“Language—in any case, language in the Indo-European cultures—has always given birth to two kinds of suspicions:

- First of all, the suspicion that language does not mean exactly what it says. The meaning that one grasps, and that is immediately manifest, is perhaps in reality only a lesser meaning that protects, confines, and yet in spite of everything transmits another meaning, the latter one being at once the stronger meaning and the ‘underlying’ meaning.

- On the other hand, language gives birth to this other suspicion: It exceeds its merely verbal form in some way, and there are indeed other things in the world which speak and which are not language. After all, it could that nature, the sea, the rustling of trees, animals, faces, masks, crossed swords, all of these speak; perhaps there is a language that articulate itself in a manner that is not verbal.

These two suspicions, which one sees already appearing with the Greeks, have not disappeared, and they are still with us, since we have once again begun to believe, specifically since the nineteenth century, that mute gestures, that illnesses, that all the tumult around us can also speak; and more than ever we are listening in on all this possible language, trying to intercept, beneath the words, a discourse that would be essential.”

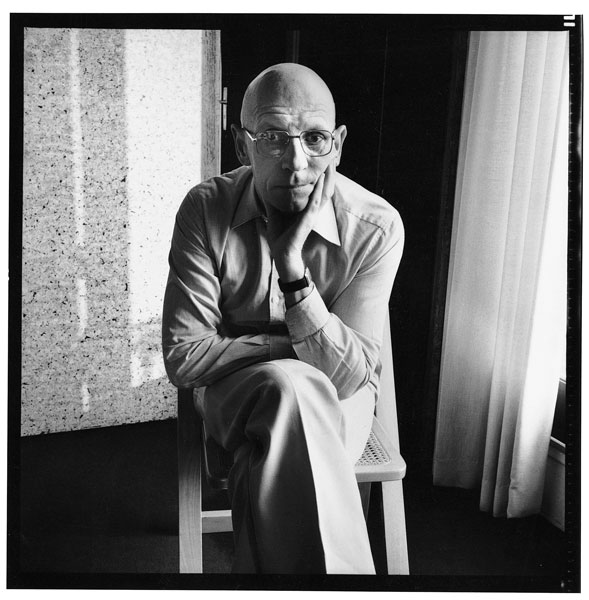

+ Michel Foucault, excerpted from the essay, “Nietzsche, Freud, Marx”