A neo-Aristotelian analysis of Obama’s State of the Union speech might focus on how he builds credibility after a mid-term election gave significant traction to a Republican agenda. A Lakoffian critique would look at which dominant metaphors work to shape the framing of other issues, like how “the race to educate our kids,” “this is our sputnik moment,” and the theme of “winning the future” all contribute to a framework of competition. A Burkean cluster approach would organize key terms around frequency and intensity and extract an analysis from there.

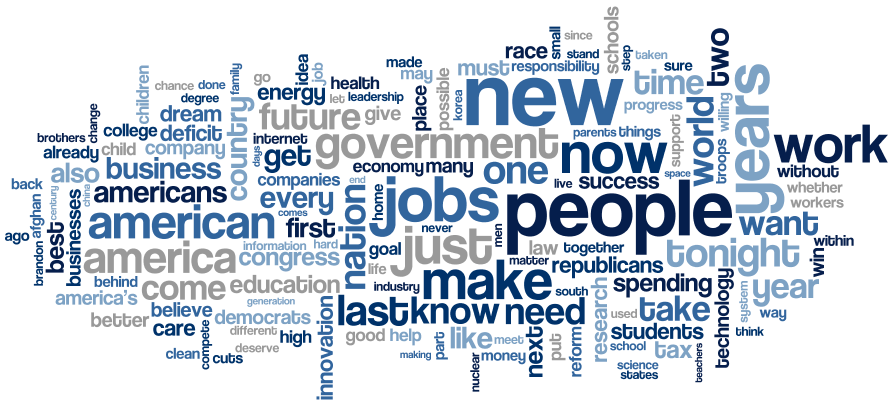

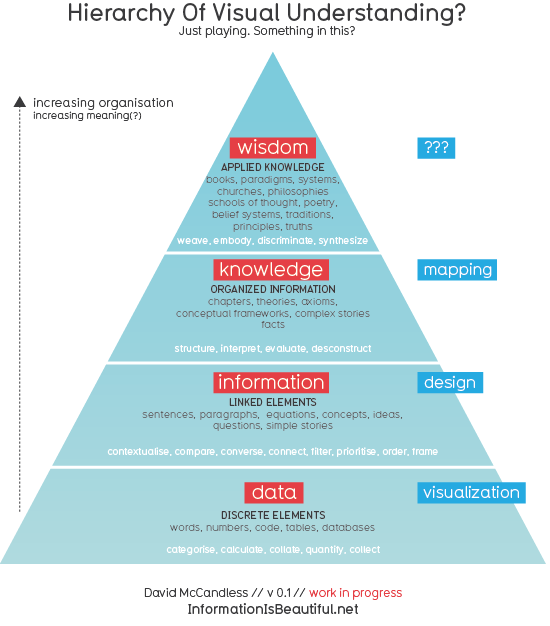

Here’s what that would look like with regards to frequency:

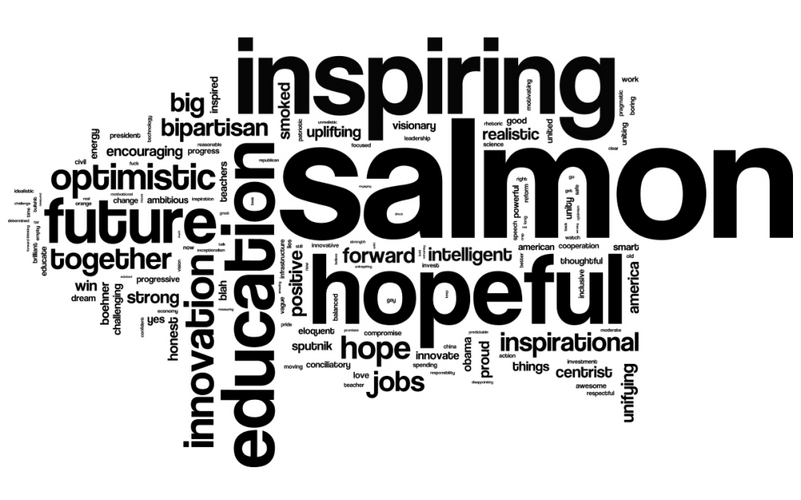

But what about intensity? NPR did some reader-response analysis, asking over 4,000 people to describe the speech in 3 words. Here are the surprising results:

Um, I for one did not see that coming. Granted, there are very few jokes made in State of the Union speeches, so one could argue that those that do make it in are bound to stand out. But nevertheless, I find this surprising.

What can we glean from this data about the impact of Obama’s speech? What can we suggest about the role of sarcasm in this situation? What rhetorical methods do we have which can account for this anomaly?

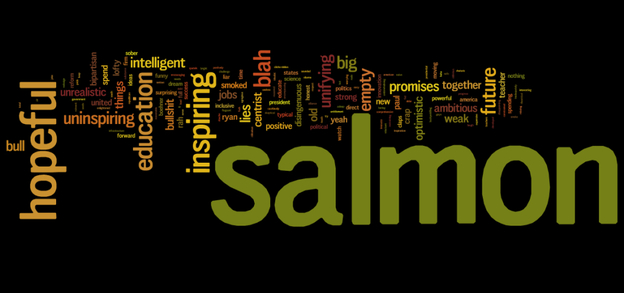

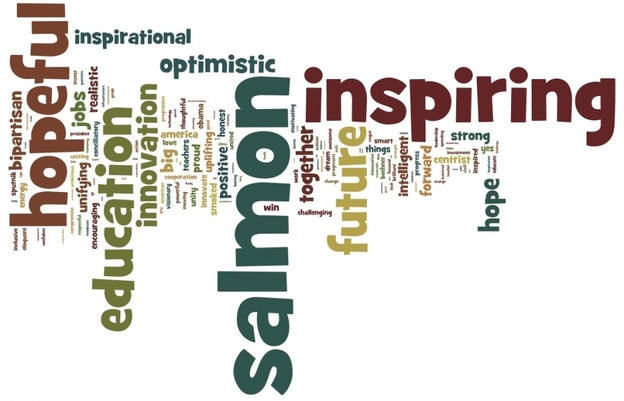

To make matters perhaps even more interesting, here is the same data broken down into party-affiliations:

Republicans

Democrats

I’ll be curious to hear some of your responses to this data.

————————————————————————

** I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that Obama missed an opportunity to point out the plight of salmon. All five species of Pacific salmon are endangered: Chinook, Chum, Coho, Pink, and Sockeye. It was not long ago at all that this now-endangered species thrived. From Derrick Jensen, a staunch defender of salmon and all wild life:

At one time the Columbia River Basin was home to the greatest runs of salmon on earth. In 1839 Elkanah Walker wrote in his diary, “It is astonishing the number of salmon which ascend the Columbia yearly and the quantity taken by the Indians. . . .” He continued, “It is an interesting sight to see them pass a rapid. The number was so great that there were hundreds constantly out of the water.” In 1930, Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene Press wrote, “Millions of chinook salmon today lashed into whiteness the waters of northwest streams as they battled thru the rapids. . . .” The article went on to say that “the scene is the same in every northwest river.” Spokane, Washington’s Spokesman-Review noted that at Kettle Falls, “the silver horde was attacking the falls at a rate of from 400 to 600 an hour.”

Now the salmon are gone. To serve commerce our culture dammed the rivers of the Columbia River Basin. People at the time–beginning in the 1930s–knew dams would destroy salmon. Local groups and individuals–including those who knew salmon most intimately, the Indians–fought against the federal government and the river industries, but dams were built and now the fight is becoming even more desperate, as nine out of ten major salmon species in the Northwest and California are extinct or on the verge.