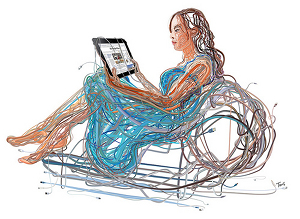

"Working on a computer in a leaning world" by patricio villarroel

Always On: the Computer as Competing Window on the World.

Apart from democratizing family relations, the computer — and more particularly, internet access — may have influenced family dynamics in other ways. As a mother of two older teen girls (ages 16 and 19 as I revise this study for publication, but somewhat younger when I researched it), I have had a stake in observing how the mother-daughter bond might be affected by the growing presence of computers in the home. While mothers and daughters both use the internet, our daughters as digital natives have never lived without computers, making them both adept and dependent as users. With answers to so many questions a mere Google away, have our teen daughters outworn our sagacity? Do most mothers, like me, allow teen daughters unlimited computer use, without pointing out that there is an “off” button? Have we simply been outsourced, and forced to accept that in our family dramas “the role of mom will now be played by Google and other social network options”? Do our daughters prefer consulting the internet rather than asking for our human point of view? Do they ever worry about getting inaccurate or limited information? Do mothers and daughters share the belief that the computer knows best?

To explore questions like these, I decided to interview four mother and daughter pairs, selected on the basis of resembling myself and daughters on such key socio-economic markers as age, race, and class. The age of the mothers ranged from late 40s to early 50s and the daughters from 16 to 20. All were white and mother–daughter pairs who lived together in suburban middle-class settings with the financial means to support the early adoption of new technology. I chose pairs whose circumstances resembled mine to see which of my experiences were shared and to initiate the process of triangulating my interpretations. While the responses of this small sample are not definitive, the comments I have recorded are bound to resonate with mother-daughter pairs outside of the study.

One of my key interests was to find out if there have been cross-generational changes to the way daughters look to mothers for advice and information. I asked the four women of my age group to remember their experiences growing up and their relationship with their mothers. I asked them to compare their lives as teens to the lives their daughters lead. In turn, I asked the teen girls to describe the process they followed as part of finding information and advice and to characterize their relationships with their mothers. I interviewed participants individually so that mothers and daughters did not overhear each other. I spent several hours talking to each individual to elicit a narrative account rather than an imposing question-and-answer format. I wanted participants to be able to make some spontaneous connections.

Despite asking open questions, I was aware of going into the study with expectations about the stories I would hear from mothers and daughters. I had found theoretical support for some of my expectations in the work of feminist-mothering theorist Andrea O’Reilly, who has made the case for the Demeter-Persephone myth being central to the story of mothering and mother-daughter bonding (456). It is often read as a story of a daughter’s coming of age and a mother’s grief in the face of aging and loss. In the myth, underworld god Hades steals Persephone away to his dark realm of sex and death, where she spends at least half of each year lost to her mother, who laments her loss and awaits her return. If it is true that this myth is resonant in mother-daughter relations, I expected some of the mothers might recast the myth in digital times to depict the internet as a modern-day Hades figure. Because the internet has moved so swiftly into the heart of our homes and lives — always at hand, always the object of our gaze — I expected the Persephone story would play out in the way some of the moms described the internet as a force detracting from the mother-daughter bond — pulling daughter from mother, an interloper, even a dark and threatening presence to the extent that it has the potential to make illicit connections.

And if I expected the mothers might characterize the internet as usurper, I also expected the daughters might express some concern about being over-invested in virtual life and missing out on practical experience. I thought they might draw on mythic elements by associating their commitment to virtual life worlds with Hades-like possession in an underworld and perhaps express some resentment toward the computer for possessing their attention and preventing them from participating more fully in life.

When I was preparing to interview the teen girls, a radio review of a newly published book Good to Go: A Practical Guide to Adulthood (Mckay and Zarzour) further fueled my assumption that teen and young adult women might feel that the computer had robbed them of real life experience or failed to prepare them adequately for its challenges. The authors claimed that contemporary youth are internet savvy but have made this gain at the cost of practical experience in real world activities: Many young people are unable to write a check, cook lasagna, do a load of laundry. To help young people live, the authors were offering to provide “Mom in a book” as a necessary antidote (Penguin).

"Persephone in Blue" by Temari 09

Computer as dark force, steal(steel)ing daughters,

locking them away from real life.

As my presentation of the responses will indicate, these patterns did not play out in the stories of participants. The mothers didn’t resent the internet but shared their daughters interest in and reliance on it, if not claiming to access it with equal proficiency. While several expressed concern that it might prevent their daughters from participating more fully in real world events, none felt obliged to monitor their teen daughters who they credited with having and using good judgment. For their part, the teen young adult women I spoke to did not feel that time spent on the internet left them cut off from real life but instead described it as helping to guide their life decisions and improving actual know-how. Indeed, it was actually the women of my generation who remembered feeling unprepared for life’s events and leaving home to learn through experience. They acknowledged with optimism that the current generation of teens have found virtual windows that allow them to stay home and be informed by communication technologies we never knew and they expect. In my study, participants of both generations depicted the internet as more of a bringer of light than a source of darkness or isolation.

***

PART II

Our Daughters: Virtual Information, Actual Advice, and Mom for Money

To initiate a conversation with each of the four girls, ages 16 – 20, about their attitudes to their computers and to their moms, I began indirectly by asking what they usually do when they want to learn more about something. Not surprisingly, all four answered that they would go on the internet, and, of these, three used the phrase “I’d Google it.” An interesting thread among their responses was that several initially downplayed the time they spent on the internet, but as they talked the picture changed to reveal they usually stayed logged on even when not directly engaged in internet activity. Most reported being online for extended periods but found it difficult to give an exact number of hours for actual use.

None were concerned that their network activities might be cutting them off from real world work or engagement, but they cited this as a concern commonly expressed by parents. Two said outright that their mothers wanted them to do something — to see friends, to play sports, to go out: “You know, to go out of your house and do stuff with others, maybe something organized, with a coach or a leader.” When teen girls made a distinction between real and virtual activity, they saw the two as complementary, not antithetical. One respondent, devoted to horseback riding, explained, “I’m especially interested in a chat group that has expert riders from all over North America. The members are kind of elite, and whatever they say is worth listening to.” Another girl also described supporting her hobby of cooking by turning to the internet: “I found out about this tool called a mezza luna — it’s crescent shaped, for chopping herbs. I ordered it. I might be able to get it here, but then I’d actually have to get dressed and go out in the cold.” In general, the girls depicted seeking internet information as supporting real world interests and undertakings and improving their performance by applying what they found.

While all four girls reported turning to the internet for various forms of information, they did not claim to use it as a primary source of advice about personal problems and questions. Most preferred turning to friends to talk about “personal things,” noting that “friends have usually gone through similar things and know what to say.” The shared sentiment seemed to be that it was best if possible to get through personal struggles without getting mom involved — one girl said, “She just worries and makes it worse,” while another said, “She has her own worries with dad.” When pressed, most picked a parent as a person they might go to in more extreme situations — half picked mom and the other half dad — not for advice with emotional situations or interpersonal struggles but for actual help. They were in agreement on picking the option of consulting a parent for big problems — needing money, car problems.

While advice and help were said to come from human sources, several noted how stories and images from media and print sources also played a role in shaping their thinking about relationships and dating: One said: “I think I have created a picture in my mind of an ideal guy, from books and movies. I mean, you just don’t see boys around like Edward in Twilight — he actually dresses up and goes to nice places, drives expensive cars. I don’t find many of these types around in real life.” So while the internet is always in the ready to provide various kinds of information, the girls are aware of having other windows opening to the outside world.

In general, what I heard from these girls is that they know how to find what they want or need to know. Picturing contemporary teens as “internet-only” dependent is inaccurate (at least according to my small sample). They are aware of having and using more options.

***

PART III

My Generation: Lost in the Nuclear Family

If our daughters’ generation describe themselves as growing up in the know, such is not the way many of us who were born in the 1950s and early 1960s remember the process. According to women's accounts in the recent three-volume series Dropped Threads, many women who were raised in the mid-twentieth century grew up with a sense of being isolated and unprepared, and tell stories of lack, loss, and silence. The personal narratives collected in each of the volumes demonstrate how “What we [weren’t] told” is especially resonant for women born just around and just after mid-twentieth century. The pattern they describe is certainly one I recognize as having formed my life. Like many, I grew up without much access to resources outside the home: housed in a city suburb among strangers, boxed in a single-family dwelling, dependent on immediate family. Because my father, like many who headed up these households, was transferred every few years as part of his work, we experienced further disruption and isolation as we were forced to move to a new neighborhood every few years.

Growing up, I felt that my family was my destiny, controlling what I did and said. And what I didn’t say or do. For much emphasis was placed on things that were not to be tolerated, things that “in this family” were not said or done. We had some long silences and heavy secrets. Many analysts of mid-century suburban life have suggested that it was characterized by restrictions and disillusionment. S.D. Clark’s observation that the problem in mid-century suburban life lay with “the solitary family” more than with “the solitary individual” suggests that feelings of being isolated both with and within one’s family were widespread (Clark 190).

Ourselves: Leaving Home to Learn about Life

Many of the happy and enlightening moments I experienced growing up took place out of house and away from family: at summer camp, on car trips with family friends, and at sleepovers. When I talked to the moms my age about their memories of growing up and teen years, their stories also emphasized the importance of leaving the house. These women in their late 40s and early 50s, now moms of teen girls, described growing up in the late 60s and early 70s as a learn-as-you-go-process, often involving hard experiences about matters associated with adult life. They remembered having to physically leave the house to learn about such things as sex and other taboo topics such as alcohol, drugs, and even death. Like their daughters, they expressed a disinclination to turn to their mothers for information and advice.

One woman who now has a close relationship with her parents remembered her mom and dad as people she avoided as a teen. She remembered: “I never left the house that they didn’t call out — not ‘I love you’ — but ‘Be careful.’ With my own girls, I try to let them be.” Rather than turning to her mom, she remembered turning to friends as well as learning through experience. “We just got out of the house and then did whatever we wanted. My parents just didn’t get it.”

One participant remembered her mom as expecting respect and compliance. Another remembered her mom as “way too busy” caring for younger siblings. She recalled having a lot of freedom to come and go — more than she gives her own daughter — and learning from friends and experience what she wanted to know. “They never really knew what we were up to. I think there was more distance between them and us. I mean now we know too much about what they do, where they are.”

Moms: Remembering and Forgetting Growing Up

Two odd patterns emerge in the way women of my generation remember their teen years. First was their tendency to downplay the presence and influence of television and print media. Only one respondent mentioned television in her memory narrative. Yet when I asked about it directly, everyone acknowledged it played a lead role in shaping leisure and thinking. This solicited memory exemplifies how influential TV was in modeling elements of teen culture in the early 70s: “Remember the Saturday morning teen dance shows, how we’d watch them for the music, but also to see what dances were in, what clothes and hairstyles they were wearing? Even what they said, ‘with it’ phrases like ‘far out’ or ‘sad.’ A lot of times I’d watch with my brothers, and we’d all comment on what we thought was worth trying.” Asked directly, participants also affirmed that magazines and books provided a source of information about popular and political culture. So although the dominant narrative was of isolation and under-preparation — with home depicted as a place you had to leave in order to learn — offsetting this to some degree was a competing story of having access to information in televised and print sources.

"TV Shot: 'I Dream of Jeannie' 1970s" by danagraves

Exactly the dream world fare we watched in the 60s.

There are several ways to account for why respondents may have foregrounded their sense of isolation. First has to do with the nature of memory and remembering, which memory theorists define as “an act of imagination [. . .] a creative, constructive process” (Bolles xi). All participants were required to sign an ethics consent form prior to being interviewed, and the form designated “Moms and Teens and the Internet” as the title of my study, providing a cue that may have caused participants to summon internet-centred memories: Rather than thinking about what TV offered, they were more focused on thinking about the effects of not having the internet. Coupled with the tricks of memory are McLuhan’s laws of media, one of which is called the law of obsolescence. By this rule, older technologies do not disappear but recede “into a subsidiary role in culture” (Understanding Media 296). Anachronistic television and print media fade even in memory.

It is also interesting that women of my generation emphasize the distance between themselves and their mothers in contrast to the closeness they feel they have established with their own teen daughters. They all claimed to be more open with their daughters than their moms had been with them. Several even claimed to be privy to the details of their teen’s lives. Yet this level of intimacy was out of sync with what their daughters had reported. Rather than turning to their mothers for information or advice, the teens had selected the internet and friends as primary go-to sources. Ironically, the intergenerational commonality that emerged was what might be called a “Don’t tell Mom” rule — reluctance to seek personal advice from mom, coupled with a belief that parents do not know what teens are doing.

In some part, mothers of my generation may actually be staking their claim to greater sharing and openness with their daughters on the basis of shared sense of commitment to and immersion in new technology. To build on Tapscott’s argument that families have been democratized by cross-generational commitment to computer technology by applying it to mother-daughter relations, we might speculate that mothers have surrendered some of their authority over — and perhaps even grown dependent on — daughters who have demonstrated computer competency. Several mothers reported asking daughters to help them with Facebook, PowerPoint or adapting apps. Using the computer — the process and practice — may be a basis for sharing and bonding. As a result of a shared interest in technology, mothers may characterize their relationship with their daughters as relatively open, with technology no longer being a source of rule-making and contention as it was when we were growing up arguing for rights and access.

While Tapscott’s contention that technology has democratized family life provides a lens through which to view the tendency of women of my generation to characterize their relationship with their daughters as friendly and forthright, feminist theory adds another perspective. Feminist mothering theorists point out that women of my generation were raised by mothers who were operating within “the institution of motherhood,” which had the effect of regulating the relationship between mother and child. While the institution is “invisible,” it nevertheless prescribes boundaries and ideals about bearing and caring for children (Green 22). In place of devoting oneself to institutionalized motherhood and its concomitant characteristics of authoritarianism and self sacrifice, many women of my generation, whether they consider themselves feminist mothers or have been more indirectly influenced by feminism in the culture, have raised children with an ethics of care that takes into account the needs of self, children, and community.

***

PART IV

Being Cyborg Together: “We’re inside what we make and it’s inside us”

Feminist theorizing about techno-bodies is also helpful here. Moving into the twenty-first century, it is hard to argue that any of us remain “a thing of nature” rather than “a sign of culture” (Balsama 3). Most of us have relied on various forms of medical intervention — from aspirins to operations — and every day we make our way in a world of machines. Katherine Hayles argues that we are already posthuman, with virtual lives often inseparable from actual ones. Cyberfeminists have argued that cyberspace may be a site where women can reconstruct and realign themselves without the baggage of oppressive gender categories.

For Donna Haraway, the process of becoming cyborg is largely optimistic because hybridization has the potential to reenergize human lives and relations by releasing women from historicized vulnerability and gendered inferiority. Being cyborg is a flexible identity, neither fully machine nor human, neither wholly textual nor material, but always becoming in response to experience rather than attempting to recapture illusory wholeness. Because cyborg origins are not tied to heteronormativity, or even more abstractly to the myth of the garden, the “cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family” (151). For the purposes of this argument, conceptualizing mothers and daughters as cyborg women allows us to conceptualize these two figures in a non-familial form of relationship — one that might be described using techno-friendly verbs such as “integrated” or “networked.” Rather than privileging mothering-daughtering roles by keeping our focus solely on this relationship, thinking of mother and daughter as cyborg women provides another layer of identity outside the domestic grid. The new identity abandons outworn idealized images of mothers as repositories and daughters as seekers of advice by imagining both as connected to a broad network, open and mobile. From this perspective, computers and the internet have not invaded our homes but come in peace, part of the process of remaking our lives and world with science and technology that has been intensifying since the mid-twentieth century. As Haraway notes, there are oppressive terrors attached to this technology, but there are also possibilities for building new ways and things.

One way of representing how family dynamics remain real at the same time as they are being rewritten can be seen in an example drawn from Facebook. There is the option on profile pages that allows users to list immediate family. This program is especially popular with young teens, many of whom take the opportunity to substitute or supplement the names of friends: Best friends are often listed as mother, father, or sibling. Often actual family names are not left off the list but are mixed into the list of friends. Older readers will remember the saying that “You can choose your friends but not your family,” often invoked to coax family members to show greater tolerance toward each other. While the saying is not rendered false, its meaning is challenged by the example from Facebook, for in this realm, albeit in a limited way, it is possible to choose your family. The broad point to take from this example is that familial bonds are still active and influential, but they are also being reimagined in virtual life.

"Morgan Rogers and Jaqueline McLeod Rogers" by W. Rogers.

Extending help.

In one of her explanations of turning cyborg, Haraway says that we have become — taken into ourselves — the things we produce: “Technology is not neutral. We’re inside what we make, and it’s inside us. We’re living in a world of connections — and it matters which ones get made and unmade” (in Kunzru, n.pag.). Her explanation has particular resonance here, for women of my generation have physically produced our daughters so that we’re “inside” them and they’re “inside” us. If they are techno-oriented, then by Haraway’s logic we are in a process of internalizing what they are and know, for we are connected. Of course Haraway’s primary reference is not to the connection between people, but to the connection between us and the machines we make. Her comment, “We’re inside what we make and it’s inside us” is reminiscent of McLuhan’s observation: “We shape our tools, and afterwards our tools shape us” (qtd. in Coupland, 107). The difference between the language each uses to explain the terms of connection is that Haraway’s is more organic and embodied, more completely interactive than McLuhan’s. Her description of the relationship sounds consensual and organic while his sounds more conflicted and inescapable. In her version, we may have some control over human–machine mixing and decide which connections “get made and unmade.”

Haraway’s perspective captures the optimistic spirit of the conversations I had with both moms and daughters about the role of the internet in our lives — about how this human-made thing has gotten “inside us.” The moms accepted its presence in our homes and lives as de facto and helpful, regarded it as providing their daughters with advantages we did not have, and admired their daughters’ abilities to access virtual-space opportunities. For their own part, they expressed commitment to using the computer and to continuing to learn more. The daughters also accepted the computer as integral to life. Their responses indicate that Haraway’s question about our integration with technology is less radical than rhetorical: “Why should our bodies end at the skin, or include at best other beings encapsulated by skin?” (178).

Being Connected, Keeping Watchful

"Cyborg Modesty" by Hartley Anne Rogers

Seeing ourselves cyborg.

While cyborg imagery has frequently been associated with darkness and danger in the popular imagination, its positive history in the context of feminist theorizing continues to play out in my study, with the machine as a bonding agent for moms and daughters. Before I conducted interviews for this study, I had imagined the internet as a probable source of tension between mother and daughter — a Hades figure usurping the daughter’s attention and detracting from the mother’s hold. Alternately, I had also mused about the possibility of the computer being perceived as a “cy-mom” stand-in, always up to the challenge of providing answers without asking messy nagging questions.

Yet being usurped or replaced turned out to be a non-issue given that consulting mom about intimate matters was not something daughters of either generation was prone to do. Our daughters find things they want to see and know in virtual space, and in this geography they are also able to air their thoughts. If “don’t ask don’t tell” captured the family mantra of many women of my generation who felt isolated at home, our daughters are being raised with access to a virtual world of show and tell. Many women of my generation are entering this virtual world too, often with the help of their daughters.

Thus, not only is it inaccurate to say that the role of mom is now being performed by the laptop on the kitchen counter — inaccurate to picture moms pushed aside from their former role of dispensing advice and providing information — it is also inaccurate to say that daughters control this technology. It may be fairer to see the computer as changing family communication patterns so that we share an interest in learning to be more effective users of current technology and adapters of innovations. And if cyberfeminists are right, using this technology opens up possible worlds.

"iPad Woman: The wired and wireless future

of media and infotainment" by tsevis

Always reflecting on changing.

Optimism about the role of the internet in the lives and bonding of mothers and daughters, however, is not untempered. Twentieth-century public intellectual Margaret Mead recommended, first in Coming of Age in Samoa and following that in other popular publications, that North Americans make their homes more open to release children from the confines of nuclear family. Because her recommendations were based on observing the strengths of non-technological societies, hers was a reversionary “sweet dream,” a hope for us to get back to the garden and recapture innocence. Ironically, the technological innovations developed in our society have answered her call for more openness and sharing. But rather than the pre-industrial and pastoral enclave she envisioned, our village is global and virtual. While computer technology may have become one of the ties that bind moms to daughters as we share cyborg lives and futures, we also share the responsibility for watching, remaking — even unmaking — this connection. This is not a matter of surveillance — of one group monitoring another, the way we do young children. Rather it is a matter of not becoming entirely naturalized to our cyborg lives — of not allowing the internet to get so far inside us that there is no separation between it and us — so that we can muster the critical awareness and mobility necessary to “un[or re-] make” this connection.

***

References

Balsamo, Anne. Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women. London: Duke UP, 1997. Print.

Bolles, Edmund Blair. Remembering and Forgetting: An Inquiry into the Nature of Memory. New York: Walker, 1988. Print.

Clark, S.D. Suburban Society. Toronto: U of T Press, 1966. Print.

Coupland, Douglas. Marshall McLuhan. Toronto: 2010, Penguin. Print.

Green, Fiona. Feminist Mothering in Theory and Practice 1985-95: A Study in Transformative Politics. Lewiston NY: Edwin Mellen, 2009. Print.

Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York, Routledge, 1991. Print.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999. Print.

Kunzru, Hari. “You are Cyborg: For Donna Haraway, We are Already Assimilated.” Wired, 5.02 February 1997. Web. http://www.wired.com/wired/archives/5.02/ffharaway.html.

McKay, Sharon and Kim Zazur. Good to Go: A Practical Guide to Adulthood. Toronto: Penguin, 2008.

Mitchell, Joni. “Woodstock.”

O’Reilly, Andrea. The Encyclopedia of Motherhood, vol. 1. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2010. Print.

Penguin Books. "GOOD TO GO A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO ADULTHOOD." Penguin.Ca. Web. 10 Apr. 2011.

Shields, Carol and Marjorie Anderson, eds. Dropped Threads: What We Aren’t Told. Toronto: Vintage, 2001. Print.

Tapscott, Don. Grown Up Digital: How the Net Generation is Changing your World. New York: McGraw Hill, 2009. Print.

Young, Neil. “After the Gold Rush.” Reprise. 1970.

Jaqueline McLeod Rogers is an Associate Professor in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric and Communications at the University of Winnipeg, an urban campus in the middle of the Canadian Prairies. She has two daughters (Hartley and Morgan), who keep [her] growing, and has learned about technology and other things from talented research assistants, “student-daughters” (Maggie, Marissa, Alison, and Allison). She has recently published several creative non-fiction articles in Writing on the Edge, and academic articles on topics such as narrative theory, research methods, and Margaret Mead.