I can be a rather skeptical reader — but sometimes more toward readers than authors.

The Shoemaker's Holiday by Thomas Dekker (1599)

Yup, the readers. You’re probably wondering how this works considering reading leaves no mark on a book, but sometimes these efforts are, sadly, not so invisible after all. Oh, you know who I’m talking about: those godless creatures who mark up library books! [crackle of thunder here]

I remember the first time I bought a heavily used book for a graduate class. I had taken so long to pick up the play, Thomas Dekker’s 1599 The Shoemaker’s Holiday, that all that was left was a battered copy with more lines highlighted than not. I had the hardest time with that book. I’m usually pretty good (or at least I used to be) at remembering where to find particular passages, but my reputation was seriously damaged with this episode. I could hardly recall where anything was located because I was thrown off by visual markers that, to me, meant nothing and only convoluted how I understood the play. I had no mental pictures of those pages.

It was then that I first began judging these invisible readers by how they mark up a book. After the first few pages, if a reader has highlighted what I think is fairly commonsensical, they get thumbs down, and I proceed through the rest of the book skipping any portions highlighted with that same pen. Or, if a person highlights what I would probably notice and shows herself to be fairly consistent about catching the good stuff, then I’ll come to pay more attention to the brightly yellowed portions of the book.

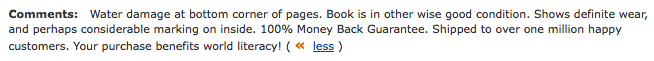

In recent years, I’ve been making heavy use of online booksellers to get a hold of what I need. When possible, I always buy new books, but if they are excessively expensive I’ll go for a used book and pay good attention to the descriptions booksellers give of their inventory. The only problem is many online booksellers have taken to writing almost no description of the book they’re selling. Instead they offer this kind of uselessness:

![]()

And then there are more comical instances like this:

Perhaps considerable?! I don’t know what that means — nor how my purchase benefits world literacy when I’m already quite literate, if I do say so myself — but it makes me think how cool it would be if booksellers could explain whether the markings are smart, uninformed, or some other variety. Not that I’d believe them, though. But it would be amusing.

I already own a copy of the book this last comment is on. I’m no stranger to highlighting, but I only do so when a book is particularly important to my work and when I expect to own that book for a long time to come. I’ve happily highlighted this copy because I expect it’ll remain mine, but it definitely makes me think about the lifecycle of highlighting. The next time I read this book, I’ll be more informed than the first time or the second or the third time through, so I won’t need nearly as many passages highlighted. Funny, isn’t it, how highlighting and leaving notes becomes a record of your intellectual status at the time of your reading?

These days I always highlight for a particular purpose. And it’s possible that neither I nor anyone else will ever match that exact purpose again. With time being a luxury I don’t have these days, I read for particular types of information rather than to piece together the trajectory of a book. It makes me think I’ll be (actually, I probably already am) one of those people who when asked to lend a book quickly shuffles through the pages first to see if there are any stupid comments that might ruin my credibility. Because I, too, will be judged. Alas.