A Name on the Tree

Laura Davies

Rhetoric, to me, is largely about the power of words. Words contend, persuade, construct history, deconstruct history, and form rituals. Some of the most powerful words around are our names, the curious mix of letters and sounds that define us and become us. A newborn’s name only seems awkward for a day or so, and then that little person becomes inseparable from his or her name. Names have always piqued my interest, ever since the day I was able to read my own on my family tree. My essay, "A Name on the Tree," is about the rhetoric embedded in family names: the statements, arguments, and histories family names make. This essay explores what family names can reveal to us about our family's history and our own identity and place in that history.

Into the hive of cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents, a park ranger drives up in his golf cart. Pointing to the poster-sized Barrett family tree hanging on the tree trunk that anchors the picnic site, he tells the group gathered around to take it down. You’re not allowed to put nails in the park trees.

My tall-as-almighty Uncle Eddie, peering down at the ranger, laughs: "My uncle drove that nail in! Forty years ago!"

***

The Barrett family banner

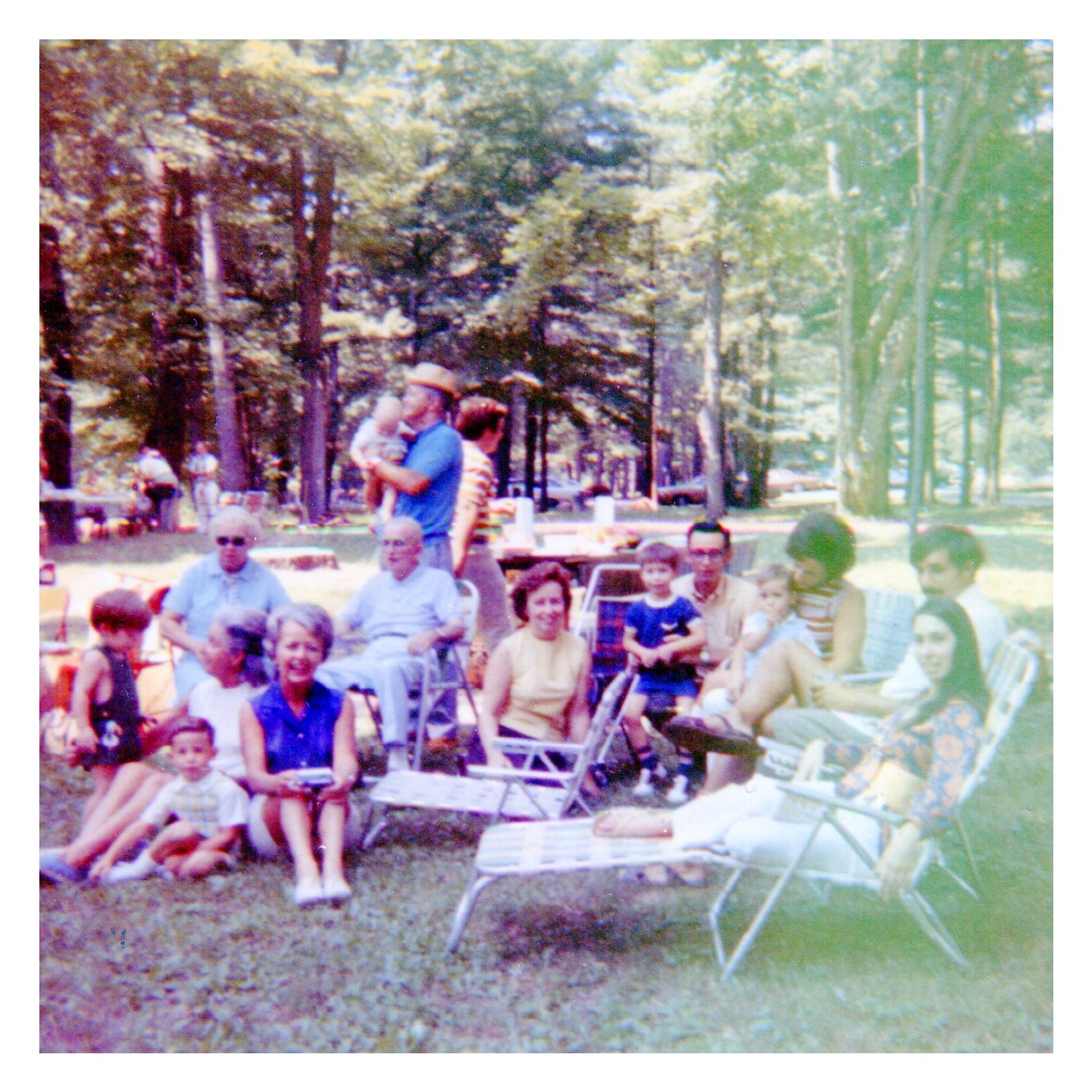

Every year, on the first Sunday of August, my mother’s family gathers at Look Memorial Park in Northampton, Massachusetts, and celebrates the Barrett Family Picnic. The picnic started in the backyard of James Edward and Mary Elizabeth Barrett in 1946 as an annual gathering of their seven children and dozens of grandchildren. As the numbers swelled in the 1960s, the yearly picnic moved down the road from Holyoke to Look Park. Now, over fifty years later, the Barrett descendents—now numbering scores of great- and great-great grandchildren—still make the pilgrimage, rain or shine, every August.

The Barrett Family Picnic in the early 1980s

I love the Barrett Family Picnic. Every January, when I get a new calendar, I flip through the months, marking birthdays, the Fourth of July, Christmas, and the first Sunday in August. My mother’s sister Mary now manages the picnic, and I wait every year for her email detailing set-up and food responsibilities: who will bring the tables, the paper plates, the appetizers, the hot dogs, the burlap sacks of corn-on-the-cob.

There’s a liturgy attached to the picnic, one that I’m working on installing reverence for in my own children, four of the Barrett great-great grandchildren. We arrive around noon, placing our cooler of drinks by a picnic table. We each snag a cheeseburger that the uncles are flipping on the charcoal grills. Then we walk across the softball field, get on the kiddie train with our cousins, putt-putt-putt around the park, and scream our heads off as the train pulls through the short tunnel. We walk back, pile our plates high with Cece’s congo bars and Theresa’s whoopie pies and try to find the hidden pie box that holds Joanie’s chocolate pie, cut into tiny slivers. Then we head down to the paddle boats, splitting up in groups of threes and fours. We want to get around the island twice, so we race around the first time, beating the park attendant’s whistle to come back, and chug leisurely around the second time. Though it’s strictly against park rules to jump boats, we do.

On the paddle boats in 2008

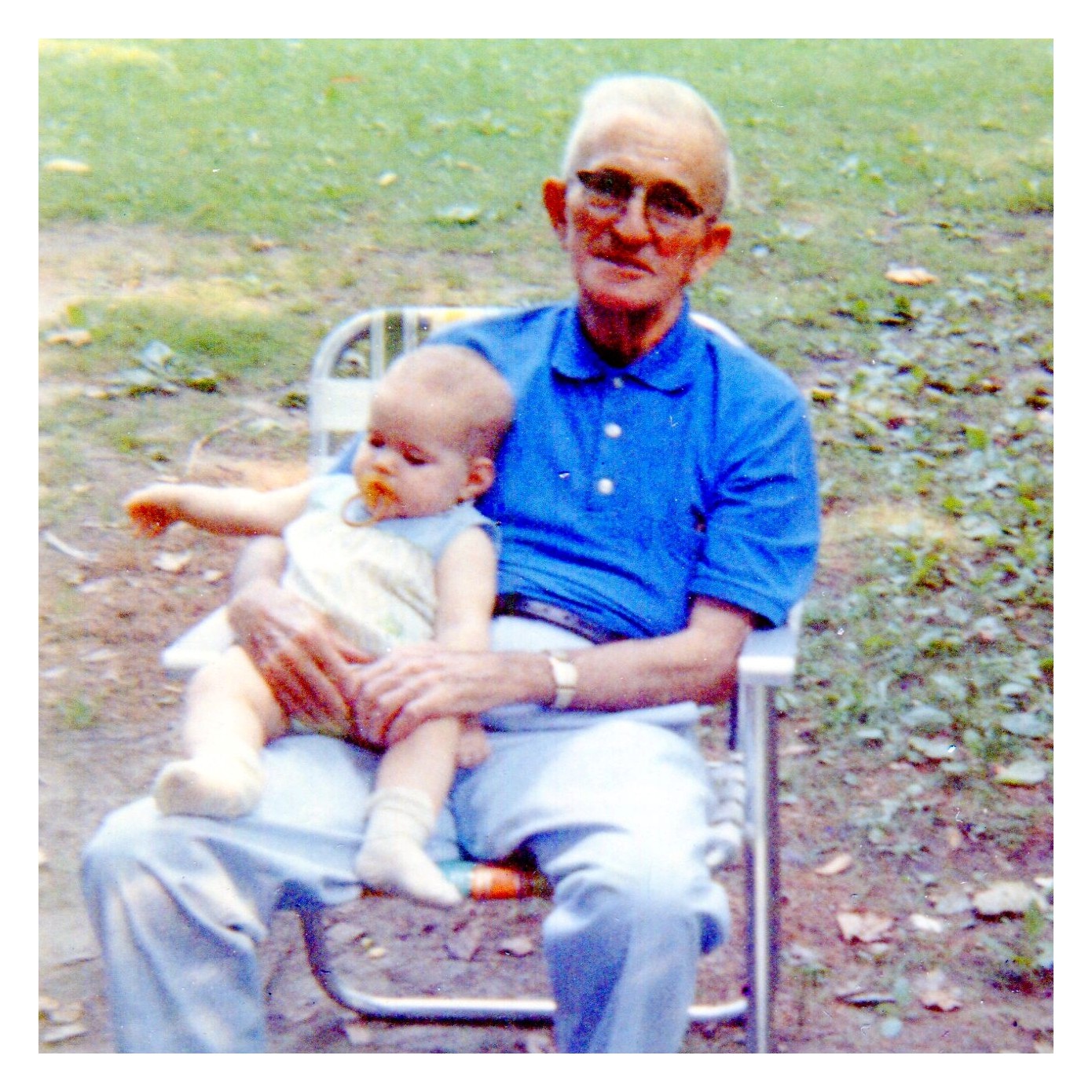

James E. Barrett (Bompie) and grandchild in 1969

We walk back to the picnic site and cajole the younger cousins into shucking the bags of corn. We visit with Grandpa, get teased by Uncle Mark (who’s wearing his Hawaiian shirt), talk with our cousins, and grab another round of hot dogs, baked beans, and congo bars. We flip through the photo albums that Mary Agnes brought, faded candids of past Barrett family picnics. When the mosquitoes start biting in the early evening, people start saying their goodbyes and drift away. We’ll see them next year.

Talking around the picnic tables at one of

the first Look Park Barrett Family picnics

The consistency of the Barrett Family Picnic ritual, re-lived every August, gives all of us a common place to begin, a background rhythm that drives our conversations and our understanding of each other. My relationships with my cousins, aunts, and uncles were formed around the Look Park picnic tables, and it is there that I return each year to talk, to catch up, and to add to the stories that become our family history. Each year, we celebrate the brand-new babies and welcome new friends and partners attending their first Barrett Family Picnic. We also talk about who’s not there—the cousin serving abroad, another starting a new job, the sister just days away from her due date, the uncle too sick to come this year, the grandmother now gone. We talk, too, about past picnics, the stories set at Look Park that have become inscribed as family legends: "Remember when Johnny and Matt chased down the kids who threw rocks at us on the train?" "Remember when James fell into the pond when he was trying to jump paddle boats?" "Remember that park ranger trying to tell us what to do, as if he didn’t know we owned this park the first Sunday in August?"

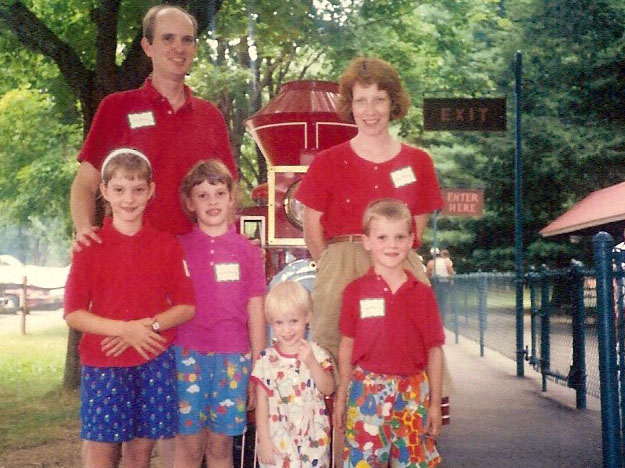

The author with her siblings and parents

in front of the Look Park kiddie train in 1991

The author with her children and husband

in front of the Look Park kiddie train in 2009

My favorite part of the Barrett Family Picnic, though, is finding my name on the Barrett family tree that is posted each year. There I am—Laura Joan Panning Davies—the second daughter of the second daughter of James E. Barrett’s fourth son, Edward. I like crossing my eyes, seeing the matrix of names blur together into a grayish cloud, wondering if James E. and Mary E. Barrett (or Bompie and Nanan, as their grandchildren called them) knew what they were starting when they married at the turn of the 20th century. It’s almost Old Testament in scale, Abraham trying to count his descendents among the stars.

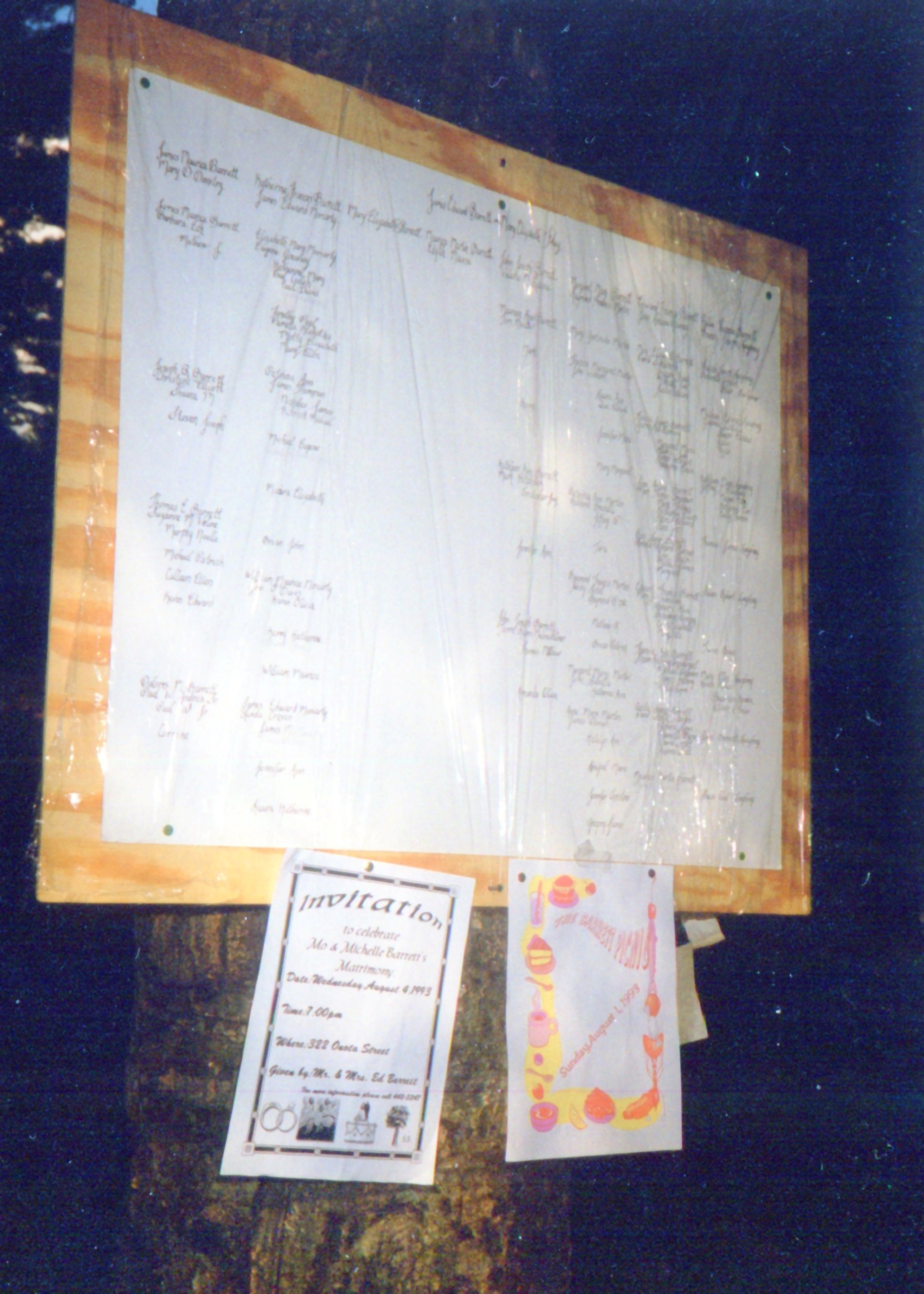

The Barrett Family Tree,

nailed up on the Look Park tree

I don’t just look at my name, though. I trace family names down the tree: my great-grandfather’s James is echoed in his first son’s name, my brother’s name, and the middle names of other first and second cousins. Margaret (called Margie, Margaret, Maggie) is there, too, along with the Irish Catholic standards of Mary, John, Katherine, and Edward. My middle name—Joan—is my grandmother’s and godmother’s name. Studying the family tree each year solidifies the deep connection I feel to my family, a bond that is cemented through our names.

Some people, when naming their children, choose something unique, claiming that they don’t want their children to be burdened by an older relative’s legacy. Some parents alter a name’s traditional spelling or even invent a name for their child. They want something that underscores their child’s individuality.

Young Barrett cousins at the picnic in 1989

I feel differently. A family name, repeated down the family tree, makes the argument that you are part of something bigger, a constellation of stories and people who all had a part in you, miracle of miracles, being here. It’s rhetoric, really: instead of a name that argues that you are a separate individual, a family name places you among others. A family name is a little piece of evidence that you carry with you each day, supporting a larger argument that you are not alone: that other men and women, good and bad, tragic or comic, are an inseparable part of you. Your individuality isn’t completely absent in a family name: each person who carries the name adds to its story, layer on top of layer. And although parents can choose to give their child a family name, tying them to past branches on the tree, that child, as they grow, can choose to embrace, ignore, or reject the history within the name.

A few of the Barrett cousins in 2007

Family names are a quiet sort of rhetoric. The arguments and stories that they hold are never really brought out in the spotlight except for the moment a newly-born member of the family is named or when all the names are gathered together, like on a family tree, and the trends and connections between them suddenly become apparent. Apart from these times, our names stay silent and unnoticed. However, teasing out the stories embedded in our names can help us understand our family, our history, ourselves, and our place in this world.

My oldest son’s name is filled with history. His name—Stewart MacDonald—is shared with his paternal grandfather and uncle, who are named after my husband’s great-uncle, Stewart MacDonald, who was always called Buddy. Buddy was a 19-year-old Navy lieutenant when his plane, flying off for a bombing mission over Nazi-controlled France, broke apart over the English Channel. Buddy’s name is now carved in granite on a World War II memorial in Weston, Massachusetts.

All gathered together in 1969

The story doesn’t stop there, though. Buddy was named after another Stewart MacDonald: my husband’s great-grandfather, who raised Buddy, his sister-in-law’s out-of-wedlock son, as his own. This Stewart MacDonald was the eleventh of fourteen children in a Nova Scotia coalmine family, and his name was an ode to his mother’s family—the Stewarts—and his father’s—the MacDonalds. My husband and I journeyed to Nova Scotia on our honeymoon and spent a few days hiking through the Stewart and MacDonald homelands, the rugged Atlantic countryside where these Scottish immigrants carved out their living. All these men and women, stretching over generations and nations, probably never imagined a young Stewart MacDonald playing t-ball in central New York. But our Mac is a living argument to their critical importance: their stories, their shared name, swirled up in his.

My second son, with the same ocean-colored eyes as his father, looks, as my mother says, just like her Loughery cousins. His middle name—Martin—is the name of both James E. Barrett’s father and my own father’s godfather. Sometimes the name connection isn’t so apparent. If you look on the Barrett family tree, you won’t find a Beatrice, and you won’t find it on any of our other genealogy charts. But it’s part of our daughter’s name—Adaline Beatrice—as an artifact of family history. Adaline was the fourth granddaughter born the summer after her grandmother and great-grandmother, two family matriarchs, died of cancer. Adaline and her three little cousins signaled new bright life after a year of sickness and loss, so we marked her as who she meant to us and who she continues to be: Beatrice, or “bringer of joy.”

The author on the Look Park train in 1991,

surrounded by cousins, aunts, and uncles

Our youngest is the fourth generation of John—not a junior, but still the spitting image of his father. On the frosty February morning when he was born, though, I thought of the first Sunday in August, which can be sweltering hot and humid in New England. The baby’s middle name is Barrett, and there he is on the Barrett family tree this year, a name that claims an undeniable tie between this baby boy, my grandfather, Nanan and Bompie, and the Irish immigrants before them. There is his place in the universe of people, a name written on a family tree, etched on gravestones and memorials. Long after the rusty nails fall out of the Look Park trees, the crumbs on the chocolate pie plate get licked up clean, and the family legends get lost and forgotten, the names will still be there, calling out a family history, an argument that whispers, "You belong. You’re part of the story."

Laura is a full-time writing instructor at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York. She is also completing her doctorate in Composition and Cultural Rhetoric at Syracuse University. Laura’s academic interests span from studying writing program administration and educational assessment to new media and creative nonfiction. She cares deeply about education, ethical communication and labor practices, and her family.