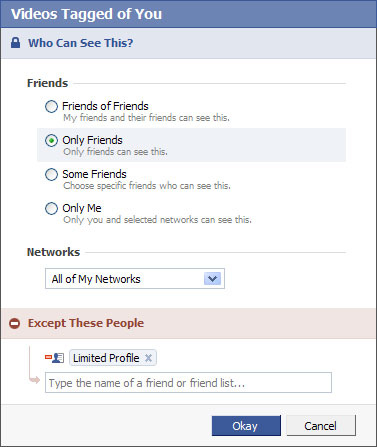

CNN Tech brings us “Defriending can bruise your ‘digital ego,'” which is all about just that. A lovely, succinct title, don’t you think? With much of our communication moving to digital formats, our interactions seem to take on varying moves of importance. A coworker who talks to you on the job, but who refuses to accept a friend request can be squishy territory. There’s no question that these digital devices change the way we communicate, but it makes me wonder if it changes the nature of our relationships.

A local magazine, UWeekly, wrote an article recently about “Text Dating–” the phenomenon of getting to know a person through text first before having much real world interaction with them (which I find kinda funny–most people would have already met in person in order to exchange numbers, no?). According to the article, this makes it more difficult for people to know how they should act once they are in real world contact. Ain’t that interesting?

I’ve often wondered if all this texting is similar to old time letters in any way. A fair amount of letters that were written during the civil war, for example, had such tenderness. I mean, yeah, they were soldiers who talked about people dying too, but the feeling they displayed for the recipient of the letter was heartfelt. Here’s the thing, though. They almost had to be forward in their feelings, because there weren’t other forms of accessible communication–they couldn’t just call, text, email, facebook, etc. Being forthright in their written communication was necessary to maintaining their relationships. Texting is not always a forthright thing (and sometimes it’s too forthright). So, attempting to create a relationship based on digital communication can be a hard thing to do. Perhaps it’s because it hasn’t been done to the same degree that other forms have. Maybe there is a reason why we choose that form–it’s distancing, but still revealing.

By choosing this digital form, it’s as if people learn a lot of facts about each other–schools attended, parties attended, favorite books, etc–but without knowing a person’s soul. Oooo, deep moment for today, right? But really, can you really get to know a person via the digital? If you can’t interact with that person and see how they shut the fridge door with their foot or chew on their pen caps, then can you be clued in to all that necessary non-verbal communication? Plus, do these digital digs give us the opportunity to always present our best (or worse) selves? Does that mean that a person feels connected to another or to the representation that that person gives?

Technology has a significance in our lives. When someone defriends you, it stings. It would still sting to the most selfless person ever, but where is the line between using technology as a tool for staying connected and expecting technology to do all the work for us?