I have only fuzzy memories of the late nineties, but I can clearly remember finding out way back in 1999 that Jon Stewart was taking over for Craig Kilborn, and actually thinking…this guy’ll never be able to replace Craig. And he didn’t. Instead, he reinvented The Daily Show as many of us have known it for the last sixteen years: a pop-culture platform for reframing in humor what many of us experienced as the––insert your own hyperbolic adjective here––of coming to adulthood against the backdrop of the Bush years, 9/11, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the economic meltdown of 2008. For me, The Daily Show, and later The Colbert Report, operated as cathartic performance art that challenged traditional notions of the real/fake binary.

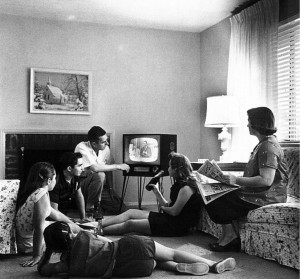

When I was growing up, traditional news programs were a staple in my family. I have clear synesthetic memories of the smell of breakfast cooking as my Dad got ready for work, my brother and I in pajamas, the family conversation overlaying the familiar babble of the local news station as it played in background. As a child, I remember trusting those talking heads because they seemed so official, so possessed of “capital T” Truth.

When I was growing up, traditional news programs were a staple in my family. I have clear synesthetic memories of the smell of breakfast cooking as my Dad got ready for work, my brother and I in pajamas, the family conversation overlaying the familiar babble of the local news station as it played in background. As a child, I remember trusting those talking heads because they seemed so official, so possessed of “capital T” Truth.

After the clusterf*ck that was the 2000 election (the first I was old enough to vote in), I found myself increasingly kerfuffled every time I tuned in to traditional news outlets. The Daily Show represented a way to stay connected to current political information without disintegrating into a puddle of panic. As time marched on, and the aggravation of the 2000 election was overshadowed by the horror of 9/11 and the ensuing madness of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Stewart’s, and later Colbert’s, humor transmuted the shock and sorrow of those difficult years. I found myself trusting The Daily Show in a way that I could no longer trust other sources of news, and I was not alone. Many of my friends had turned away from traditional news outlets, preferring to get their information from the Internet, each other, and Comedy Central.

The trust that my generation has placed in Stewart and Colbert has evoked nervousness and ire from both sides of the political spectrum. And while it’s easy to accuse The Daily Show and The Colbert Report of diffusing activist outrage and fizzling real feelings of political discontent, I have to (sheepishly) admit that the majority of my “outrage” tends to manifest as paralyzing terror. So, while perhaps some people’s political momentum was arrested, The Daily Show and Colbert Report kept me in the world, kept me in the pipeline of information, and forced me to laugh at the insanity instead of hide from it. Is this the most effective strategy for political change? Probably not. Has it kept me involved in a certain way, yeah.

In their Salon article “The day Jon Stewart quit: Why ‘The Daily Show‘ isn’t the satire America needs,” Jamie Kilstein and Allison Kilkenny come down hard on Stewart and Colbert’s 2010 “Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear” which brought together folks who “don’t like shouting” for a spectacle of “reasonableness.” I saw the rally as a type of performance art designed to draw attention to the all-too-invisible subjectivity at work in the red/blue binary. Kilstein and Kilkenny completely miss this point, instead adhering adamantly to the binary, stating that the “division’ [Stewart] dismisses is literally the only fight that matters.” If the division between red and blue is all that matters, then each of us becomes subject to the binary-driven political narrative, created in its image. Rather than simply satire, or a rejection of activism, the rally strove to disrupt the seeming solidness of a system that gives two pre-defined options and calls it a “choice.”

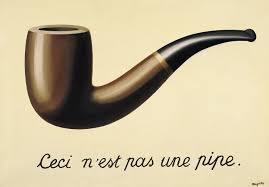

It’s too easy to pick apart these shows, to blast them for what they did or didn’t do politically. Or to compare them to more politically subversive comedians from the past. But The Daily Show and Colbert Report have done more than just amuse and distract, they’ve drawn attention to the absurdity of the political and media simulacra that’s been right in front of our faces all along. Like Magritte’s “Treachery of Images” forces the issue of representation vs. reality, just raising the “is it a ‘fake’ or is it a ‘real” news program question makes visible that all politics and media are a construction (and, if you want to go down a rabbit hole, that all reality is itself a construction).

If anything, complicating the real/fake binary provides a productive space for challenging established structures. By replicating and adapting the genre conventions of the “trusted” News program, and remixing it with absurdism, humor, and cartharsis, The Daily Show and The Colbert Report are neither real nor fake, neither humor nor news, but something that calls attention to the power of both.

As a rhetorical appeal, humor can be seen as a form of pathos, an emotional appeal. Make someone laugh, and they’re more likely to like you, and therefore more likely to be persuaded by you. But that’s too simplistic a notion for the role that Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert have played in many of our lives. Rather, it seems that their humor was enacting an alchemical process of transmutation; as we sat with our sorrow, frustration, and anger, horrified by the unfolding of events that we felt little power to halt or effect, humor cathartically transmuted those feelings, providing instead a way to feel interconnected, and, through the process of posing the question: is it real or fake? granted us agency through awareness of the simulacra.

Though it may have couched itself as a “fake” news show, The Daily Show has provided a very real space for transmuting a generation’s frustration, anger, and disappointment. Where we have felt disenfranchised in many areas of our lives, the sheer force of Stewart and Colbert’s ability to get folks to act en masse has been vicariously thrilling during times when a lot of people have felt unheard. Stewart and Colbert have shown us that smart and geeky can be powerful, that wit can win, that the pen is mightier than the sword. Or at least, reminded us of these things for an hour a day, four days a week.