A few days ago I posted some off the cuff, rather glib remarks about President Bush’s response to having a shoe thrown at him, at the very end of which I note Bush’s acknowledgment of protest as distinctly different than, say, Nixon’s. Well, today I’m revisiting a really stellar article by Jodi Dean, Queen of I Cite, a blog that covers political theory the likes of Agamben, Foucault, Zizek, and so on, which brings up the topic in a more serious light; so I’d like to follow up on my post with a quote from her article, “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics,” from Digital Media and Democracy:

Even when the White House acknowledged the massive worldwide demonstrations of February 15, 2003, Bush simply reiterated the fact that a message was out there, circulating–the protestors had the right to express their opinions. He didn’t actually respond to their message. He didn’t treat the words and actions of the protestors as sending a message to him to which he was in some sense obligated to respond. Rather, he acknowledged that there existed views different from his own. There were his views and there were other views; all had the right to exist, to be expressed–but that in now way meant, or so Bush made it seem, that these views were involved with each other. So, despite the terabytes of commentary and information, there wasn’t exactly a debate over the war.

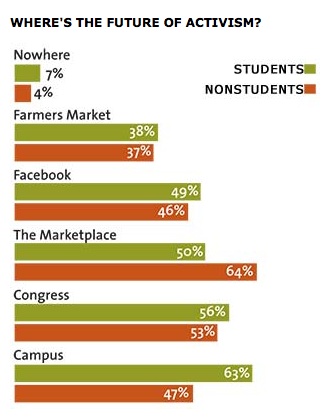

Dean goes on to make a persuasive case for the separation of a politics that is the simple circulation of content (websites, TV pundits, blogs, RSS feeds, listservs, and so on) and the politics of the institution (activities of lawmakers and bureaucrats). Today, she argues, these two politics operate almost entirely independent of each other. Sure, we’d like to think the circulation of content impacts the actual decision making . . . but it doesn’t. However, it does keep us busy.

I’ll end with one of her juicier claims:

The proliferation, distribution, acceleration, and intensification of communicative access and opportunity, far from enhancing democratic governance or resistance, results in precisely the opposite, the postpolitical formation of communicative capitalism.

There’s a distinct chance I’ll be posting on this over at Candid Candidacy if any of you are enticed by these ideas.