Something's Fishy Here

Kate Comer

I wrote this piece as a sort of Harlot test run. When we began talking about the need for public-oriented rhetorical criticism, Jim Fredal challenged me to figure out what that might look like. I'd recently written a rather academic analysis of Hans Christian Andersen's original "Little Mermaid" and was hoping to make it relevant/current; Disney's version had just been rereleased in a "Platinum Edition" DVD and was being adapted into a Broadway show. So it made sense to put it all together, using my sister as my ideal audience: smart, fun, feminist. . . and concerned about her new baby's exposure to the dangers of Disney rhetoric. This has been the most enjoyable writing experience I've ever had.

Once upon a summer vacation, a young girl in New Jersey was delighted, scared, and maybe a little scarred by a rainy afternoon spent with The Little Mermaid. Or rather, I should say, a "Little Mermaid" because the movie I watched that day, one based on Hans Christian Andersen's sad fairy tale, bears only superficial resemblance to the Disney version that now dominates the marketplace. I watched the Disney one, too, later, and I loved it, at least in part because of the saccharine comfort it offered. (And I'm not ashamed; it's a tasty little morsel.) But I never could forget that rainy afternoon crying over the unrequited love, watery grave, and bittersweet salvation of Andersen's little mermaid. Now, returning to these stories as an adult, I'm not sure which pleases or bothers me more. I understand how lucky I was to have had both, to have been forced to reconcile (or not) their morals and messages, to have seen just how a story can change with the teller and the times. I like to think the little mermaid taught me that; I am less comfortable with what else she might have taught me.

Meghan at 10 months

When I tell my own story, the one about my fascination with the dynamic and sometimes dangerous power of traditional tales, it often begins with this early exposure to various little mermaids. Another version begins with my first teaching experience, when the smart, sexualized revisions of traditional folktales in Angela Carter's Bloody Chamber generated passion, debate, and humor in a required first-year college writing course. (Seriously, that's a big deal. I'm talking about freshmen at a co-ed state school here.) Yet another links my concern over the insidious rhetoric of these formative stories—originals and revisions—that will one day influence my baby niece Meghan, whom I desperately wish to defend from the attack of the princess brigade.

Cue heartstrings. Oh, won't somebody please think of the children? Relax, I'm not going to launch the all-too-familiar-and-therefore-passé anti-Disney tirade. (Though if given the slightest encouragement and a martini, I make no promises.) I bring Meghan up only to explain my personal interest, my genuine (read: not predetermined) curiosity about what messages she'll be fed. And I want to make it clear that I'm not looking to take away anyone's entertainment candy or make you feel guilty for indulging. I love my E! and romantic comedy confections as much as (some might say more than) anyone. At most, I might suggest a little mental exercise and a well-balanced diet. No big whoop.

And so, not to belabor a metaphor, I propose that we take a closer look at some ingredients and nutritional values of some standard fare. On our menu today: seafood. The story of the little mermaid offers a unique case study in the rhetoric of the formative stories of childhood, and not just because of our personal history. Unlike most of the popular fairy tales—"Cinderella", "Beauty and the Beast", "Sleeping Beauty"—the story of "The Little Mermaid" can be traced directly to one particular text and author. That means that when we read Andersen's story, we are starting at baseline rather than having to sift through murky oral traditions. (I won't dwell on the mythic significance and cultural associations with the mermaid figure other than to note that both domesticate the feminine threat by silencing the seductive, subversive voice of the siren. As the density of that statement indicates, I shouldn't go into it here.) So a straightforward comparison of the messages of these two texts is possible, even reasonable.

What's more, there are some interesting parallels between the original publication of "The Little Mermaid" in 1837 and the release of The Little Mermaid in 1989. Both creators explicitly and successfully targeted a mixed audience of children and adults, changing the stakes of the whole fairy tale game in the marketplace and in cultural consciousness. Both were wildly popular right away, changing the creators' fates and fortunes; they each marked a definitive shift in the creators' genres of choice and also in the genre their audiences overwhelmingly associate with the name. Both found a lucrative product in a strong market and sold it for all it was worth. Andersen produced hundreds of tales and rose above humble beginnings and personal insecurities to become a literary icon and classic success story. Mermaid was Disney's first fairy tale film in 30 years, and its unprecedented success saved the animation division from irrelevance or closure. And yeah, Disney's Magic Kingdom is something of an icon.

(Though Walt is certainly a symbolic figure, I refer here and throughout to the vast corporate entity that bears his name.) I'm not really prepared to make any grand arguments about these coincidences, I just found them worth mentioning. They seem to suggest, at least, a certain power in the mermaid's tale.And that's where the parallels end. Okay, not really. . . but as we all know, Disney took some serious liberties with the original, retaining only the basic premise: beautiful adolescent mermaid wants to be human, falls in love, and exchanges her voice for legs so she can chase her prince. In other essentials, like mood and character, violence and sex, and oh, death, the stories split like the mermaid's tail. I can't begin to explore the seemingly endless shades of difference between the Andersen story and the Disney film here. I just want to look at the biggies, the fundamental changes that so drastically alter not just the plot of the story but its point(s).

Andersen

Disney

The (anonymous) youngest mermaid princess is unusual, quiet, wistful, and suffers nobly throughout. Though lonely, she has a female support system in her sisters, grandmother, and eventually the daughters of the air. Her father is a shadowy figure with no impact.

Ariel, the youngest mermaid princess, is adventurous and vivacious, spunky and brave. She has silly (male) animal friends and lots of fun. She is daddy's little girl but wishes he weren't so overbearing. Her sisters are shadowy figures with no impact.

After she learns from her grandmother that she must be loved by a man in order to gain a soul, the mermaid approaches the sea witch. The witch explains that the transformation will cause constant physical agony. No deadline is set, but the mermaid will die if the prince marries another. For payment, she must cut out her tongue to hand over her voice.

After an argument with her father, the vulnerable mermaid is lured by the sea witch's minions. The witch convinces her, through a persuasive song and dance, to take her deal. The stipulation is that the mermaid has three days to make the prince love/kiss her; if she fails she will belong to the witch. For payment, she must give up the glowing essence of her voice.

The prince sees the silent and submissive mermaid as a slave, though he does grow rather fond of her. She dances for his amusement, sleeps on a cushion outside his door, and listens to his daydreams about the woman he thinks saved him from a shipwreck. Unable to explain that she is his true love, the mermaid must dance at his wedding to the wrong woman, a human princess. And then die.

Though haunted by the memory of the woman who saved him from a shipwreck, the prince falls in love with the mermaid, who is treated like a royal guest. Just as he decides to propose, the witch betrays her deal and uses the stolen voice to cast a spell on the prince. The mermaid's friends reveal the truth, but too late: She belongs to the witch, who trades her soul for that of the king. The witch gets the crown and unleashes her fury. When the prince saves the mermaid's life, order is restored.

She dies. After a long and painful trial, the little mermaid fails to win the prince's love or the immortal soul that comes along with it. Given a final chance to save herself by killing her love, she chooses death. Suddenly, the spirits of the air lift her up; they explain that because of her virtue, she may spend 300 years earning a soul through good deeds.

She gets married. After a brief and delightful courtship, the prince falls in love with Ariel. Despite the witch's interference, the mermaid's father and lover save the day. The king understands that he must let his daughter grow up, and gives her legs back. With his blessing, the mermaid and her prince sail off into the sunset.

-

Life can be lonely and difficult, even when you know you're special.

-

Brave women pursue their personal destiny even if it differs from the norm.

-

Love and sex can cause pain.

-

Hierarchies of class and status can set up unbeatable obstacles that perpetuate injustice.

-

Happy endings are not guaranteed.

-

Personal integrity and virtue will be rewarded, just not in the way you might expect.

-

Women's best friends are not other women but rather the men who protect them.

-

Brave young women pursue their men even if it means endangering self and family.

-

Female power and sexuality are dangerous and destructive; male power is natural and necessary.

-

The world is divided into good and evil. You will know them by their looks.

-

Romance is the road to happiness, and marriage is the happily-ever-after toward which all women aspire.

Now that I look at it, I think my work here is done. This comparison, though admittedly grossly oversimplified, is kinda scary. Even by itself, I think, it begins to make an argument for me, offering an overall survey of the black magic Disney's revisionists worked on Andersen's story. But then again, I am a sucker for charts. So in the interest of fairness, let's delve a little deeper into some of these differences. Because I am particularly fond of the subversive voice of the sea witch, I begin with some of her more prophetic and insightful lyrics, a response to Ariel's concern over losing her voice:

You'll have your looks, your pretty face. And don't underestimate the importance of BODY LANGUAGE! HA! The men up there don't like a lot of blather. They think a girl who gossips is a bore. Yes, on land it's much preferred for ladies not to say a word—and after all, dear, what is idle prattle for? Come on, they're not all that impressed with conversation; true gentlemen avoid it when they can. But they dote and swoon and fawn on a lady who's withdrawn. It's she who holds her tongue who gets her man.

A fairly Rules-esque version of feminine wiles and what men really want, with a catchy beat. But the thing is, according to Disney, she's right. Andersen's sea witch makes a comparable assumption: "Your lovely form, your gliding movements, and your eloquent eyes. With these you can easily enchant a human heart." But in fact, the original mermaid's beauty doesn't cause the prince to love her, and the witch's cynicism is not borne out by the plot. Pleased by her devotion and charming ways, he treats her like a pet slave: "She danced time and again, though every time she touched the floor she felt as if she were treading on sharp-edged steel. The Prince said he would keep her with him always, and that she was to have a velvet pillow to sleep on outside his door." Judging by the striking contrast between her pain and his response, perhaps Andersen's story has some subtler messages about the kind of love given to submissive women or the lower classes. . . . The point is, despite all her soulful glances, kisses, and seductive dancing, the human prince chooses to marry one of his own kind.

Andersen's implicit rejection of superficial beauty and seduction as a guarantee of love and happiness only becomes clear with Disney's version as a foil. In the Disney world, the prince does fall in love (at first sight) with her pretty face. Coached by Sebastian the crab, she puckers her lips and bats her eyes; the "Kiss the Girl" musical scene is full of her coy, from-under-the-lash glances—and these tactics work! As Ursula begrudgingly admits, "That little tramp! Ooh, she's better than I thought." Indeed, you've got to be impressed. The prince is smitten, ready to propose, and only shifts his attention because he is enchanted by the devious sea witch. (Note that of course, in the Disney world, his roving eye is not his fault—it's Magic!) That sea witch knows how the world works, apparently. No wonder she has to die. But more on that in a moment. . . .

Whether or not it automatically leads to love, the little mermaid is beautiful, and this beauty is connected to her goodness. Andersen's mermaid, like most literary originals, is described in only the most general terms: She has blue eyes (Andersen was Danish, after all) and soft skin. Nevertheless, her body plays a major role in the story. The transformation of tail to legs feels like "a two-edged sword struck through her frail body," and from that point on she suffers torturous, bloody agony with every graceful step. Andersen dwells repeatedly on her "tender feet" that are lacerated by the harsh earthly realm, a physical representation of her emotional distress. This story certainly does not assume a sheltered life free from stress and disorder, nor does it provide a false sense of security. If we consider the little mermaid's exchange of tail for legs as her sexual self-discovery, or the stabbing pains as menstrual cramps, the physical and emotional complexities in Andersen's tale are at least as realistic as Disney's premature sexualization and tidy transfer of authority over Ariel's body from king to prince.

Now, I'm not saying Andersen's story isn't disturbing, but it's a different kind of disturbing. The Disney female body is mature and heavily sexualized while romantic desire is presented as pure, even platonic. Because this topic has been well-covered, I will satisfy myself with only two comments on Ariel's appearance: (1) I used to think the red hair was a nice departure from the previously uniform blond princesses. . . until my sister brought up the image of the fantasy harem offering a variety of "flavors." (2) Her image, with its enormous head and eyes, disproportionate curves, and scant sea-shell covering, is creepy. (Like those Bratz dolls. Man, they freak me out.) What's creepier is how the animation caresses her. When Ariel first trades tail for legs, she bursts out of the ocean in a classic porn shot, all flipped hair and arched back. As she stands on the beach naked, the shot lingers suggestively below her belly button even as the characters blithely ignore her new vagina. Who's the peeping tom? That ever-popular male gaze, of course, through which actual audiences are treated to impossible physical ideals as well as sexual objectification. . . and simultaneous negation.

Where was I? Oh yes, bodies. That brings me neatly back to a favorite topic: that sexy and rebellious sea witch. In Andersen's story, she lives far from the palace, separated by "tumultuous whirlpools," "a hot seething mire," and a "weird forest." This prophetic and powerful witch is a clear symbol of the natural feminine, the earthy goddess: "She called the ugly fat water snakes her little chickabiddies, and let them crawl and sprawl about on her spongy bosom." This is not to say that Andersen is a big fan, or that his description is glowing. His sea witch is grotesque and scary. She lives in a home made of human bones (from shipwrecks, mind you; no hints of foul play), and she does cut off the mermaid's tongue. But she is not evil, nor is she directly responsible for the mermaid's tragic fate. In fact, she appears for a short scene only to grant the mermaid's request and later offers her, through her sisters, a final chance for reprieve. This witch is helpful and reliable, if vaguely sinister. In general, Andersen's stories have more subtlety than to establish a firm dichotomy between good and bad.

Not so Disney. Although Ursula is arguably the most vividly drawn and exciting character, she is also the capital-V Villainess. Andersen's comparatively liberal refusal to divide the world into opposing forces of good and evil is reversed by the inevitable Disney execution of "evil" or anti-establishment (feminized, often raced, but certainly "other") forces. And Ursula is bad through and through, not just drawn that way. . . though that helps the audience get the point. Unlike the pretty merfolk, she is an octopus: black, fat, and slippery. She seduces, destroys, and collects "poor, unfortunate souls" for sport, creating a hell as her personal garden. And she wears too much makeup. On a more subtle level, the witch is associated with vaginal imagery, from her first appearance in a cave mouth to the whirlpool in which she later traps Ariel. I won't dwell here, but I'm starting to think the urban legends of subliminal sexual messages in Disney cartoons have some real validity.

Back at the level of plot: Though she delights in sabotaging Ariel's love life, Ursula has bigger fish to fry. Exiled for challenging King Triton's claim to the throne, she plots revolution from the fringes of the community. Though the DVD commentary notes that in earlier versions she was the king's sister, Ursula's motives are unexplored in the released film. I guess they didn't want to suggest any valid claim to the throne. (I noticed anyway that the king displays some oppressive and violent tendencies himself.) As it is, the witch's lust for power is explicitly connected to her brash, voluptuous, sexual potency and the dangerous, untamed female power it represents. And when her diabolical plans come to fruition, well, hell hath no fury like a sea witch crowned: "You pitiful, insignificant fools! Now I am the ruler of all the ocean! The waves obey my every whim. The sea and all its spoils bow to my power!" Laughing maniacally, she grows to immense proportions and focuses all of her might on anarchy and vengeance. Finally the tiny, wily prince comes to the rescue, impaling her in the gut with a very phallic ship's mast. Immediately, peace and order are restored. The king regains his rightful crown, marries off his daughter to her worthy prince, and all's right with the world. Hard to find less absolute support for a male-dominated political patriarchy than that! (The last words of the film are "I love you, Daddy." I kid you not.)

Which reminds me. . . In the most surreal moment of Disney's DVD commentary, celebrated queer artist/provocateur John Waters expresses delight over the creators' decision to base their sea witch on Divine, a famous drag queen who brought gender performance to campy heights. I can't help but wonder: How did Waters miss the fact that this character demonizes the very subversion of gender and sex roles Divine represents? How did he not find it problematic that Disney caricatured the drag queen only to kill her? By highlighting two opposing, opposite female characters—even, or especially, if one is a gay man—the Disney film offers audiences a classic set of choices: virgin or whore, straight or queer, love or power, and again, good or evil.

Um, I hate to align myself with evil, but as I said: I like Ursula. (And I don't like binary oppositions.) She adds a much-needed dash of dark comedy to an otherwise syrupy film. And before she too is silenced, her voice offers the most trenchant social commentary contained within the film. The sea witch might not make us comfortable, but she does make us think. Until she's impaled on a penis.

So much for female empowerment. And yet, the creators of Disney's Little Mermaid have the nerve to suggest that they have updated Andersen's tale, brought it up to modern standards. When their depictions of women are questioned, they fall back on excuses of mere entertainment, even going so far as to promote fantasy as a kind of feminism. Perhaps. . . if these characters were empowered to transgress, or at least not enforce, conventions and stereotypes. . . . But they are emphatically not. The power of a princess lies in her (waifish) beauty and her (blank) goodness, both of which produce the (natural) happy ending—marriage. Any other ambition pursued by a woman is subject to suspicion at best, murder at worst. The only safe option, apparently, is silence.

Well, we've long since shaken that patriarchal muzzle, right? No wonder the culture cops are working so hard to put it back on our kids. This, finally, is why the sight of a little girl dressed as a princess makes me shudder. But enough of the bad news. The problem identified, our concern must become this: What do we do now? How do we break Disney's spell? To make it personal again, let's think of the children. And so, I give you Aunt Katie's (Counter)Magic Spell:

Pick wisely.

These tricks are not really for kids. While plenty of fairy tales are appropriate for young children, the ones that deal with sexual awakenings, body changes, and romance should be saved for early/preadolescence. By then they may be ready for these issues. But little kids?! Hardly. Children's lit and film are major industries, and plenty of options are available. I have a friend at Scholastic you should talk to. In the meantime, see my recommended selections below.

Mix it up.

Classic versions of fairy tales aren't the only, or even the best, options. Plenty of playful revisions offer a wealth of interpretations that can balance each other's influence out. Or better yet, the lack of balance will prompt kids to think about those differences and what they mean. Put another way: All those girls clamoring for tiaras and mermaid costumes might reconsider if they knew Andersen's original. At least, I like to think that my early encounter with the little mermaid has something to do with my critical approach to persuasive stories. And I like to think that when Meghan is old enough, she'll learn that lesson, too, instead of just what Disney's selling. My sister promises to provide a test case in reasonable resistance. . . which leads me to:

Talk about it.

These stories offer opportunity for funny, enlightening, and low-pressure conversations about the themes that most concern developing young adults. And though we may instinctively wish to shelter our fragile darlings from any danger or sadness, even imaginary, we may also instinctively know that these lessons will be learned somehow, at some point. It wouldn't be the worst thing in the world if children and adults had a few frank exchanges about loneliness and pain and social injustice—let alone sex and gender stereotypes in pop culture—instead of ignoring these realities and letting Disney do all the talking.

And finally, the secret ingredient:

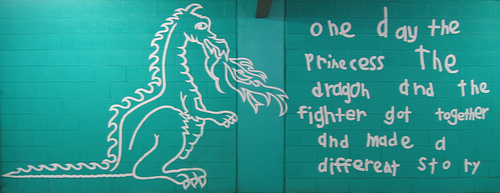

Add creativity.

Children should be the creators as well as receivers of meaning; the best way to learn how to read or watch critically may be to compose critically in various media. Encourage kids to try their hands at the game, to revise the fairy tales they know, or invent their own. Perhaps when they grow up they'll create another set of stories for the next generation. If feminism (hold the post, please) has taught us anything, it's that we have to be critical of patriarchal scripts. And sometimes, we have to write our own.

"Fairy tale..." by Helen K, Flickr

Recommended Alternatives (Or, a place to start)*

Books

- Andersen, Hans Christian. The Complete Stories. Trans. Jean Hersholt. London: British Library, 2005.

- Atwood, Margaret. Good Bones and Simple Murders. New York: Random House/Nan A. Talese, 2001.

- Carter, Angela. The Bloody Chamber. New York: Penguin, 1990.

- Cashorali, Peter. Fairy Tales: Traditional Stories Retold for Gay Men. San Francisco: Harper, 1997.

- Goldman, William. The Princess Bride. 25th Anniversary edition. New York: Ballantine, 1998.

- Tatar, Maria, ed. The Classic Fairy Tales. Norton Critical Editions. New York: W.W. Norton, 1998.

- Zipes, Jack. Don't Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England. New York: Routledge, 1986.

Web sites

- Fractured Fairy Tales lists texts organized for children, young adults, and adults.

- The Fractured Fairy Tale Project provides a glimpse of children's own revisions.

- For educational activities, see another site called Fractured Fairy Tales.

Movies

- The Little Mermaid. Dir. Tim Reid. Sterling Entertainment Group, 1979.

- The Little Mermaid. By Hans Christen Andersen and Jack Olesker. Dir. Masakazu Higuchi and Chinami Namba. Golden Films, 1993.

- The Secret of Roan Inish. By Rosalie K. Fry. Dir. John Sayles. Perf. Eileen Colgan and Mick Lally. Jones Entertainment, 1994.

- Splash. Dir. Ron Howard. Screenplay by Brian Grazer and Bruce Jay Friedman. Perf. Tom Hanks and Daryll Hannah. Touchstone, 1984.

*By that, I mean I recommend checking these out yourself before deciding whether to let the kids!

Kate Comer is a PhD student in rhetoric, composition, and literacy studies at The Ohio State University and a founding editor of Harlot.

This work is licensed under Harlot's Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License.